I’d like to take a moment here at the top to note a great loss to the Ohio State History Department. Earlier this week, Dr. John Guilmartin passed away. Dr. G taught early modern and military history at Ohio State, and covered a lot of material in his work. In addition to classic works on galley warfare in the Mediterranean in the 16th Century, he produced good work on ancient warfare, the Vietnam War, and the intersection of technology and warfare- particularly in understanding black powder.

Of course, professoring was a second career for Dr. G. Before, he flew combat rescue helos. After earning his Ph.D, he flew the Saigon Evacuation. Before graduate school, he flew in support of Operation Rolling Thunder, earning two Silver Stars in his tour for, effectively, rescuing downed pilots that had parachuted into areas too hot for other rescue flights to attempt the rescue. I think it is fitting to say that there are many people alive today who wouldn’t be, if he weren’t there for them.

The Second League of Armed Neutrality

Ultimately, the Battle of Copenhagen was a round in a long standing, well armed debate about shipping rights, and who owned cargos aboard ships while at sea. Taking enemy ships and their cargoes as prizes, and then selling them for profit, has been part of war at sea for as long as there have been ships. Of course, there was little to distinguish prize taking at war from out and out piracy, so anyone involved in the business risked a pirate’s fate if caught. However, in the Middle Ages, as many Western European kingdoms adopted Justinian’s Codex as the basis for their laws, the also began adopting, and creating, their own maritime laws. The first serious maritime court in the west, based in Barcelona, established a series of laws and decisions that became known as the Consolat de Mar. The first codex of laws and court decisions came out of the Consolat in 1494, and became the basis for the Customs of the Sea. A the first Prize Court in the Western world, the Consolat established the principle that, if neutral ships carried the goods of a belligerent, the other side could stop that ship and seize those goods as prizes. However, if a neutral merchant shipped his goods on enemy ships, then those goods could not be taken as prizes.

In the 1600s, however, the Dutch Republic, at war with Spain, contested the idea that neutral ships could be stopped at sea and searched. Hugo Grotius, the noted legal scholar, argued that neutral ships could not be stopped, nor their goods seized. However, any goods on an enemy ship could be taken as prizes, as could contraband of war- arms, powder and shot. As this went against international norms, the Dutch had to negotiate this idea into a number of treaties with other nations. However, as the Dutch were the most effective and profitable shippers in the world, other countries wanted to establish trading relations with them, and were willing to abide by Dutch rules. However, the British. The Dutch had to use force to get British to follow these principles, including fighting several wars against the English in the 1600s. However, the British only respected Dutch neutral shipping rights, and applied the Consolat rules to everyone else.

During the American War of Independence, the British abrogated their treaties with the Dutch. The French and Americans, needing to move cargos across the Atlantic, used the Dutch to move various cargoes around to avoid British blockades and the Royal Navy. However, on New Year’s Eve, 1779, a British squadron fell on a Dutch convoy, and demanded a physical inspection of the ships, rather than the usual manifest check. The Dutch commander refused, some shots were exchanged, and the British took the entire convoy as a prize. Shocked by this action, and fearing that Russian ships would be next, Catherine the Great declared her support for the rights of neutral shipping at sea. She also announced that she rejected the idea of blockades of entire coasts, only specific ports, and only by ships on close blockade of those ports. (International law recognized taking as blockade runners as prizes.) She drew the Baltic powers, Denmark and Sweden, into a League of Armed Neutrality, which promised military action against anyone who violated their shipping. Austria, Prussia, Portugal, the Ottoman Empire and the Kingdom of Two Sicilies eventually joined the League. The French, Spanish and Americans couldn’t join the League as belligerents, but supported Free Ships, Free Goods. After the War, the French and Americans continued to try and spread the principle as a new basis for the law of prizes.

After leaving the Second Coalition in 1800, Paul I of Russia decided to revive the League, in order to put pressure on the British to seek peace, and to protect the valuable Baltic trade from British interference. The Danes, Prussians and Swedes quickly joined, and, later, the French signed treaties with the members of the Second League, promising to respect their rights, and convinced the Americans to do the same. However, the US decided against joining the League directly.

The Battle of Copenhagen

The British saw the League as a threat to the British. The League commanded an impressive fleet, for the first part- 123 ships of the line. Even if the League refused to declare war on the British, an embargo would be nearly as bad. British shipping relied on the Baltic trade for naval stores. All British ships used tall trees harvested from Sweden and Finland for their masts, and relied on Sweden and Norway for supplies of pitch and turpentine.

After the Treaty of Luneville, the British stood alone against the French. They saw the League as a move towards a more pro-French attitude amongst the members, and decided to drive the League apart by force. In early 1801, the British put together a squadron under Admiral Hyde Parker. Parker was ordered to break apart the League by first convincing the Danes- by a show of force or actual violence- to leave the League, and then do the same to the Russians. He left in March, 1801, so that he could reach Copenhagen before the ice thawed around the Russian fleet. Parker decided to move cautiously, which aggravated his second in command, Horatio Nelson. Nelson argued that Parker should bypass the Danes entirely and attack the Russians, burning their fleet while it remained frozen in. However, Parker decided to act in late March, after receiving word that the Danes had rejected a British ultimatum to leave the League.

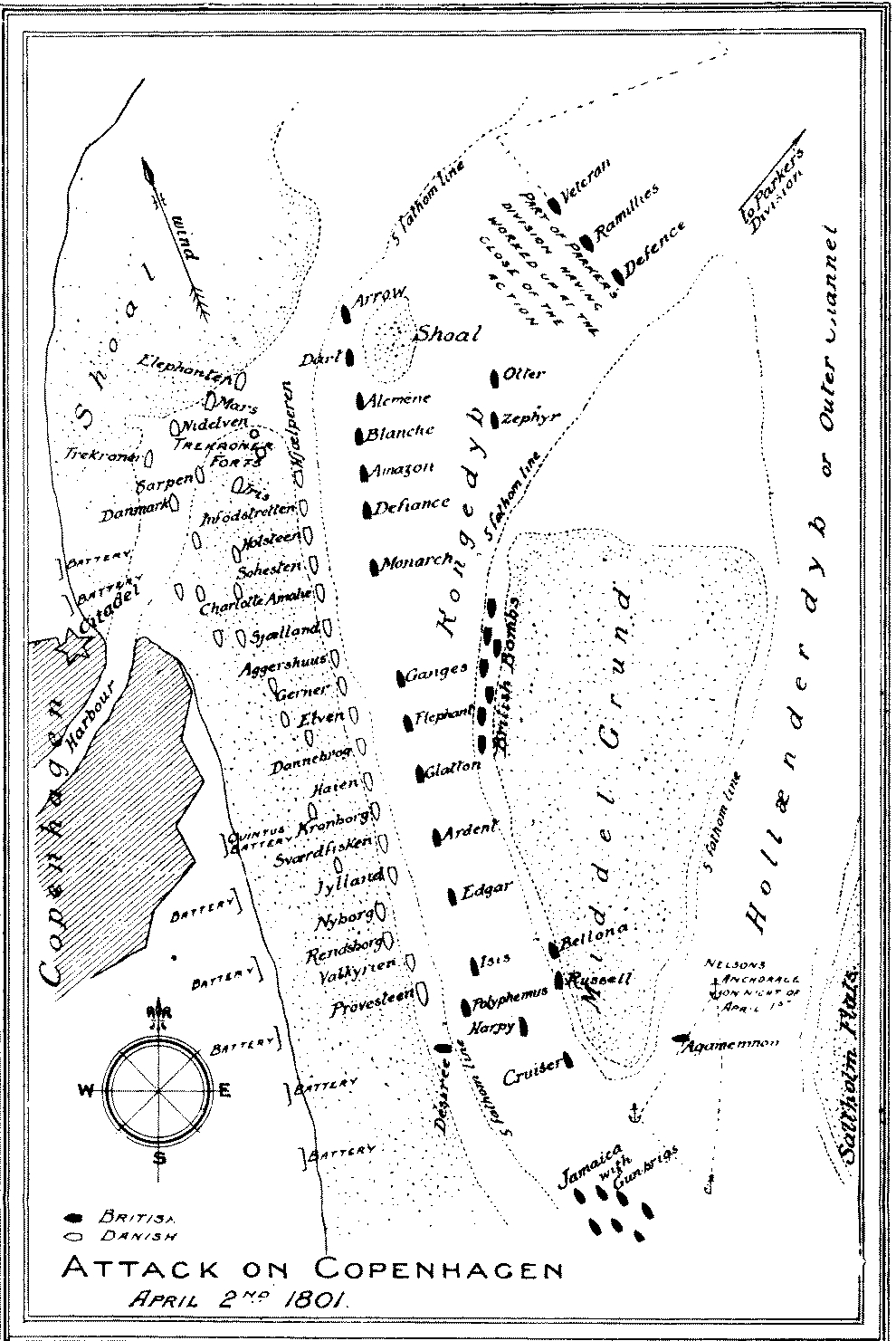

Copenhagen lies on an island in the Baltic, surrounded by smaller islands, shoals and straits. To enforce his demands, Parker would need to put the city itself under the guns of his fleet. This wouldn’t exactly be easy. The only route to the inner harbor of the city lay on the King’s Channel, a narrow band of shallow water between two sand banks. The city, and its approaches, were well guarded with fortresses in peacetime, and the Danish fleet was not a small one, compared to the British squadron.

The Danish Commander, Olifert Fisher, was not ready for an outright battle at sea. So, rather than face the British there, he decided to face them off the coast of Copenhagen. He drew up seven of his ships of the line, along with several hulks and frigates, into a line south of the city. At the head of his line lay the massive Tre Kroner fortress, with smaller batteries on the shore down the line. He also placed several ships in the mouth of the channel into Copenhagen itself, and pulled up all the bouys and arrested all the pilots in the area. All in all, he had 9 of the line and 20 other ships, which he anchored as floating batteries.

Parker ordered Nelson to lead the attack itself. He gave him all the smaller ships of the line, with the lightest draft- a total of 12. He also gave him five frigates, seven brigs, and six bomb ketches. The bomb ketches were armed with mortars, and could fire over the British line. Nelson decided his best chance lay in attacking the southern part of the Danish line, the furthest from the Tre Kroner fortress and the hardest to reinforce. With the southern part of the line gone, he could bring up the bomb ketches and bombard the city. To do this, he ordered his ships of the line to sail into the King’s Channel. As the lead ship came alongside the southernmost ship in the Danish line, it would drop anchor, and the fleet would pass by. The rest of the line would drop off in succession in that manner, until it was all deployed. The Brigs would form a line along the southern end of the Danish line, while the frigates would attack the northern end of the line and Tre Kroner. The ketches would anchor on the far side of the British line, and bombard the Danes by firing over the British ships.

On April 2nd, the morning breeze proved favorable to Nelson’s plan, and he sailed into Copenhagen. However, the first three ships of his line ran aground on the Middle Bank, forcing him to swing closer to the Danish line than he had hoped. At 1000, the Danish batteries opened up, and, by 11:30, both sides were engaged in an all out battle, exchanging fire at a murderous rate. Both sides, anchored and motionless, could only slug it out, and cannonballs ripped through ships, masts, and men.

At 1330, Parker had no real word of the progress of the battle. He was concerned that the battle was going poorly for Nelson. However, Nelson could not break off the action even if it were- to do so would mean a death sentence. Parker maneuvered his flagship into a spot where only Nelson could see it, and raised the signal for a retreat, knowing if the battle was going poorly, Nelson would leave- but if it were going well, he would just pretend to not see it. Nelson’s crew alerted him to the signal. However, Nelson had lost his right eye in a ground battle in Corsica in 1793. He held his glass to his blind eye, said he saw nothing, and continued the fight.

The Battle, however, was going Nelson’s way. Superior British gunnery allowed them to make many more hits than the Danes, and to fire more quickly. As Danish crews suffered losses, men from the shore batteries sailed to replace them, eventually silencing the batteries as well. As Dutch ships struck their colors or retreated, the British ships moved up the line, closer and closer to Copenhagen. By 1400, most of the Danish fleet had fallen slient. However, even as the Danes surrendered, some of their crews continued to fight. Nelson decided he had had enough, and sent an envoy ashore. His envoy told Crown Prince Federick, the Danish Regent, that either he had to surrender, or else Nelson would burn the batteries and their crews alive, be unable to treat the Danish wounded, and would have to bombard the city and kill many of its citizens.

This was something of a bluff. In addition to the ships he had lost aground, most of Nelson’s command was heavily damaged, and not in tremendous shape to keep fighting. His frigates had been unable to deal with Tre Kroner, and had withdrawn. The fortress was fully manned, and supported by several ships untouched in the fighting. In fact, several British ships, effectively adrift, were being pushed into range of the guns. However, the threat to the city itself, and to the wounded and men in the batteries, could not be ignored. Frederick agreed to a cease fire to carry off the wounded and to prepare for further negotiations.

The Danes agreed to an armistice of 14 weeks, during which Nelson and Parker could repair their fleet in Copenhagen. However, the Danes refused to give on the issue of free trade, nor on leaving the League permanently. Events in Russia, however, made this rather irrelevant. A conspiracy of Russian officers succeeded in assassinating Tsar Paul I, and replacing him with his son, Alexander I. Alexander swiftly reversed his father’s anti-British policy, and began organizing an alliance that might oppose France, ending the Second League of Armed Neutrality.

The Peace of Amiens

Since 1799, Napoleon had tried to negotiate some sort of peace with Britain. However, Pitt the Younger, the Prime Minister, had made the destruction of the French Republic the cornerstone of his foreign policy, and to this end, had levied taxes- including an income tax- and disrupted trade, causing the price of grain to rise. However, it was the issue of Catholic Emancipation that brought Pitt’s resignation, and the next PM, Henry Addington, faced pressure to end an unpopular war. The French and British settled on terms in October, 1801, and formal peace came in March, 1802. In the treaty, Britain agreed to recognize the French Republic, the Batavian Republic, as well as the Republics of northern Italy and in Switzerland. The British further agreed to return the Cape Colony in South Africa to the Batavian Republic, as well as the Dutch West Indies. They agreed to return Trinidad, Minorca and Ceylon to Spain, and Malta to the Knights Hospitaliers, who were to be reformed. In return, the French agreed to move out of southern Italy, and to pay off the House of Orange for their losses in the Netherlands.

The Peace would be short lived. In 1802, Napoleon accepted the Presidency of the Piedomontese Republic, in violation of Luneville and Amiens. He sent in troops to annex the Cisapline Republic, and to enforce order in the Helvetian Republic. When Britain objected to these violations of various treaties, Napoleon informed them that Britain stood separate from the Continent, and had no rights to interfere there. He also demanded that the British censor the anti-French press, and expel his enemies that were hiding out in Britain, which insulted British sovereignty. However, when Napoleon decided to send and expedition to end the Haitian Revolution, they decided that Napoleon had long term plans to isolate, then destroy, Britain.

In response to these actions, the British refused to turn over Malta or the Cape Colony, and further refused to withdraw from Egypt. In early 1803, the two sides attempted to negotiate a solution, but, frankly, neither side really wanted peace at this point. On May 17th, 1803, the Royal Navy put to sea, seizing millions of pounds of French and Dutch cargos, and on May 18th, Britain declared war on France, restarting the war. Both France and Britain began furious diplomatic efforts prepare for the coming War of the Third Coalition.

If you enjoy military history on 11W, feel free to check out the archive here, and comment below.