So, I'd like to apologize a bit for the late arrival, and truncated nature of, this post. I was working on this earlier, only to have my computer give me the finger and dump it. So, in an effort to get something going, I'm going to focus on the battle itself, and the Swedish tactical method, and less on the campaign leading up to the battle than I did before my computer ganked my post.

This week, we'll build on our discussion of the Battle of Rocroi, last week, to discuss the Battle of Breitenfeld. Rocroi was something of a standard battle for the era, with two similar armies led by two able commanders slugging it out over a couple of hills with one side winning by gaining a flank. Breitenfeld, however, is a masterclass of a battle, fought between two of the great commanders of the age: Gustavus Adolphus, King of Sweden, and Count Tilly. The battle solidified Gustavus' reputation as a military genius. However, it didn't settle a damn thing in the war- despite their defeat, the Imperials rallied and put together another army quickly, and neither Tilly nor Gustavus would survive the fighting in 1632.

If you're new to the series, or need a reminder of the course of the 30 Years War or the tactics of the Spanish (and Imperial) Tercios, please refer back to last week's discussion on Rocroi here:

http://www.elevenwarriors.com/forum/anything-else/2015/11/62488/the-11w-...

Gustavus' Tactics:

During the 1620s, Gustavus fought a series of wars in Poland to claim control of various areas he claimed in the Kingdom of Poland. The Poles mostly used tercio style tactics, which Gustavus' forces struggled to fight against. To find a way to counter this Gustavus studied the tactics used by the Dutch in the late 1500s to fight the Spanish tercios with a fair bit of success.

As a quick reminder, the tercio is an infantry formation, with a mix of different arms that worked together to protect and supplement each other's strengths to create a formation where the whole was larger than the sum of its parts. At the center of the formation was a deep block of pikemen and swordsmen, while musketeers both guarded the flanks of the formation and formed blocks of musketeers at the corners. These musketeers rotated their fire to deliver a light, but steady, fire into the enemy. It looked something like this:

This is a very balanced formation- it can fight other pike blocks or cavalry units, it can deliver fire in any direction, protects its own flanks, and manuvers well when the troops are well trained. On the defense, it has vast reserves of men. On the attack, the depth of the pike formations provided mass to carry the attacks home. Overall, this formation won dozens of battles from 1500 to 1700.

To counter this, Gustavus decided to give up depth of formation for firepower. Instead of deploying his men into formations 20 or so ranks deep, he arranged them into formations six ranks deep. This concentrated firepower to the front, putting more men on the firing line, and more pikes into contact when the infantry got in close. While this concentrated fighting power, it meant giving up the depths of reserves in the defense, and the mass of columns in the attack, compared to the tercio. It would have looked something like this:

In addition to using the rolling fire tactics invented by the Dutch and adopted by the Spanish, where a rank would fire, then retreat to the rear of the formation. This kept up a steady fire, but, the Swedish formation delivered about double the number of shots per rank. Additionally, Gustavus trained his men in delivering a volley of fire. When the distance between formations closed, usually around 30 yards, Swedish musketeers would squish up into three ranks, the first kneeling, the second stooping, and the third standing, and deliver a simultaneous fire. This fire would smash into the enemy pike formations, causing the men in the first ranks to fall, tripping up the men behind them. As the enemy formation fell into chaos, the Swedish pikes would take advantage and close. At least, that was the theory.

As a further focus on firepower, Gustavus reduced the number of field guns in his army for smaller cannon- one or two per regiment- to deliver close range cannon support of the infantry. Most of his field artillery came from his allies.

Because of a shortage of skilled gunsmiths in Sweden, Swedish cavalry lacked large numbers of wheelock pistols, of the kind used by Spanish and Imperials to deliver fire before making attacks. To make up for this, Swedish horse concentrated on full speed charges with swords to close with the enemy and destroy them- or get wiped out themselves. To further support his horse, Gustavus also deployed groups of musketeers with them, who could fire when they charged.

The Battle of Breitenfeld

In 1630, at the behest of Cardinal Richelieu, the Prime Minister of France, Gustavus landed an army in northern Germany, while Tilly's Imperial Army was actually in Italy, settling the issue of who would be the Duke of Mantua. Over the course of 1630, Gustavus built up a base of support and supply in northern Germany, either persuading or forcing local nobles to support him. Meanwhile, Tilly's army took Mantua, and then turned north. In the spring of 1631, the two armies began to close with each other in Saxony, in southeastern Germany. Saxony was good campaigning country- it was one the few places that hadn't be completely ravaged by the war, and still had enough food to support two big armies. Over the course of August, the two armies drew up their detachments in preparation for a major battle.

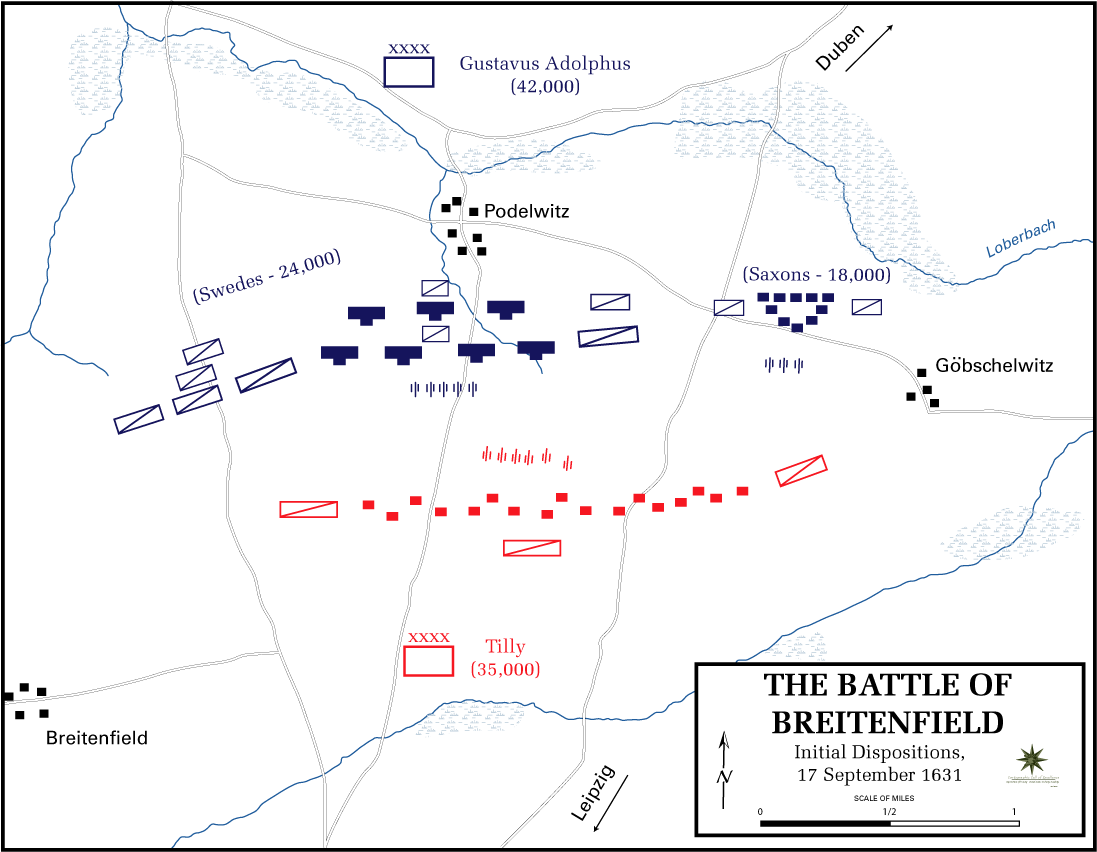

Gustavus, on paper, had the larger army. He brought 42,000 men to the field, 29,000 infantry and 13,000 cavalry, compared to Tilly's 35,000 men, 26,000 infantry and 9,000 cavalry. However, Gustavus' force included a force of 18,000 or so poorly trained and equipped German militias, who lacked an understanding of the Swedish methods, had few firearms, and poor leadership and morale. Tilly's army had some poor troops, but the bulk of the army was either veteran mercenaries or troops who had fought with Tilly in Italy, if not even longer. Tilly also had an advantage in heavy field guns, 24 to the 12 Swedish guns, though the Swedes had dozens of small guns with their infantry.

On September 7th, the two sides met on a field a few miles north of Leipzig. The battle was, essentially, a meeting engagement, with both sides coming together and mutually deciding on battle on the field . The field itself was largely devoid of significant terrain, consisting of fairly flat fields between two rivers and bordered by small towns. This was going to be a battle of skill- the skill of the generals, and the skill of the soldiers.

Over the course of the morning of the 7th, Tilly deployed his army into a fairly conventional arrangement. He balanced his cavalry evenly on his flanks, with his best horse held in reserve. His infantry went into the center, deployed in a standard checkerboard arrangement where they could protect each other. His guns went to the center of his line. Gustavus, however, adopted a different formation. He placed most of his cavalry on his right. From right to left, he then deployed his Swedish infantry into double lines, with the rest of the Swedish cavalry to their left. On his far left flank, he put the German militias, deployed into a kind of triangle of tercios, with their cavalry on their flanks. By noon, the forces arranged themselves like so:

The action opened with a two hour artillery duel. Despite having fewer guns, the Swedish artillerists proved to be quite skilled, and delivered a lot of fire into the Imperial center. Tilly decided, under the circumstances, to begin an attack. He targeted the weak point in the Swedish line, the Germany infantry, and attacked it with the horse on his right. The Saxon forces on that flank completely melted, running from the field under the withering fire from Imperial horsemen and the weight of their charges. However, on the other side of the field, the Imperial attack did not go nearly as well. The Imperial horse charged into the Swedish forces, only to face heavy fire from the musketeers deployed with the Swedish horse. This fire broke up the attacks, while the Swedish cavalry charged to drive back the Imperial horse, then retreat back to the shelter of their musketeers. The Imperial commander on the left, Pappenheim, made seven attacks, each one repulsed. After the seventh attack, the Swedish commander, Baner, launched an all out attack, closing with swords to finish Pappenheim's cavalry and force them from the field.

Tilly, seeing Gustavs' left flank in disarray and the Saxons in flight, decided to reinforce success. He marched his tercios in an oblique march to curl around and concentrate on the Swedish left, delivering the bulk of his infantry into Gustavus' veterans. To meet this attack, Gustavus ordered the second line of his infantry into battle, refusing his flank to stop the Imperial attack. Tercios are good at many things, but an oblique march across a field is not really their strong suit, and the Swedish infantry was able to shore up their flank before the Imperial infantry crushed down on it. Tilly's men began to organize a methodical assault on the Swedish position, resisted by the fierce fire of Gustavus' men, who manage to halt the initial advance and hold the position.

Meanwhile, on Tilly's left, Gustavus entered the fray personally, leading his personal guard of cavalry. He moved to reinforce Baner, and recalled his cavalry to keep it from pursuing Pappenheim's broken force from the field. He swung around the flank of his army, and moved to capture the Imperial artillery. Once he took control of these guns, he turned them on the Imperial infantry, catching them in a cross fire from Swedish artillery, captured imperial artillery, and Swedish infantry. The captured pieces enfiladed the entire Imperial attack, smashing across the entire army. Gustavus also carried his horse all the way around to the rear of the Imperial army, attacking it from behind. For the next few hours, Tilly, attempted to defend his army from the rear, facing murderous fire from the flanks, and attack into the right flank of the Swedish army. The Swedes held, but, as the day came to an end, the Imperial army began to fall apart slowly, then all of a sudden, it broke and ran.

The action on the field left 5,500 dead Swedes, and 7600 dead Imperial troops. However, the pursuit launched by Gustavus finished what the battle started. He captured 6,000 men on the field, and another 3,000 two weeks later. Another 7500 men called it quits for the Imperial side, and went home. By the time Tilly finished retreating, he only had about 5,000 men left to rebuild his army.

Gustavus' great victory did not end the war. Tilly pulled together 20,000 more men over the winter, and returned to the field in 1632. He would die that year at the Battle of Rain in the Spring of 1632, but his successor, Wallenstein, would kill Gustavus at the battle of Lutzen in the fall of 1632. The Protestant success at Breitenfeld would revitalize the Protestant League in the HRE, leading to a number of nobles joining the rebellion against the Emperor. However, the Swedish defeat at Lutzen just meant that the Imperial forces would have to spend the rest of the 1630s putting them back into place, before the French entered the war later that decade.

The battle did cause a reform of the tactics of the tercio, with more emphasis placed on being able to deploy more firepower to the front, and to make the formations easier to maneuver. Other forces, in the Netherlands, adopted a number of these tactics as well, making fighting even more sophisticated. This drive for more firepower led to the invention of the socket bayonet, and, by 1700, the abandonment of the pike as a serious infantry weapon. But, that's a topic for another era.

But, the battle did inspire this bitchin' painting:

And that's worth something.