Ohio State lands a commitment from five-star DE DJ Jacobs, 247Sports’ top-ranked prospect in the 2027 recruiting class.

Anyone remotely familiar with The Ohio State University is aware of the impact Wayne Woodrow Hayes left on the institution that employed him for nearly three decades.

Hayes led his teams to five national championships, 13 Big Ten titles, and over 200 victories while roaming the Scarlet and Gray sideline, building an elite program at a time when the sport started appearing on television screens across the nation for the first time. With an explosive demeanor that was both entertaining and objectionable, the Buckeyes' leader grew into a national icon himself, becoming the face of Ohio's flagship university.

While the statues, street signs, and massive practice facility on Olentangy River Road pay tribute to his many accomplishments on and off the football field, what he meant to the evolution of the game he coached is often overlooked. Over a half century after he took the job in Columbus, with another coaching icon now entrenched in the same position he once held, the parallels between Hayes and Urban Meyer cannot be ignored, as both helped advance the strategies and tactics used by coaches at every level to change the way the game is played.

Much the same way Meyer is credited with developing the 'Spread' offenses that proliferate today's game, Hayes held a similar association with the old 'T-formation' that dominated both professional and college football in the 1940s and 50s.

Though originally invented by Walter Camp in the late 19th century as one of the original formations in American football, the 'T' had fallen out of favor in the first few decades of the 20th century, as Pop Warner's Single-Wing shotgun set became the norm. But once coaches realized they didn't have a Jim Thorpe of their own to feature as both a runner and passer, the T-formation's systematic approach came back into popularity after George Halas' Chicago Bears pummeled the Washington Redskins 73-0 in the 1940 NFL championship game as Sid Luckman took the snap from under center with three backs behind him.

Other coaches, such as Stanford's Clark Shaughnessy, Notre Dame's Frank Leahy, and Texas' Dana Bible helped resurrect Camp's system and adapt it to the rules and tactics of the time. By the time Hayes took his first head-coaching job at Denison University in 1946, he had become a believer in the philosophy that was more dependent on the efforts of all eleven players instead highlighting only one.

As the name would suggest, the T-formation featured a quarterback taking the snap directly from the center with three backs lined up parallel to the line of scrimmage behind him. There were no wide receivers as we'd know them today, with the biggest pass receiving threats coming from the 'Ends' on either side of the formation, who today would just be called tight ends.

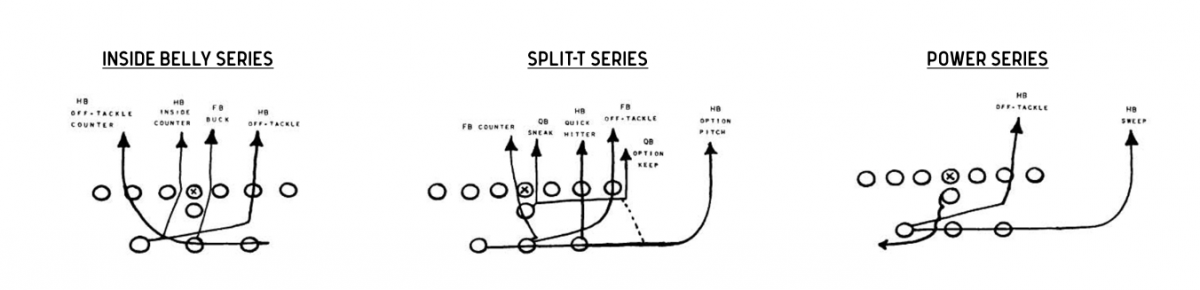

Although the formation didn't appear to offer much in terms of versatility, Hayes had three distinct approaches to attacking the defense, although the 'Inside Belly' series became the most prominent. Hayes looked to attack the defense between the tackles, setting them up with misdirection in the backfield and relying on his quarterback to carry out a series of fakes while handing the ball to the assigned ball-carrier in stride.

With such little space to carry out a dozen or so different concepts, Woody's linemen were drilled to recognize defensive fronts and adjust as needed. The tackles on either side were tasked with calling out these adjustments, looking to create better angles on their targets or gain an advantage by throwing a fourth blocker at three defenders, a philosophy that remains at the core of offensive football strategy today.

These real-time tweaks became the foundation of Hayes' offense, which he'd detail in his 1957 playbook:

Two years ago when coach Doyt Perry got ready to leave us to take the head coaching position at Bowling Green State University, I asked him what were the biggest weaknesses he felt we had. He diplomatically mentioned a couple of them and then hastily added, "I'll tell you what your greatest strong point is - your blocking adjustments. Don't ever give up on them."

He went on to explain that when he had come with us four years before, he felt these adjustments were too intricate to learn. But in establishing an offense in a league with the calibre of defenses we meet each Saturday, he felt it was the one thing above all others than had helped us to move the ball with consistency.

Such adjustments are common today, even at the high school level. But at the time, such modifications were rare, theoretically giving Woody's offenses the ability to run the same handful of concepts against any defense.

But although these interior plays made up the majority of Hayes' play-calls, giving credence to the 'Three yards and a cloud of dust' moniker given his style, he also included a handful of more progressive running elements with the 'Split-T' series. These concepts were the product of Hayes' time spent with legendary Oklahoma coaches Bud Wilkinson and Gomer Jones in 1952, who had made the 'T' all their own by widening the linemen's splits and running around the ends by incorporating ideas that were the pre-curser to what we now call 'option' football.

The idea had been initially brought to the forefront by Missouri coach Don Faurot, who patterned the idea after a 2-on-1 fast break in basketball. Ironically, Faurot had been the lead candidate for the Ohio State job when Hayes was selected in 1951 and turned it down, yet his signature offense still made its way to Columbus.

But Hayes' strength was incorporating these many styles into one game plan. He'd pound the ball inside with the Belly series, then send the quarterback darting around the end on an option or bootleg, and then catch the defense flat-footed by running a counter of a Wing-T alignment as one tailback lined up behind the end and took a handoff going the opposite direction.

Woody was famous for holding a conservative stance on the passing game, and the numbers back up that claim. According to John Lombardo in his 2005 book, A Fire to Win: The Life and Times of Woody Hayes, the Buckeyes' run-pass ratio skewed heavily to the ground game, as evidenced by the 1956 team that tallied 2,468 rushing yards compared to just 278 yards through the air.

Hayes wasn't afraid to admit his shortcomings as an aerial architect, as evidenced by an interview former star tackle Jim Parker gave to the Columbus Dispatch when asked whether his former coach would ever consider coaching at the professional level.

“He talked to me about it,” Parker said. “He said the only way he’d go was if I’d go with him. Then he said, ‘But, hell, I don’t know enough about the passing game.’ Passing game? Hell, we were lucky to pass 40 times a season.”

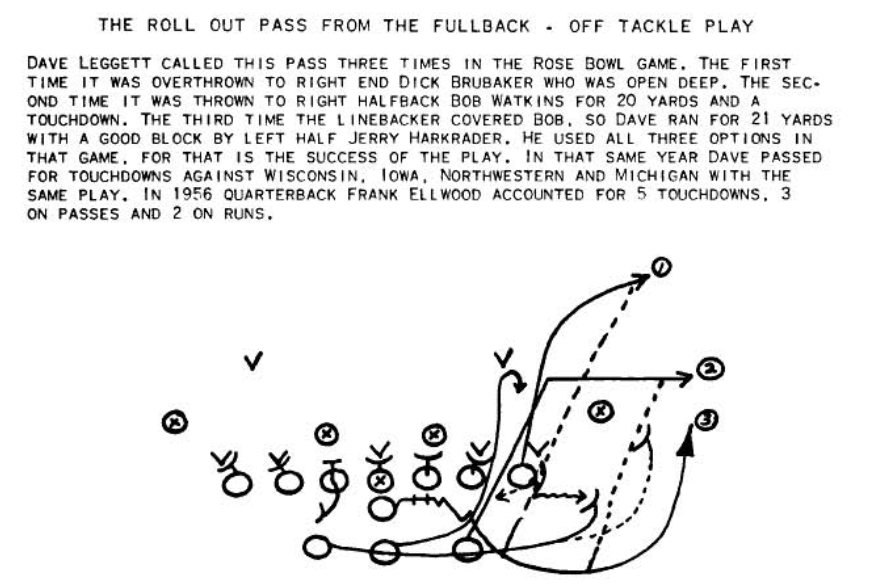

When they did throw the ball, Hayes' teams did so as a constraint to the base running game, using what is now known as 'play-action' to suck in defenses before running simple pass patterns targeting the halfbacks and ends.

Though Woody was as paranoid and competitive as any coach of his era, that didn't mean he kept these secrets to himself. At the time when technology didn't allow for the sharing of information even remotely close to what we're used to today, clinics were one of the only ways a coach could learn anything new about the game.

Having been a benefactor of such knowledge sharing himself during his the first decade of his career, learning how to install the 'T-formation' before his first season at Denison, Hayes became a regular speaker on the clinic circuit himself. His consistent attendance at these clinics wasn't purely out of altruism, however. Gracing the lectern at such seminars provided Hayes a level of stardom within the profession itself that counter-balanced his rotten behavior on the sidelines, while also giving him a chance to scout up-and-coming talent within the coaching ranks.

But Woody didn't stop there. He published his own playbook not once, but twice, in 1957 and 1969, allowing anyone to learn and understand the basics of his trademark schemes. Though the books were pre-cursors to the soft-skill management tutorials that would become commonplace for his successors, Hayes' volumes were clearly meant for the men of his own profession, given the way he'd deliver an entire paragraph describing the responsibilities of the right guard on his 'Fullback Buck' play within the pages.

As we know now, the old coach was obsessive about winning, in ways that didn't always help. Despite winning three national championships in his first 11 seasons in Columbus, the game had begun to change by his third decade one the sidelines. From 1962 to 1967, the Buckeyes failed to win a Big Ten title, creating quite a few empty seats in the cavernous Ohio Stadium on many Saturday afternoons. Not only was the team itself slipping into mediocrity in the win-loss column, Woody's teams simply weren't that exciting to watch.

Before the 1967 season, though, Woody did something revolutionary (for him, at least). Not only did he begin recruiting aggressively outside of Ohio, bringing in All-American talents like Jack Tatum, John Brockington, Jan White, and Tim Anderson, Hayes brought in some new faces on the coaching staff. While Lou Holtz famously joined the program for one season in 1968 to coach the defensive backfield, the 1967 hiring of a Pennsylvania high school coach, George Chaump, to coach quarterbacks may have been the most important decision Hayes made in the back half of his career.

Hayes and Chaump would go on to win two national titles in 1968 and 1970 while missing out on a handful more during Woody's final decade in charge of the Buckeyes. But those teams featuring stars like Rex Kern and Archie Griffin looked far different than the ones for which Woody had become known.

Next week in Part 2, we'll examine how and why Woody Hayes finally gave up on the old 'T-Formation' to produce the most famous and productive teams of his career.