Try to name a film set in Mississippi that isn’t tinged with racism.

It’s actually easier than it may seem, even as you fumble through The Help, Mississippi Burning, Ghosts of Mississippi, (anything with Mississippi in the title, really) A Time to Kill, Life, In the Heat of the Night and O Brother, Where Art Thou?

Perceptions of Mississippi outside of the region are still largely shaped by the television images from the Civil Rights movement. You see the image of a burning cross and Mississippi isn’t just one of the top five answers on the board; it is the top answer. It’s all you need to know if you’re into the convenient packaging of moving pictures depicting places you’ll never go, populated by people you’ll never meet.

James Meredith, escorted to class in 1962.

James Meredith, escorted to class in 1962.

The perception of Ole Miss football outside the region is even less complete. The Rebels haven’t won the SEC in nearly 50 years, so they’re rarely discussed on the outside. Even Minnesota and Indiana have each won the Big Ten in that span (and the Gophers have also beaten the Crimson Tide more recently).

Adding to the Rebels’ mystery: The program barely ever ventures out of its footprint on purpose. Ole Miss is winless against the Big Ten in just four meetings, has never played a Pac-12 team, is 0-1 against the Big East and 1-2 against the Mountain West.

The sites for Ole Miss’ purposeful football exhibitions are connected by short bus rides from Oxford or commuter flights not long enough for beverage service.

Ole Miss football is the hermit kingdom of the SEC, held under the oppressive thumb of Kim Jong-Reb for decades. There are some dispatches from Oxford that make it to the outside world: The boys wear ties to football games. The girls all major in animal husbandry and are anatomically flawless. Archie Manning and his youngest son played there. And everyone saw The Blind Side.

Ole Miss football is the hermit kingdom of the SEC

Beyond those novelties, all that we outsiders (see: Yanks) have to judge Ole Miss football is its exported imagery: That recently-discharged Colonel Reb, those stubbornly-flown Confederate flags, the uniforms bearing a curiously strong resemblance to those worn by Union foes between 1861-1865, that Dixie song, and finally, losing too many battles.

Yes, some metaphors are just better than others. This is where Ole Miss football is without peer.

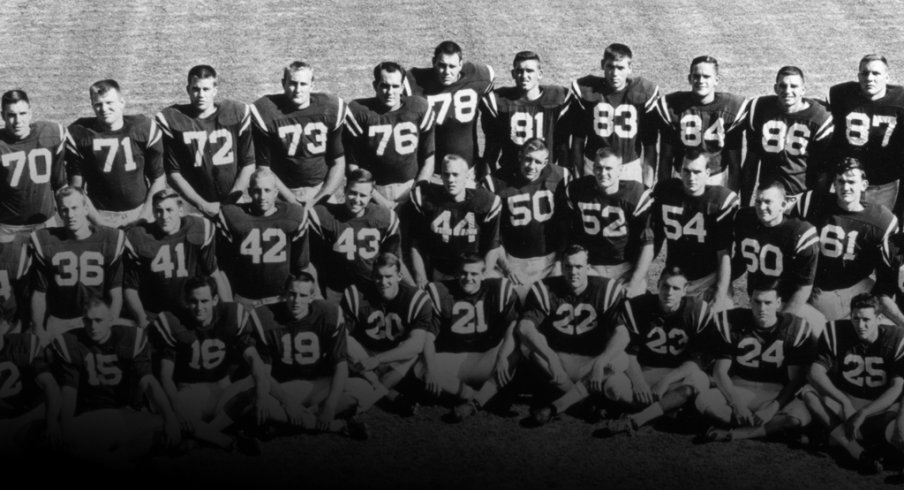

Clarksdale native and ESPN senior writer Wright Thompson began to examine the South after he had grown up and moved away. That’s when he first discovered the story of the 1962 Ole Miss football team from a half-century ago. Remember how the Rebels haven’t won the SEC in nearly 50 years? The ’62 team was the finest one of its most recent dynasty and possibly the best in school history.

That team served as the backdrop for Thompson’s Ghosts of Mississippi which has been adapted into the latest installment of ESPN’s documentary series, Ghosts of Ole Miss. It’s the largely forgotten story of the ’62 team’s gridiron journey which was obscured by the riots surrounding James Meredith becoming the first African-American to attend the university.

The film provides convenient packaging for the time period, but it’s far more than that: Ghosts of Ole Miss is a disquieting glimpse into a heritage that the University of Mississippi has repeatedly tried to expunge, reshape and embrace simultaneously.

And yes, of course it’s tinged with racism. It’s got Miss right there in the title.

[If you are still trying to name a Mississippi movie that doesn’t have racism sewn into it story, look no further than Biloxi Blues. Or Crimes of the Heart, My Dog Skip, The Long, Hot Summer, Cookie’s Fortune or Crossroads - the one with Ralph Macchio about blues musician Robert Johnson, not the Britney Spears one. That one took place in Louisiana.]

Back in early 1998 my parents informed me that they would be leaving my hometown of Columbus, OH to pursue opportunities elsewhere. I was 24 at the time and living on my own in Chicago, so this development affected my holidays and little else.

They had not yet determined exactly where my future Thanksgivings and Christmases visiting them would be spent, but they shared with me their Final Three. “Home” was going to be near one of three campuses where they would work: Princeton, Stanford or Ole Miss. Jersey or the Bay Area, I thought at the time. It’s not Columbus during Ohio State-Michigan week, but it definitely could be worse.

My parents had previously lived in New York and San Diego before settling at Ohio State for my formative years. I never considered the South a legitimate contender for their next move. Mississippi is not a destination. People just happen to be from there. Its presence among the Final Three was little more than column fodder, an unnecessary baseline comparator for Palo Alto and Princeton.

A month later in Chicago I got the call: Column fodder was triumphant. My Lebanese immigrant parents had chosen the Deep South over the coasts on account of a research grant being funded by money from the Big Tobacco settlement that would soon be depicted in the 1999 Russell Crowe/Al Pacino film The Insider (which was shot in Pascagoula - there’s another non-racial one for your burgeoning list).

Everything I knew about Mississippi I learned from my television, Tennessee Williams or William Faulkner.

It was an upset that rivaled Charles Woodson stealing the Heisman from Peyton Manning: A possibility all along, but assumed to be more of a novelty than an inevitability. My family was actually moving to Mississippi.

Everything that I knew about my parents’ future home state I learned from my television, Tennessee Williams or William Faulkner, which made it both bleak and beautiful. But goddamn it I was really looking forward to getting into San Francisco or Manhattan in winters, not to some place in the sticks where the Confederate flag was defended, revered and still displayed publicly without shame.

Speaking of sticks and incendiary flags, Dr. Robert Conrad Khayat was the Ole Miss chancellor back then. He found the Stars and Bars appalling and was forced to deal with the challenge of extricating the symbol of Southern defiance from the Rebel faithful without violating their freedom of expression. Dr. Khayat was trying to get a Phi Beta Kappa chapter established on campus and believed that the perception of being a “racist school” would undermine that initiative.

U.S. Marshals bracing for a riot.

U.S. Marshals bracing for a riot.

Southern defiance is exactly what he got in return for trying to take away their precious flag, as the backlash turned into a defense of all Ole Miss traditions. Try and find one that doesn’t carry racial overtones: The school’s nickname, its mascot, that flag or campus streets like Confederate Drive, which has since been renamed Chapel Lane. They were tumors wrapped around the University of Mississippi’s reputation. Phi Beta Kappa probably wouldn’t touch Ole Miss with a ten-foot...pole (more on that in a bit).

Over a decade earlier, removing the Stars and Bars from the state flag in favor of a more unifying emblem had been brought to vote by then-governor William F. Winter. The votes, which were cast entirely along racial lines, came out in favor of keeping it the way it was. It indicated that as long as there were more whites than blacks in the state, the status quo would probably have the necessary numbers to maintain preservation. The Ole Miss chancellor was forced to get creative.

“Khayat said that if these guys are going to keep bringing in those flags, we’ll just get rid of the sticks,” Ghosts director and Peabody Award winner Fritz Mitchell told me. “So the athletic department banned flag sticks because they posed a safety hazard. Sticks were eliminated: Corn dog sticks, flag sticks, all sticks. Just blame it on the sticks.”

The ban on bringing sticks into Ole Miss games remains today.

The ban on sticks at Ole Miss games remains today. Those little pervasive pom-poms that can be seen in any SEC stadium carry specifications at Vaught-Hemingway Stadium: They are required to have rounded plastic handles. That’s just to keep all of the incendiary sticks out of the game.

Khayat retired from Ole Miss in the summer of 2009. That same year Ole Miss banned the playing of From Dixie with Love by the band at games, because "the South will rise again" was routinely chanted by fans toward the end of the medley. The university had tried unsuccessfully to stop that tradition, but the fans would not relent, shouting the phrase even more enthusiastically once they were told to stop. That old, reliable Southern defiance had struck once again.

So Ole Miss just banned From Dixie with Love from being played entirely. No more song. And no more sticks.

Ghosts of Ole Miss doesn’t waste any time getting to the point. The film opens with the reenactment of a giant cross burning in the front yard of Thompson’s childhood home.

His parents were absorbing the consequences of being politically active against the status quo in the Mississippi Delta. Thompson, whose brilliant autopsy of the chaotic 1962 season is the vehicle for the documentary, details his search into that Rebel team while trying to better understand why he knew nothing about it despite being one of the greatest teams to ever play college football.

In trying to unearth the rationale for keeping this precious and rare chapter of football excellence a secret, Thompson asks himself two conjoined questions: What is the cost of knowing our past?

And what is the cost of not?

The most remarkable football season in Ole Miss history took place as the university was openly self-destructing over the admission of a single African-American student. Segregationists led by Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett battled federal and state forces over Meredith’s admission to the school. Two people – a French journalist and an electrician, both bystanders – were executed in the mayhem. The rest of America observed in amazement while the Kennedy White House watched closely with concern.

Oxford started to get sideways in late September. Two months earlier, Faulkner had died of a heart attack.

Among the least earth-shattering revelations in American history is that the North welcomed racial integration more swiftly than the South did, but that’s just too vague of a point. What’s more fascinating is that nearly a full century after the Civil War had concluded American soldiers were invading the state of Mississippi again. And as was the case 100 years earlier, it was on account of racial strife.

THE 1962 OLE MISS TEAM WAS VIEWED AS BEING “THE LAST CONFEDERATE SOLDIERS.”

The first black football player for the college in the town where I grew up was a defensive lineman named Bill Willis. His number 99 is permanently affixed to the overhang in C-Deck in the closed end of the Horseshoe and won’t ever be worn again. Willis had played on Ohio State’s national championship team 20 years prior to the Ole Miss riots, in 1942.

While Meredith was under armed protection just trying to become the first African-American student to enroll at Ole Miss, Willis was already doing charity work in Columbus a full decade into his retirement from a Hall of Fame NFL career. They were black men living in the same country, but under radically different circumstances.

Meredith and Willis’ respective campuses are just a little more than 600 miles apart, but despite being 20 years the elder and enrolling at Ohio State over a decade before Brown vs. Board of Education, Willis’ celebrated steps on campus had been greeted by raucous cheers across the racial divide. Meredith’s steps required the President of the United States to dispatch the Army’s 503rd Military Police Battalion to join the US Border Patrol and the Mississippi National Guard in keeping the peace among the state’s own citizens.

Those 600 miles are a lot further apart than they may seem. Context makes it brutally clear why it’s so difficult to celebrate that magical 1962 season in Oxford. Too many guns. Too many helicopters. Too much embarrassment. Too much tragedy.

“That Ole Miss team gets lost in time,” said Mitchell, who also directed the 30 for 30 film on Jimmy the Greek. “It’s forgotten. People want to be more interested in current events. A lot of events from the Civil Rights movement get folded into Hollywood movies, but for young people – and some older ones too – this will be a fresh story. I’m not sure very many people (beside Thompson) have been able to make connections between the riots and the football team.”

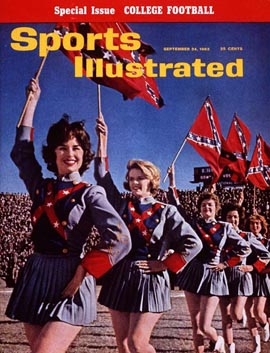

The connection was deeper than people think. In his interviews for the film, Mitchell was told repeatedly that the 1962 team was viewed as being “the last Confederate soldiers.” Before each game the Ole Miss cheerleaders would run out onto the field with that giant, unmistakable battle flag of the South. This game day tradition only began after Harry Truman, whose ancestors were slave owners, became the first president since Abraham Lincoln to address the Civil Rights issue.

Sports Illustrated, Sept. 24, 1962

Sports Illustrated, Sept. 24, 1962

His White House injected itself into the issue of segregation, and as a result the flags came out on Saturdays in support of the team in the blue/gray uniforms. It was a Civil War reenactment with blocking and tackling instead of cannons and bayonets. Fast-forward to 1962 and the university was in the throes of an actual battle for segregation while its football team was pursuing an undefeated season. In hindsight Ole Miss might have been shut down were it not for its perfect Rebels.

Preserving the traditions of its dead ancestors had been a vicious battle in Mississippi since the Reconstruction. As with all wars, at some point the cost and benefit need to be reevaluated.

“(Governor Winter) basically told me it has gone on for far too long,” said Mitchell. “Enough is enough. Mississippi should focus more of its time and efforts on education and health. It’s such a poor state economically, ranking near the bottom in so many categories and investing so much energy in this just wastes a lot of time. How far do you go?”

Some of those involved in the riots stopped fighting long ago. You can’t go back and change who you used to be; you can only change who you are and who you become. Bobby Boyd, a third-string QB in 1962 – as well as a member of the Ole Miss baseball team – had been personally involved in the rioting and is among those who have since let go.

“Boyd came in (to be interviewed) and almost did a mea culpa. He was horrified at how the state, the team, he himself and everyone had treated Meredith. He said that no one should be treated like that. But to a man, who is going to admit to being a racist? We heard a lot of, 'we were just trying to play football. We were just trying to win games.' That’s just the way the South was. It’s a hard thing to say about yourself.”

Meredith was ultimately admitted to the University of Mississippi and eventually graduated with a political science degree long after the riots had been quelled. But the story of the riots didn’t necessarily end with the troops drawing down, Meredith collecting his syllabi or even the Rebels concluding their march through the SEC en route to the Sugar Bowl.

Just two weeks following the riots the biggest crisis of the Cold War began. The Cuban missile crisis pushed the country toward nuclear conflict, and Oxford abruptly fell off of America’s front pages as the riots slipped out of the nation’s consciousness. Its aftermath was lost in the global fear over medium and intermediate-range ballistic nuclear missiles being pointed at America from 100 miles off her coast.

After making their choice, my parents began house hunting in a nice suburb not far from the University of Mississippi Medical Center. As they explored the space of one particular house, the realtor who had accompanied them did her best to bring value to her new clients.

“I need to disclose something to you,” she said solemnly. “There is an African-American family that lives on this street, just a couple of houses down from here.” She communicated this news earnestly, making sure that these homebuyers from Ohio understood everything about the purchase they were considering.

“Why are you telling me this?” My mother asked in disbelief. “If we buy this house do you have to disclose to other buyers in the neighborhood that we’re Arabs?”

“Oh, of course not,” she replied calmly. “That’s different. This is just something I need to tell you.”

It was reflective of the market the realtor was accustomed to. She was there to do exactly two things: Sell a house and gain a source of future client referrals. Providing a disclosure like that was more a function of fulfilling the latter goal than tipping her personal views on race. That’s what markets do. They respond to the demands of the people and they’re largely utilitarian. The majority rule, which is why Winter’s unifying symbol initiative fell to the will of racial divide.

And she was selling a house, the same way that Khayat was selling the University of Mississippi to Phi Beta Kappa. You can change the market only by shaping the demands of the people, which defiantly prefer to shape themselves. Southern defiance is just one of many flavors of market demand. It cannot be recalled; it can just be shaped into Southern acceptance. And like so many aspects of the South, that shaping happens very slowly.

Dan Rather reporting from the riots.

Dan Rather reporting from the riots.

Ghosts of Ole Miss concludes with a glimpse into that metamorphoses, which contrasting against the events of 1962 demonstrate just how much the culture has changed despite the imagery that has been exported from the SEC’s hermit kingdom for decades. It probably isn’t enough to change the minds of outsiders, but that’s just because it’s difficult not to judge a book by its author.

The South berthed Ole Miss, and Ole Miss is the South. The perception is anchored to the past and still lags behind. Regardless of the real changes in actions and attitudes – Ole Miss’ reigning Homecoming queen is Courtney Pearson, an African-American student who overwhelmingly won the popular vote – the university is still pinned beneath that perception which took decades to construct upon itself.

But Ole Miss will rise again from that perception – it is an inevitability. The catalyst for the 1962 riots was developed over centuries. That culture was baked in, and it is now slowly being bled out.

Some Ole Miss students and stakeholders were nervous about how this film will paint their school and, by extension, themselves. I think they’ll be understandably disturbed by some of the footage, but they’ll be pleased with how the story is captured and told. You can’t change where you’re from. You can’t go back and change who you used to be; you can only change who you are and who you become.

Thompson and Mitchell put a humble and promising bow on the film, which differs only slightly from the story on which it is based. In a series defined by so many well-constructed and substantive chapters, it’s very difficult to name a single 30 for 30 film that is significantly better than Ghosts of Ole Miss. It’s even harder to name one that is more important.