2020 was not a banner year for football innovation.

While coaches across the country had more time than ever to immerse themselves in zoom clinics and a never-ending supply of All-22 film available online, the inverse was true when it came time to implement those learnings. As players at all levels of the game spent their time at home, rather than on the field or in a meeting room, the challenge of basic organization took priority over the installation of a new scheme.

As we saw from Ohio State in 2020, this could be a double-edged sword. On defense, Kerry Coombs had little choice but to run it back with the same system installed the year prior (while he was with the Tennessee Titans), as it was what his players knew they could run. Unfortunately, many opponents knew the system just as well, leading to some embarrassing performances in the secondary.

On the other side of the ball, though, the Buckeyes may have benefited somewhat, at least in comparison to those same competitors. With eight returning starters, including the best quarterback in school history, Ryan Day didn't need to go back to the drawing board, as continuity proved to be a winning strategy.

Even without J.K. Dobbins, the OSU running game relied on the same, Mid Zone scheme that had been so effective the year prior, with Trey Sermon eventually picking up where the newest Baltimore Raven had left off. With the threat of a punishing ground game still there, Day could dial-up deep, play-action passes to take the top off with Chris Olave and Garrett Wilson streaking down the sidelines, and the result was the seventh-most dangerous offense in all of college football last fall.

Though those elements may have been the defining characteristics of the Justin Fields offense in Columbus, it's not as if Day's system was truly that simple, of course. This is still the modern Spread era, so the Buckeyes have been known to incorporate the occasional option element from time to time.

As we can see in this clip from the Big Ten Championship Game in 2019, Fields had three options on one play:

- Throw a quick hitch to the X receiver (Bin Victor) on the right

- Throw a Look screen to the left

- Handoff to Dobbins on a Mid Zone run

Unlike a zone-read play, in which Fields would make his decision based on the movement of a single defender after the ball is snapped, the quarterback's decision tree takes place entirely before the play begins. Seeing the cornerback across from Victor playing with a 10-yard cushion, Fields knew he could quickly fire a pass out to the edge and get his receiver one-on-one with a defender in space, and one missed tackle would mean six points for the Scarlet & Gray.

Even though the corner does a good job of corralling the receiver long enough for help to arrive from his teammates between the hashes, the offense has still picked up an easy five yards.

Had the corner been pressing up closer to Victor, Fields' next read is the Look screen (because the receiver simply turns and looks for the ball without moving) to the opposite side. While there were three defenders over the receiver and his two blockers, two of those defenders are playing with a deep cushion, meaning the third, unblocked defender would have had to make up over 10 yards just to get a hand on the ball-carrier, making this an equally attractive option.

Only if the defense was playing tight coverage on all four receivers would the handoff be in-play. Such play-calls make the 'run' element of the Run/Pass Option a relative safety hatch, used only when absolutely necessary.

In 2020, the Buckeyes began employing more traditional RPOs, attaching a backside hitch or slant to a running play to quickly spread the ball to Olave or Wilson if the defense focused too much on stopping the run. But they also took the option game one step further by taking many of the concepts and teaching points of an RPO and applying them strictly to the quick passing game.

Going back to the days of Bill Walsh, offenses have split the field in half and run different passing concepts to each side, using the defense's pre-snap alignment to determine which side to attack. Over time, defenses countered by masking their intentions and giving false signals in hope of baiting the QB into making a dangerous throw.

When an offense empties the backfield and spreads all five eligible receivers from sideline-to-sideline, however, the defense has little option but to show its cards. The offense may no longer have the safety valve of an inside handoff on which to rely, but it has a clear picture of its opponent's intentions.

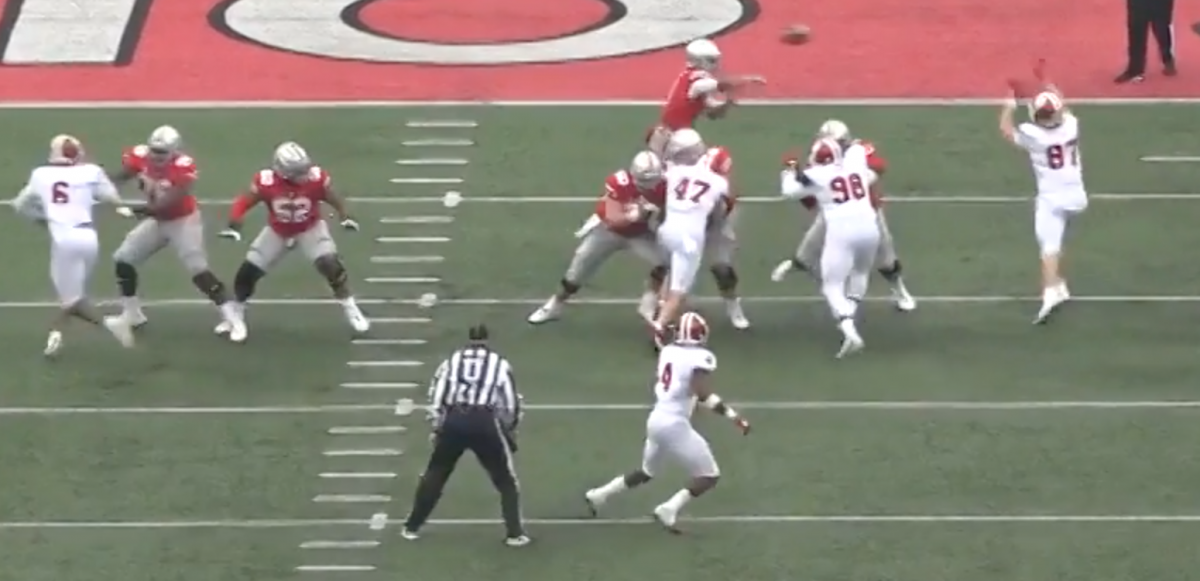

For example, this looks like a simple, quick screen to Olave:

In reality, though, Fields had two very different concepts working on either side of the field.

Showing a two-deep safety look, the Indiana defense can only press up two defenders at the line across from a three-man bunch, giving the QB the signal to quickly get the ball out like a shortstop throwing to first base.

In concert, the offensive line isn't worried about creating a traditional pocket. Rather, they all slide in one direction to take away any inside pressure, forcing unblocked defenders to take the longest route possible to the ball. While the defensive end, #87, gets a good jump on the snap, he's still unable to disrupt the throw.

All of a sudden, the ball is outside the hashes and in the hands of one of the most explosive human beings in the stadium. The unblocked safety gets caught up in the wash of the blocks in front of him, and a streaking linebacker from the middle of the field is in no position to make a tackle, allowing Olave to pick up huge yardage.

But what happens if the defense presses up to take away the screen before the snap? Such was the case when the Buckeyes called a similar play in week two at Penn State.

On this occasion, the screen was actually a bubble screen to the inside-most receiver, tight end Jeremy Ruckert. But the defense showed press-man coverage, signaling to Fields that he should look the other way.

As Fields looked to his right, he saw Wilson out wide with his running back, Sermon, in the slot. He also noticed the edge defenders showing blitz instead of manning up on the back.

But rather than making his decision before the snap, this time Fields would have to wait. Wilson and Sermon would run a Slant/Flat route combination, and the QB had to wait and see the movement of #13, the potential flat defender.

If he followed Sermon in man-coverage, the slant to Wilson would be open. If he dropped into a zone, the back would likely be sitting all alone outside the numbers as the cornerback bailed out deep.

As we can see, #13 scrambled to cover Sermon in the flat, signaling that the defense was in man-coverage. Fields simply completed his drop and delivered an easy throw for a first down.

To assemble this play-call, Day didn't need to teach his players anything new. Fields already knew how to make the pre-snap read for the screen to one side, while the post-snap slant/flat throw is taught to sixth-grade quarterbacks. The crucial details come simply in knowing how to set up the concept.

Any screen concept could be substituted, as could the two-man routes - replacing slant/flat with double slants, curl/flat, fade/out, smash, or many others. More important than the routes themselves, however, are the players executing them.

As you may have noticed, although the Buckeyes lined up in an empty set, they did so in 12 personnel (1 back, 2 tight ends), rather than with five true receivers. This was important for two reasons:

- It forces the defense to declare its intentions by dragging linebackers out to cover split out tight ends and backs in man-coverage, or keep its desired shape in a zone look - either way, the offense will know before the snap

- The offense can always audible to something else

This second point fits into the larger strategy of the Buckeye offense, as the unit regularly operates at a 'check with me' pace. What that means is Fields would get the team lined up, call a dummy signal to try and get the defense to show any late movement, then look over at Day with time still left on the play clock.

If the coach didn't like what he saw, he would signal in a different play that was better suited to what he saw from the defense. With two tight ends and a running back on the field, Day had plenty of options from which to choose, from an inside run play to a deep, play-action pass.

While the idea of running a Pass/Pass Option might sound exciting and innovative, it's all done in service of the larger offensive goals. Spreading a defense out and using the threat of a quick screen or slant is enough to get a defense to play more conservatively, which is exactly what Day wants.

Now, as the head man in Columbus has to break in a new starter at QB; one who will have never thrown a pass at the college level, concepts like this may become more prevalent. All three contenders for the job came from advanced high school systems that undoubtedly taught them to raw skills to make such decisions before and after the snap.

With Olave and Wilson back again, there's plenty of reason to expect the Buckeye coaches will take advantage of the option to get the ball in their hands early and often, keeping the defense honest and taking the burden off their young and unproven signal-caller.