Typically, high school football coaches spend the spring weekends in windowless hotel ballrooms or journey to their local college campus to learn from their peers at various clinics.

Similarly, college coaches will venture out to high schools all across the country for recruiting purposes, breaking down tape with high school coaching staffs in order to curry favor with any potential prospects.

But with nearly all such events canceled and an abundance of time on everyone's hands over the past few months, this process of knowledge-sharing has evolved in 2020, allowing for far more transparency than ever before. While not every coach at their level has been willing to divulge their secrets, Ohio State's Matt Barnes and Al Washington have been open about spreading the gospel of the system that earned their unit the top spot among FBS programs in total defense last fall.

Barnes was the first to open up about the Buckeyes' old school approach to stopping the pass when he joined the Call An Audible YouTube channel for a virtual clinic back in April, in which he touched on the various details of the Cover 1 man-coverage and Cover 3 zone employed by the Silver Bullet secondary. A month later, Washington made an appearance of his own, this time detailing how the OSU run defense improved from 57th to 9th nationally in just one year.

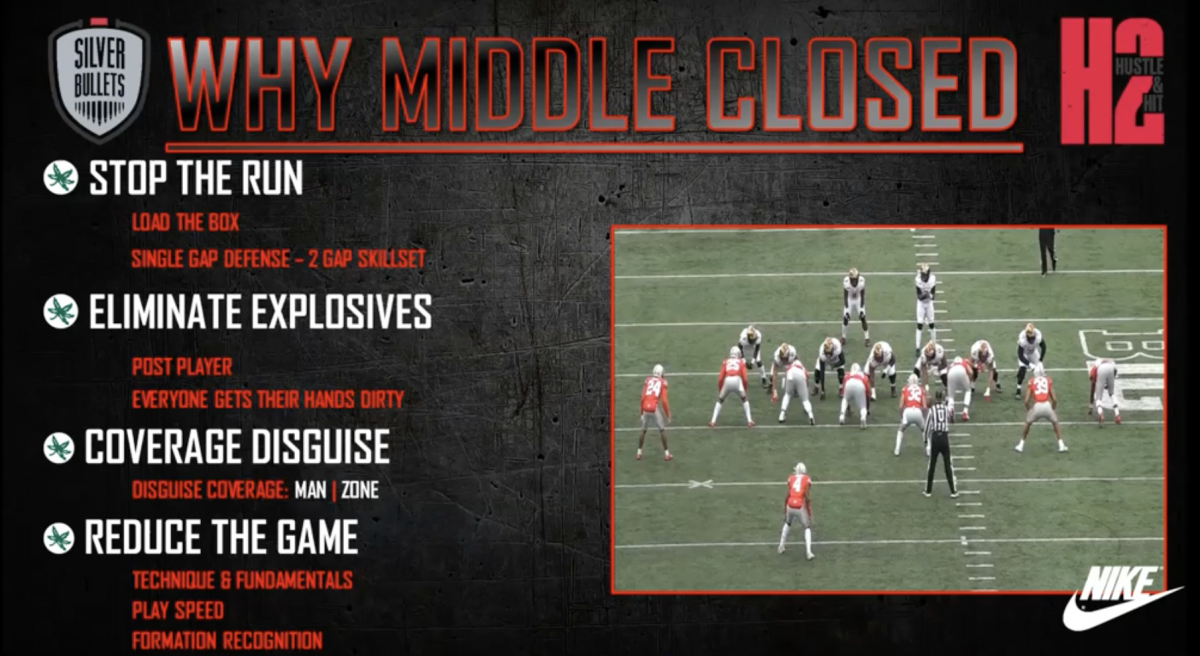

The OSU linebackers coach spent an hour detailing not only how he coaches his players on the fundamentals of the position, but why the team changed from a split-safety (two-deep) system to playing almost exclusively with only one deep safety. Coaches typically refer to the difference as Middle-Open (two-deep), as there is a space between the two, versus Middle-Closed, with the free safety sitting right between the hash marks on most plays, and adjust passing schemes accordingly.

With just one deep safety, the number of coverages a defense can employ is essentially limited to just variations of Cover 1 and Cover 3, which Ohio State used to keep opposing offenses off-balance. But the alignment of the safeties plays a major factor in the run game as well.

While offenses use body counts to determine whether they have an advantage in the run game, defenses count the number of gaps they must defend. As a second safety lines up closer to the line of scrimmage (a role effectively played by Shaun Wade last fall, despite his distinction as a cornerback on the depth chart), the Buckeyes were able to 'load the box' by placing one defender in every gap.

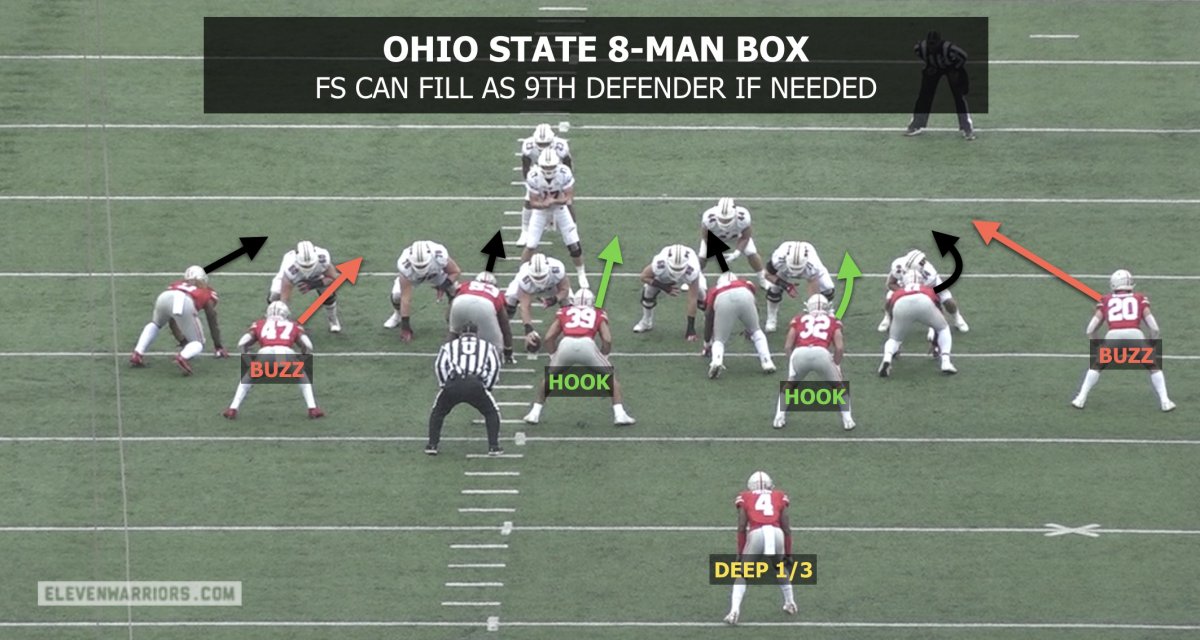

As Barnes laid out earlier in the spring, the OSU defense doesn't necessarily think in terms of conventional positions when lining up, rather, there are simply Hook, Buzz, Corner, and Middle 1/3 (free safety) roles which can be filled by a number of different players based on the play-call. But when the offense hands the ball off instead of dropping back to pass, the four Hook and Buzz defenders (of which Wade was often one) each were responsible for filling a run gap along with the four down linemen.

But the unit isn't simply designed to have each defender shoot in between two blockers and wait for the ball-carrier to arrive. Each defender also played a critical role in forcing the ball toward his teammates, corralling the runner, and minimizing any gains.

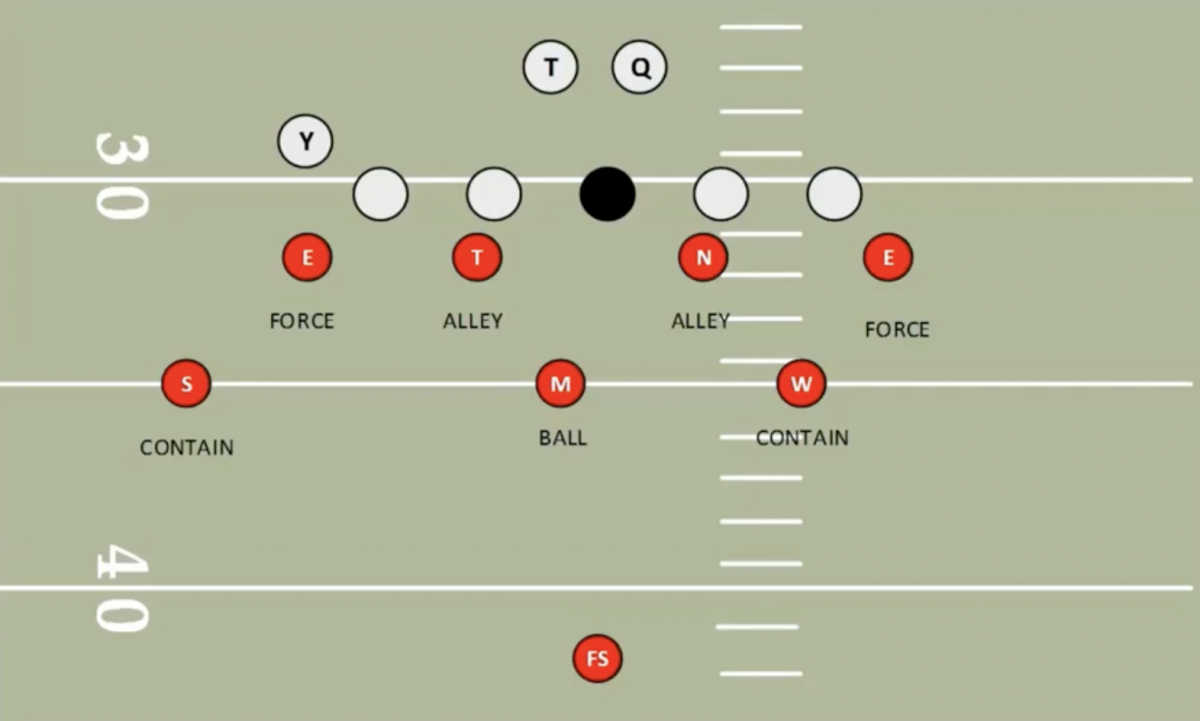

Based on the play-call, the interior players along the line (often the D-tackles) act as the Alley players, looking to penetrate and force the runner to bounce outside. Meanwhile, the ends became the Force players, keeping their outside arm free and always trying to turn that same runner back inside. The outside linebacker to that side is the Contain player, filling a similar role to the end and ensuring the back doesn't reach the edge and often make the tackle.

The middle linebacker (sometimes called a 'Spill' player) reads the action in front and fills his gap, but then chases down the ball-carrier to make the tackle after each of his teammates has leveraged the runner, making this a true team effort. If for some reason, the middle 'backer can't escape an opposing blocker, the free safety is in a similar role and can close on any runner that escapes, having had his eyes in the backfield throughout the entire play regardless of a run or pass.

It should have come as no surprise, then, that the top four tacklers on the OSU defense last fall were the three starting linebackers and the lone safety, Jordan Fuller.

This approach isn't just limited to the inside run game, as the same philosophy of creating the Alley-Force-Contain triangle is applied by the secondary against quick bubble screens outside. It's even employed by coverage players on the punt and kickoff teams, with the first player down the field acting as an Alley player who forces the returner to move laterally, knowing the Force and Contain players aren't far behind.

"We are leveraged in the run game," Barnes told a crowd of clinic attendees back in February. "What does that mean? It means we have edges. If you want to run outside zone to our left, we’re going to have a SAM linebacker shoot his gun and he’s going to put an edge on that thing right now. We’ve got an Alley player running inside-out to the ball."

Outside of the free safety, each of these roles can change based on the play-call, which could include on a blitz, twist, or stunt along the defensive line. But it's not as though the unit is split in half. Instead, they adapt their roles depending on the direction of the runner.

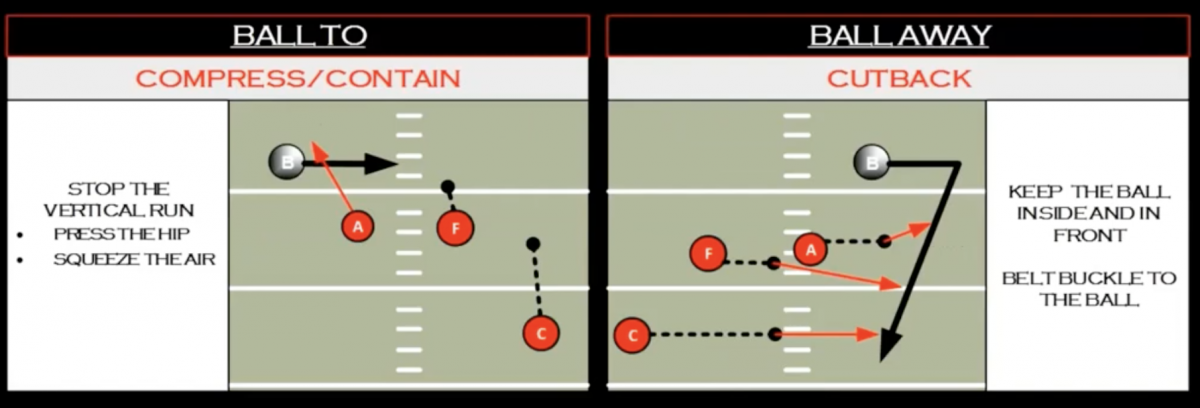

If the ball-carrier is heading to their side, the defenders are there to compress and contain him, as directed above. When the ball goes to the opposite side of the field, though, those defenders all become responsible for taking him down and ensuring there's no room to cut back upfield.

As Washington put it, the front side of the defense is trying to penetrate and force the runner to change direction while the backside defenders "build a wall" by filling every gap and closing quickly. If executed properly, there should always be one unblocked defender (or 'free hitter') left along the backside edge just waiting for the runner with open arms.

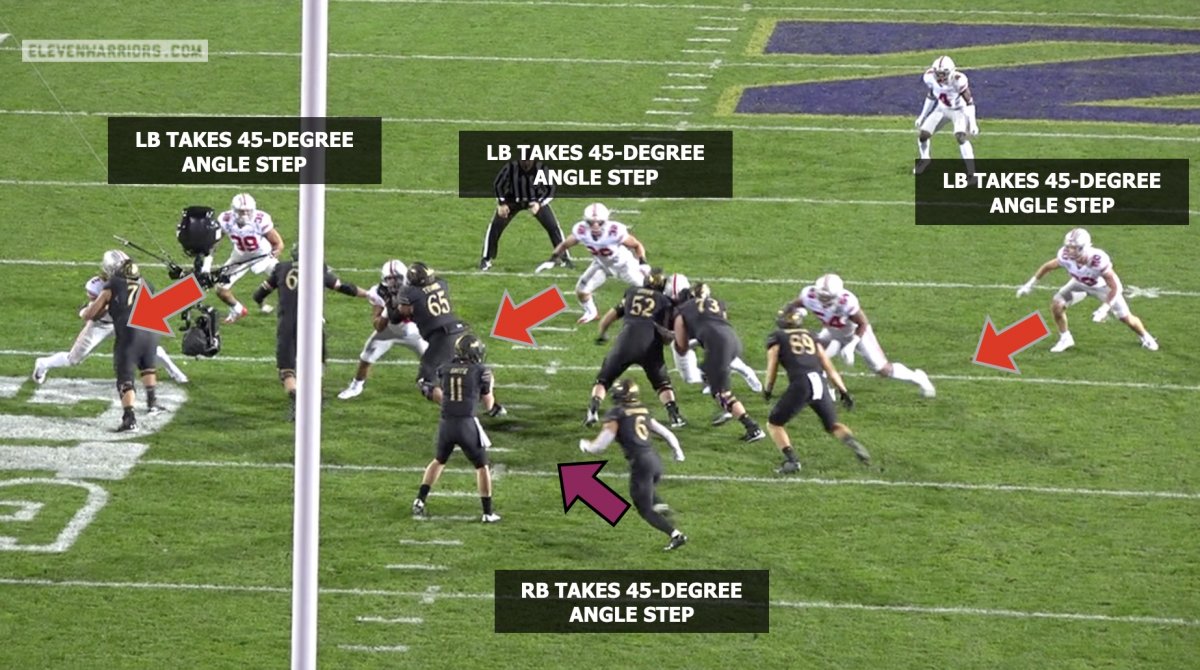

Not every run play is as simple as the inside zone clip shown above. The linebackers are responsible for adjusting their gaps and paths depending on what they read in the quick flashes following the snap.

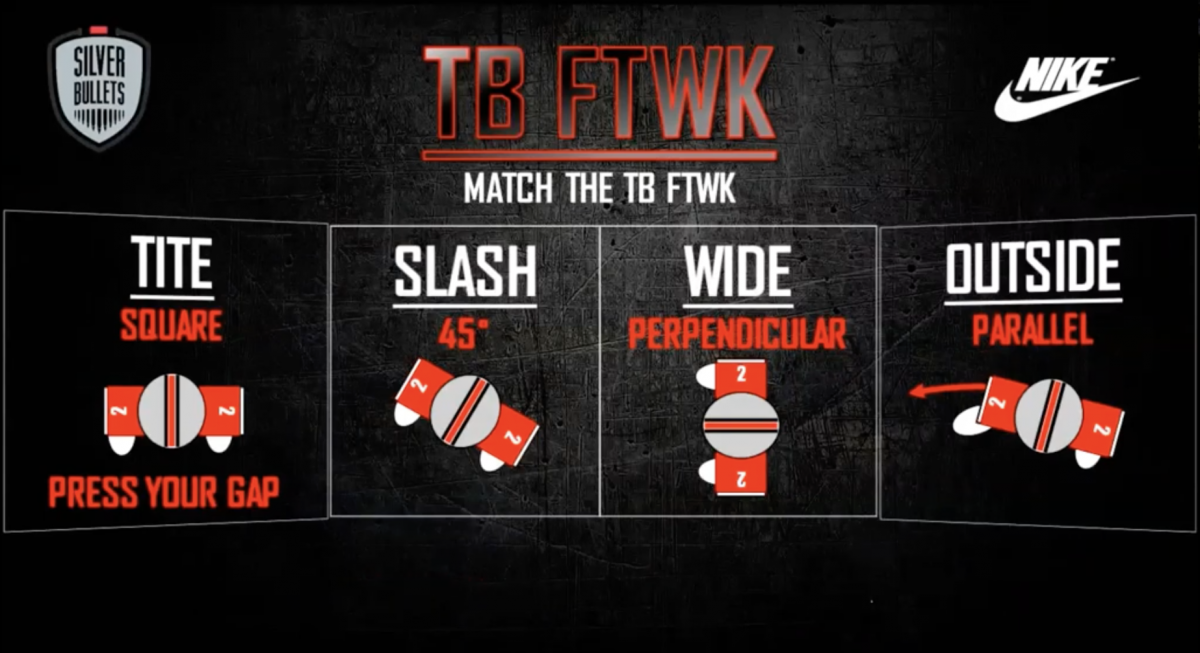

Many coaches teach their linebackers to read the offensive guards, as their paths will often dictate the true direction of a running play. But Washington believes those guards can sometimes be misleading, and he instead coaches his linebackers to mirror the initial footwork of the running back.

If the running back immediately squares his shoulders to the line, as in the clip above, then the play will come straight at them. But if he angles toward the sideline in any way, then the gap for which the defender is responsible will also widen out and he must respond in kind.

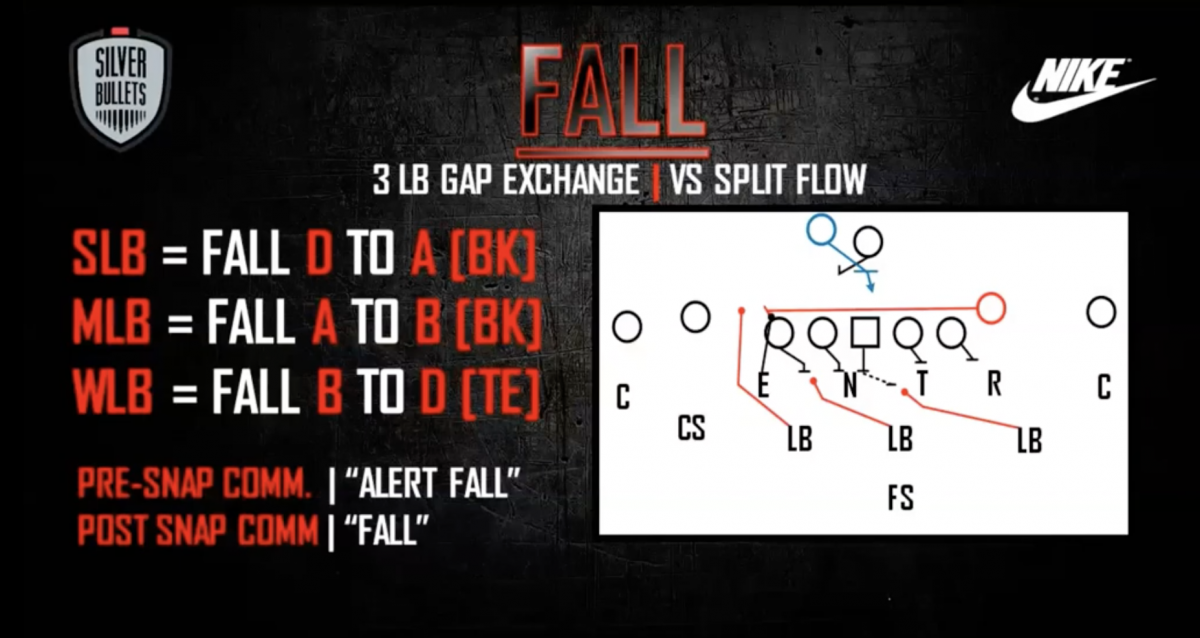

One way offenses will try to exploit this setup is by sending the tight end back across the formation to kick out the 'free hitter' and open up a cutback lane, often called split-zone (known as Crunch in the OSU offensive playbook). When this happens, the defensive line's gap responsibilities don't change, but the linebackers will all "fall" over to the next gap, ensuring no room appears for the runner.

The linebacker to the tight end side is responsible for alerting the other two linebackers to such action before the snap, but all three must be prepared to slide over immediately. When executed properly, gaps that appear open to the runner are quickly closed by flowing defenders ready to make a tackle.

The beauty of such a system is its simplicity, as the responsibilities do not change based on the pass coverage. In Greg Schiano's system a year before, the defensive front seven was easily manipulated as teams knew it was difficult for the unit to change on the fly, and many of the same players thrived under this new approach.

But just as was the case with the Buckeyes' prolific pass coverage, their success in stopping the run came from a mastery of fundamental techniques, not from the scheme itself. Washington and the other coaches focus a great deal on eliminating false steps, maintaining proper hand placement, and defeating much larger blockers.

By simply reducing the game into a series of one-on-one battles on the field rather than a chess match between play-callers in the press box. With a talent advantage in virtually every game they play, this approach will likely favor the Buckeye defense for many years to come.