Allegedly the suspicion first arose when coaches noticed a backup special teamer had suddenly become a film room junkie.

He wasn't just watching his unit's plays. This guy had taken an abrupt pivot from ordinary niche depth player to film room fiend devouring every bit of tape the team had - offense, defense, all of it.

The staff followed the scent and found reason to believe he was supplying an Ohio State fan site with insights which could be positioned commercially as exclusive insider information.

That's the speculation. His time with the program ended as abruptly as his film obsession.

Arguing this story's validity now is a hollow exercise, as the drama is well over a year old. But the environment to leak or share information intended to stay inside of any program's practice facility is, conservatively, ripe.

Benjamin Franklin famously said three people can keep a secret if two of them are dead. Ohio State has 118 living players on the current roster. About half are teenagers who have grown up in an era where every mundane detail of their lives is given oxygen - or worse, ends up being shared on an untold number of little screens.

Football programs are bastions of secrecy, from operations to game strategy. Players and coaches matriculate annually and take best practices with them to wherever is next, not unlike how employees and contractors have portable knowledge from work they've done at previous stops.

Javonte Jean-Baptiste just left Ohio State for Notre Dame. James Laurinaitis figuratively passed him on his way back home from South Bend. They'll stand across from each other in September, but on opposite sidelines from where they each stood last season.

That's on-the-level and generally accepted across industries, including football. A Coca-Cola executive could easily apply lessons from bottler franchising strategies they learned in Atlanta at a new employer somewhere else.

They just can't bring the Coca-Cola recipe with them. And leaking or stealing it could be a crime.

Compensation shapes behavior, especially in a sport where student-athletes only recently began receiving above-the-table remuneration. Compensation can come in many forms, but historically players were forced to accept school tuition rebates exclusively.

It's inflexible and carries no liquidity, which still creates an environment ripe for shadiness. Let's use the Buckeyes as an example: 89 of the current 118 football players are on scholarship, which means four of those guys won't be on the roster when the team visits Bloomington to kick off the 2023 season in seven months.

There's a decent chance at least two of them know they probably won't be around for the fall semester. Only a fraction of the other guys collect NIL benefits which could be considered substantial. Roughly 40 guys are practice players who will never see the field and the majority of them are on the hook for tuition and other college expenses.

The opportunity for duplicity has been ripe for decades, especially in amateur sports where bookmakers issue odds.

Every one of those players is granted entry ranging from exclusive to unfettered into the Ohio State football inner sanctum, which is to say they have keypad access to the Woody. Access to other players. To playbooks. To hallway conversations. To film rooms. From starting quarterback to backup long snapper.

The opportunity for duplicity has been ripe for decades, especially in amateur sports where bookmakers issue odds. But this environment has evolved quite a bit since the days of basketball teams shaving points in plain sight, like Tulane did in the mid-1980s or Boston College in the late 1970s at the behest of notorious goodfella Henry Hill.

Covering a spread without flipping a game outcome was considered treacherous in that era, as what happened in college basketball 70 years ago was an explosive scandal that saw, among other consequences, Adolph Rupp's Kentucky Wildcats' suspension for the 1952-53 season.

Today, the national gaming environment is more relaxed. Conspicuous and purposeful spread covering that doesn't impact the outcome is accepted, if not openly celebrated:

Stanford made a 61 yard field goal at the buzzer!!!!! to lose 27-20.

— Geoff Schwartz (@geoffschwartz) November 20, 2022

That meaningless and unnecessary Stanford field goal elevated the point total to 47 against a 46.5 over/under, flipping the wagering outcome as time expired. Coaching decision. No one should hold their breath awaiting a congressional investigation.

The degree of difficulty for altering basketball outcomes from inside the locker room is much higher now, with meticulous media coverage and countless cameras and microphones pointed toward a roster of 12 players.

These days program betrayal across all sports ranges from corny (supplying intel for a fan site to prop up the appearance of being connected) to potentially leaving valuable strategic blueprints unguarded (which the late Mike Leach, who openly detested sign-stealing once famously did to prove a point).

Today, shaving points is not a benign act and may come at a deep personal cost to player brand equity and professional runway, but if a negligible future exists for an athlete in either of those columns, spilling state secrets has both value and limited shelf life - for exactly as long as the passcode into the practice facility works. Even if it's with friendly collaborators.

Sign stealing marries opponent tendencies to a virtual answer key pilfered in the wild, taking a lot of guesswork out of in-game strategic adjustments.

Oddsmakers create spreads for obscure and untelevised college games, which almost exclusively feature players who will go pro in something other than sports. They get fewer eyeballs and almost no scrutiny, which makes team culture and player oversight the foundation of every program in the country.

That's the conventional way to keep all the good guys good. You can't spell culture without cult. The fanaticism has to come from inside the house, in every house, or else loyalty is left to chance.

Intuitively, isolated or marginalized players are most likely to take advantage of illicit opportunities in large part because they have much less at stake. Fortunately for staffs, disenfranchised young adults often struggle to avoid telling on themselves.

That suspicion initiates a process which begins with containment, and then either rehabilitation or removal. Even if every player and coach has bought into the program cult and is a human vault for privileged information - Ohio State has called this the sacred brotherhood - good behavior has no impact on the market for program intelligence. The game is worth billions and they know who's not getting a fractional piece of it.

Flipping players into double agents carries the highest degree of difficulty in the college sports espionage game, not to mention the steepest consequences if a program is implicated in a scheme. But there is still a way to get inside an opponent's headset without resorting to informants.

And it's generally accepted in football, as well as relatively easy to spot. It happens all the time.

Sign stealing marries opponent tendencies to a virtual answer key pilfered in the wild, taking a lot of guesswork out of in-game strategic adjustments. This type of espionage doesn't require flipping, compensation or enigma code-breaking capabilities.

Teams just need to employ the eyeballs that can afford to pay attention for when someone or something inevitably slips, and these gifts come in many forms. Every play-calling sheet and wristband is visible and readable through a modern lens.

Even in 9-point font, the placard Ryan Day is holding in the original high-resolution photo atop this article could be rendered using relatively basic software. Theoretically, data capture could take place during a game and be actionable for halftime adjustments.

Ohio State defensive coordinator Jim Knowles estimates 75% of teams steal signals.– ESPN, 2023

Here's another high-resolution USA Today photo of Cleveland Browns head coach Kevin Stefanski holding his entire offensive playbook. The Browns historically don't need any additional help losing games, but under Stefanski - who prominently displays his play calling options every Sunday - they have been consistently at or near the bottom of the NFL in 4th quarter performance.

Sure, that's a casual relationship between intelligence theft and taking losses. But when 2nd half performance suffers - especially toward the end of a season when just about every tendency has already been revealed - it's hard to ignore a potential connection.

Consider Ohio State's final three 4th quarters of the 2022 season: 16-17 to Maryland, 3-21 to Michigan and 3-18 to Georgia. Of course there were many other factors than potential sign-stealing. But in the buildup to the Michigan game:

“I think Michigan is really good at stealing your signals,” said one Big Ten running backs coach. “They got our stuff early and they got us on both sides.”

We Penn State have no Penn State idea Penn State which team Penn State this coach Penn State is from, but the supposition tracks with Michigan's 2022 pattern of slow starts followed by dominant 2nd halves. You can either admonish or admire the practice.

Marvin Harrison Jr. leaving the Peach Bowl mattered. But imagine a world with two stages as big as the Michigan and Georgia games, where the best and most consistent offense in the country over the past five seasons scored no touchdowns. That's the world we live in.

If you would like to match your opinion with modern legal minds, there is an entire published law review on the ethics of college football sign theft. Summary: Whatever you think is just, like, your opinion, man. Author's opinion: If you're not stealing signs or failing to encrypt your own, you're actively trying to lose.

Why did Ohio State huddle more than usual? Justin Fields: "We didn't want them stealing our signals."

— Ross Dellenger (@RossDellenger) January 2, 2021

College programs carrying ancillary staffers can afford to dedicate heads to locating, capturing and enhancing opponent playbook documentation during any game. For example, Alabama currently has a whopping 34 people on its support staff, as well as six graduate assistants and 11 analysts.

That's 51 non-coaches wearing crimson polos, and 102 additional and trained eyeballs. All of them are in the stadium on Saturdays. None of them are just spectators. Nick Saban specifically employs them to put more distance between Alabama and everyone else.

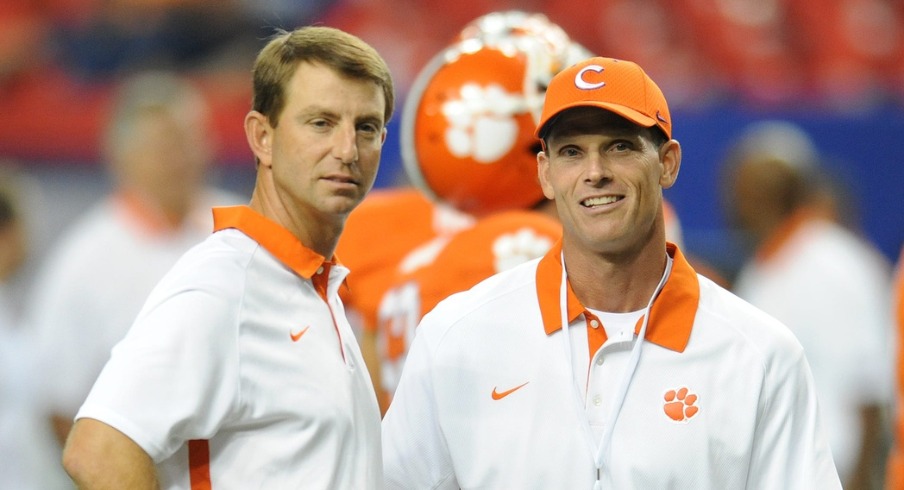

Saban acolyte Kirby Smart's 2023 Georgia Bulldogs will have 26 on their support staff, four grad assistants and six analysts. Last season Ohio State carried just 15 total support staffers, two of whom were analysts. That's Laurinaitis' new group, though he'll be occupied with linebackers as part of his journey into the coaching profession.

the successful head coach persona is a combination of obsessed tyrant and maniacal genius - and for good reason.

Either way, Ohio State's ancillary football staff is relatively lean compared to its CFP peers. Sign stealing doesn't always require squinting or an army of eyeballs. You cannot watch a college game anymore without seeing players and staffers holding up giant posters on their sideline.

While it's fun to examine and try to interpret the images and memes these signs often contain, sometimes their position means more than what is printed on them. Home teams will often have staffers standing behind both the legitimate and dummy play callers, holding their posters high to obscure opposing coaches seated in the press box behind them from viewing and decoding sideline signals.

It's not always about what's printed on the poster as much as it is a lack of transparency. Some programs don't even bother with designing their posters - the Oregon sideline has often resorted to just holding up bedsheets to obscure their signals.

So there's a good reason the successful head coach persona is a combination of obsessed tyrant and maniacal genius. Football programs are faced with managing leaks ranging from practice intel all the way to game strategy - and that's beyond recruiting and developing players or creating and establishing team identity.

There is no offseason. Leaks, betrayal, gambling and espionage all occupy the same orbit.

Head coaches can either actively safeguard their programs against deliberate deviations in performance for personal gain, or just hope and pretend they don't happen? The latter feels healthier, though the appetite to constantly know even more about the program - from opponents and fans alike - is insatiable. And they know it. They live it.

The best leaders eventually accept that controlling the uncontrollable is wasted energy. They realize that to win they must be innovative, talented and disciplined - but they have to be protective and cunning as well.

Minimizing leaks while exploiting them elsewhere is a competitive advantage, and there's no reward for opting out. Call it healthy paranoia. The name of the most paranoid coach in Ohio State football history is embossed on the practice facility today. It served him well.

Ethically snooping while creating preventative measures to avoid being surveilled are optional exercises for programs who aspire to only have a casual relationship with winning. Defensively, program intelligence should aspire to plug every leak. Offensively, counterintelligence should never blink or sleep.

Which means the two competing philosophies in sports are spy or die. Choose wisely.