The NCAA is holding its annual conclave this week, and the organization has been given a mandate of change (or else) by its power members. While the NCAA has shown more willingness to adapt than in the past, the Ed O'Bannon lawsuit still looms ominously overhead.

It appears the NCAA has taken another hit: today a report by sport management professor Dr. Daniel Rascher was filed on behalf of the plaintiffs in the O'Bannon suit, and the picture it paints isn't very kind to the old NCAA argument "we'd love to pay our players but unfortunately that'd bankrupt us." Apparently the money is already there.

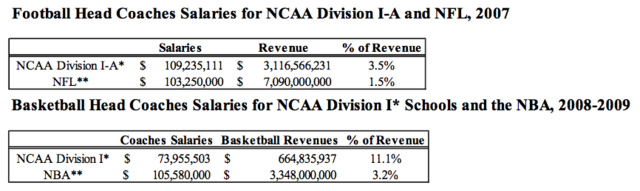

Here's the raw data:

That's not a good look for an amateur sports organization. But what about all those reports about athletic departments losing hand-over-fist? Well, Dr. Daniel Rascher filed a separate report on that very issue as well. Turns out, there's some fuzzy math and accounting magic going on. Among the tricks used by athletic departments to hide their profits.

- Not counting donations unless they're specifically made to that program.

- Not counting university-branded merchandise.

- Not counting a successful program's effect on applications, enrollment, and tuition.

- Undervaluing concessions, parking, and team merchandise.

- Overvaluing the cost of food, tuition, books, and room and board.

As Deadspin notes, these tactics have been around since a famous 1992 study centering on Western Kentucky's athletic department. The Hilltoppers claimed a loss of $1.5 million but were actually turning a profit in excess of $5 million.

Rascher also noted to Deadspin he doesn't believe this fuzzy accounting is malacious; it's not as if these universities are "for profit" after all, but there's definitely some exceptions:

Rascher notes that the athletics department at Texas counts among its expenses out-of-state tuition for every single athlete, whether they're actually from out of state or not. That's more money going from athletics to the school's bursar than is necessary—"an obvious attempt to falsely increase expenses," Rascher says. Why? Smaller programs might exaggerate expenses to receive more funding. But, Rascher says, it works the other way around too: "Really well-off athletic departments find ways to pay the rest of campus so everyone is fine with them doing their thing."

Rascher's full work can be found below, but the O'Bannon case definitely just got more interesting.