While not scouting the rest of the field in advance of the US Men's National Team's inevitable run to take home the World Cup recently, I've found myself getting lost in the mass of old Ohio State games uploaded to youtube. For those that haven't checked them out, I recommend doing so outside work hours as your productivity will grind to a screeching halt.

The list of great games is nearly endless, featuring classic Rose Bowls, rivalry games, and record setting performances that had gone unseen by generations. Undoubtedly, one of the great things about College Football are the legends that get created and passed down within each fan base. Within the great state of Ohio, few are bigger than the man who immortalized the number 27.

The star of one of the finest collections of talent ever assembled in Columbus, Eddie George was the workhorse and centerpiece of a team that went 11-1 in the regular season, winning the Heisman Trophy along the way.

While this record-breaking season is often represented by his 61 yard run against Notre Dame, immortalized in various photos and signs throughout the campus, his greatest performance came November 11, 1995 in the Horseshoe against the University of Illinois. Facing a defense featuring All-Americans Kevin Hardy and Simeon Rice, George rumbled for 314 yards on 36 carries, shattering the previous single game school record by 40 yards.

For those of us old enough to remember this game, we probably remember exactly where we were that day. While I recalled the images of Eddie out-running Illini defenders and that mauling offensive line, I hadn't watched the clips in depth until this past weekend.

This game is now 19 years old, and strategies on both sides of the ball have advanced greatly in that time. But what struck me was the simplicity with which that offense was so effective.

Eddie George carried the ball 36 times that day, yet did so while basically running only 4 plays. The offense was without their second best weapon that day, wide receiver Terry Glenn, who often acted as the deep threat in the passing game to keep defensive backs out of the running game.

How were they so effective? The easy answer is talent. As the old saying goes, "Jimmys and Joes beat Xs and Os," and the Buckeyes were running behind a line anchored by one of the best blockers in the history of the game. But as Ross and I have discussed on this site many times, the constraint theory of offense once again shined through on this day. The Buckeyes used complimentary concepts over and over to keep the Illini from over-playing any specific play, staying unpredictable while still only running a handful of calls.

I-Formation

For many years, the I-formation was the definition of Buckeye football. Lining a big running back behind an even bigger Fullback, who hit defenses square in the mouth.

While the Buckeyes did run the "Lead-Iso" play a few times this day, it wasn't really that effective. So, offensive coordinator Walt Harris called on two other concepts that took advantage of fullback Nicky Sualua's talents.

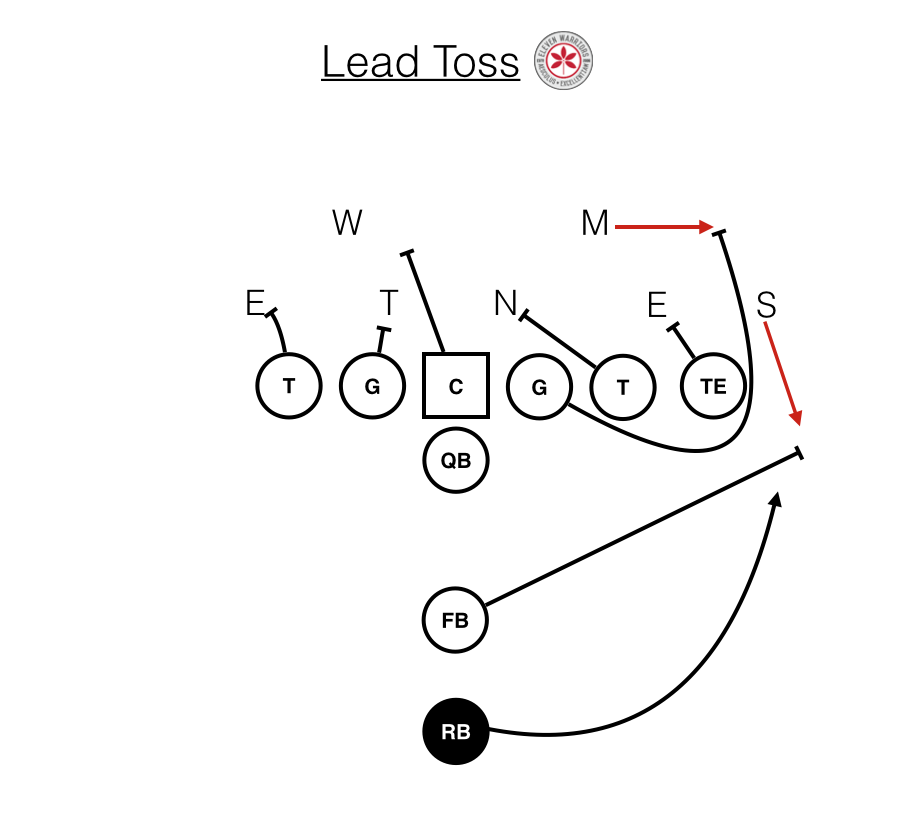

Few plays were more effective that year than the lead toss (this was the same play that sprung George for that famous run against Notre Dame). The basic concept of the play is very similar to that of the "Power" play run roughly 4,000 times by the Tressel era Buckeyes, and still seen often today. The Fullback kicks out the first defender that comes upfield, and the frontside guard pulls and leads the back through the hole.

The biggest difference between the lead toss and power though, comes at the aiming point of the play. In Power, the running back aims for the outside hip of the tackle, whereas on the toss, the back is looking to get further outside. Pulling a guard from the backside wouldn't allow enough time to get him in front of the ball carrier, so they must get that extra blocker from the frontside of the formation.

The easiest way to stop the lead toss is to get edge rushers upfield quickly, and have more defenders at that point of attack. Additionally, the Buckeyes often threw from the I formation quite a bit, so defensive ends like the aforementioned Rice were doing everything they could to get upfield and outside their defenders.

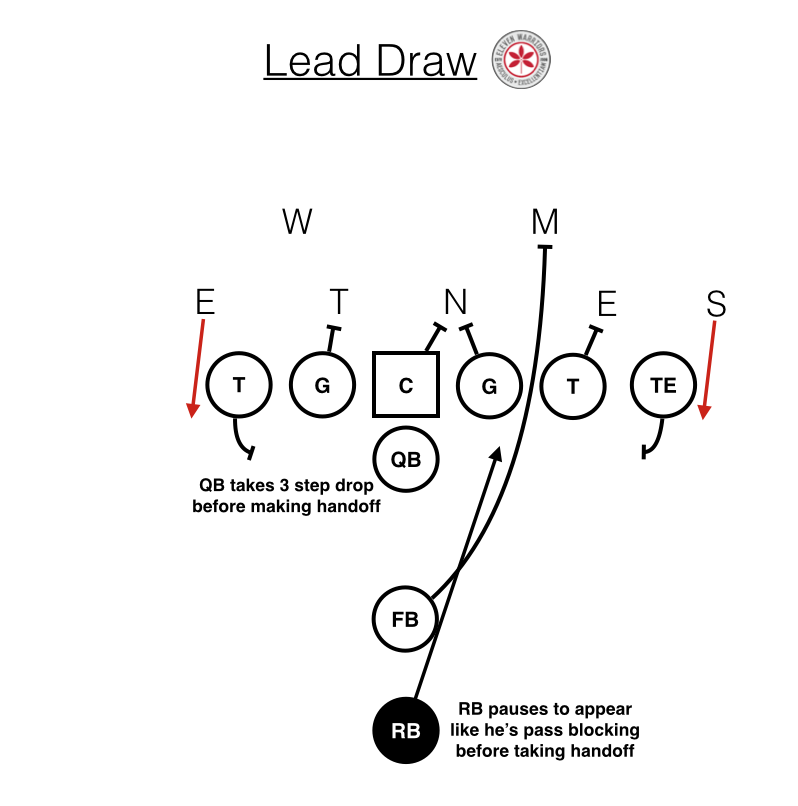

That's where the lead draw came into play. One of the oldest plays in football, the lead draw tricks defenses into appearing that it's a pass play, allowing defenses to come upfield and take themselves out of a run play before it's even truly begun.

Linebackers are taught to read the blocking patterns of the offensive linemen in front of them:

- If they step towards you, it's a run

- If they pull, follow them because the ball will follow

- If they step backwards, they're pass blocking

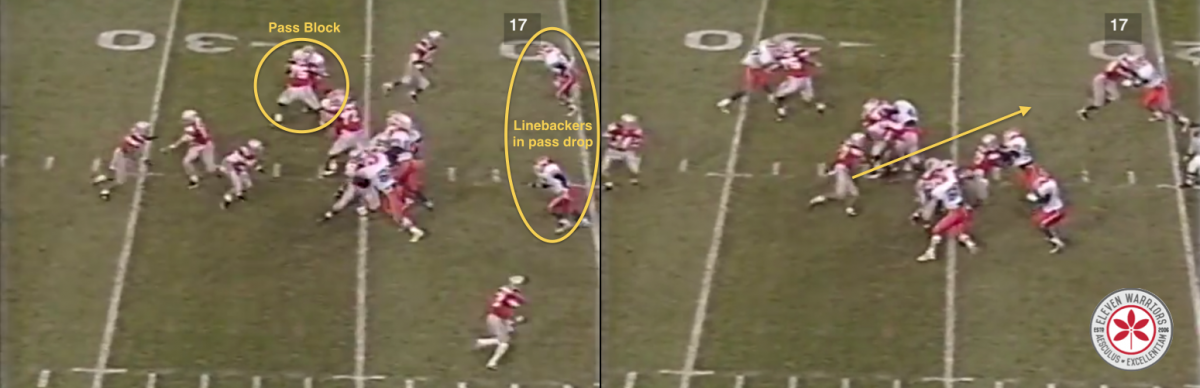

The Lead Draw breaks the third rule, as the entire offense appears to be creating a pocket for the quarterback to throw. Yet just as the QB makes his drop, he hands the ball off to his running back, who also happens to have a lead blocker right in front of him.

The runner must have great vision to execute the play properly, as the line will use the defenses aggression against them, and the same hole will not open twice. The rules for the back are very similar to today's zone schemes, where the runner must have patience before making a cut upfield once a hole opens.

Ace Wing Formation

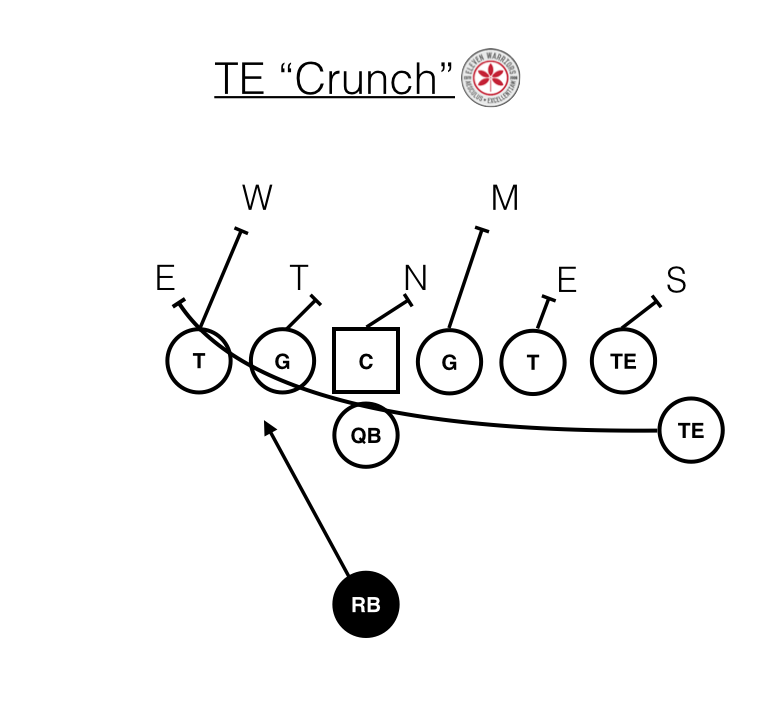

While the Buckeyes of this era were often defined by the I, they ran the ball from the "Ace" or single-back formation quite frequently. By stacking up star tight end Rickey Dudley behind a second tight end to the same side, the Buckeyes now had an advantage to one side, as they created a numbers mismatch. What they ran in this situation though might not look like anything special now, but was certainly novel at the time.

At the same time Eddie George was carving up defenses on the collegiate level, a rookie in Denver was doing the same to defenders in the NFL. Terrell Davis was the first in a long line of running backs to benefit from Mike Shanahan and Alex Gibbs' zone blocking schemes, which changed the way offenses run the football.

Until the "stretch" came along, the best way to run the ball outside was to run a toss sweep like the one above, pulling linemen and declaring your intentions along the way. The stretch changed things for defenses though, as runners were looking to cutback against defenders that were too aggressive and overran the play.

On this, Eddie's most famous run that day, center Juan Porter actually misses his block. But the strength and talent of #27 allowed him to break the tackle before going untouched the rest of the way. While allowing a defender to come virtually unblocked into the backfield is never a good thing, it slowed down George just enough to allow the rest of the Illini defense to overrun the play, creating a natural cutback lane.

In order to keep the defense from overloading the strong side of the formation, Harris often brought Dudley back across the formation to as a lead blocker. This concept should look familiar, as Urban Meyer's squad often uses the same principle with tight end Jeff Heuerman.

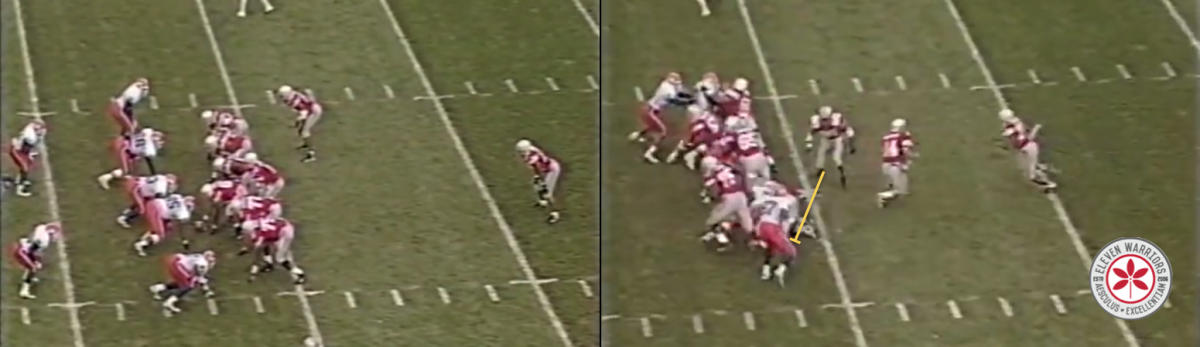

To the linebackers, the Buckeye offensive line appeared to be blocking towards the strength of the formation, as they would in stretch. However, instead of trying to eventually create a hole outside, they were simply creating a wall of blockers to the backside of the formation, with Orlando Pace as the cornerstone.

Yet it appears that the Buckeyes have left Illini star Simeon Rice unblocked. While his eyes are squarely on George in the backfield, Rice is met by Dudley, who has the momentum and leverage to kick out the end and create a hole for his star running back.

Watching the way Eddie George and the 1995 Buckeyes run all over Illinois that day reminded me of a recent quote from Eagles coach Chip Kelly:

Trends go one way and the other. I said this a long time ago, if you weren't in the room with Amos Alonzo Stagg and Knute Rockne when they invented this game, you stole it from somebody else. Any coach is going to learn from other people and see how they can implement it in their system. Anything you do has to be personnel driven. You have to adapt to the personnel you have. There's a lot of great offenses out there, but does it fit with the personnel you have. The key is making sure what you're doing is giving your people a chance to be successful.

While some of us wish the Buckeyes would return to the days of "smashmouth" football with big powerful fullbacks, the current version of Ohio State football isn't all that different. While the current iteration has more window dressing in the form of shotgun formations, option handoffs, and multiple receivers in place of a fullback, the basic philosophies are still very similar.

But Eddie George and the '95 Buckeyes aren't legends because of great play-calling. Schemes are a means to an end, and should be based entirely around who is running them. Walt Harris did a great job putting this team in a position to succeed, which more than often, they did.