She still remembers the bullets.

Not them whizzing through the house. Not the thunder of the gunshots themselves. Those only exist in her imagination. The same haunting imagination that pictured those bullets crashing like lightning through the window in the front of their home. The same imagination that saw them careening toward her son.

“‘Oh my gosh. They’re shooting at my child.’”

That was Lakeesha Hayes-Winfield’s first thought.

She was in a Zoom meeting for one of her two jobs when she saw her son, the second-oldest of her three boys, sprinting into the house.

“Get down! They shooting!”

That’s what TreVeyon Henderson yelled when he busted through the front door.

Adrenaline pumping through her, she did what TreVeyon told her to do. She got down.

She remembers, in that moment, a car riding by the front of the house. That’s what made it more terrifying and more sobering. More real.

Henderson had been outside washing his maroon Lincoln MKX, a gift from his mom, when he heard the gunfire ring out and echo from down the street.

“I guess he felt like the gunshots were coming towards us so he dropped everything and ran in,” Hayes-Winfield said.

They soon found out that the shots were coming from the block over. Doesn’t matter. They came from close by, enough to send a scare through their home.

“That car was just riding by, but I’m shaking and scared because I’m thinking they’re shooting and they’re shooting at him,” Hayes-Winfield said. “It was a street over, but stuff like that it’s still scary.”

That's not a memory from four or five years ago. The details weren’t fuzzy. It happened in December. And it’s not the only time she’s felt nervous for her kids while living in Hopewell, Virginia.

Multiple shootings, robberies and other forms of violence, in conjunction with the year-long pandemic leading to more crime in the area, have had crimes in Hopewell on the news or in the newspapers “almost every day,” Hayes-Winfield says, despite the fact that it’s a small city of less than 23,000.

“Sometimes I’m just like, I can’t wait until I can move myself off my street because I live in an all right neighborhood. But it’s getting bad out here,” Hayes-Winfield said. “Sometimes I have to tell my (youngest) son (Kesean Henderson) to not play in front of the window, and I shouldn’t have to do that.

“There’s been shootings a street or two over. Not really on my street, but close to home. That’s looking out my window where somebody had gotten shot a street over.”

When TreVeyon and Kesean were kids, their mom would not let them walk on the streets. And with how bad crime has been getting in the area, she says, she tells her kids that if they want to go somewhere – even to a friend’s house – that she will drive them there. Her oldest son, Ronnie Walker Jr., wasn’t allowed to walk across the street to go to the store until he was 16.

“I didn’t really even want him to do it then; he just did it, and I got really mad because you could be somewhere and someone just do a drive-by,” Hayes-Winfield said. “Just be shooting just to shoot because they have nothing better to do.”

Growing up in Hopewell taught me a lot....Im just blessed that Ill be able to make it out......Mannnnnnn, when you from a City like ours, this hits HARD!....Many from Hopewell dont make it out & BRUH MADE IT OUT!!!!.... https://t.co/M8Pved4dAQ

— Brother To The Night (@Just_MrDoctor) December 17, 2020

Hayes-Winfield says that despite it getting rough over the past year or two, she still loves what she calls “my city.” She was born and raised here. She has family and friends here. This is still home.

But she fears for her kids that they might be around shootings or robberies, and it got even harder this summer with an uptick in crime.

“It’s definitely been crazy,” TreVeyon told Eleven Warriors in late June. “There’s been a lot of stuff going on with the police and the killings. You just gotta be aware of your surroundings; be aware of where you’re at. Because it’s crazy out here. You never know what somebody’s true intentions are, and you never know when it’s your time to go.”

All of these anecdotes, all of these worries, they all lead to the greater point of this story. Of their family’s story.

“I just wanted my boys to grow up and do something with their lives”

If not for their mom’s efforts to keep them away from a life going down that path and if not for special, natural athletic and academic talents and strong work ethics from Lakeesha’s three boys, things may have turned out quite different for...

- Ronnie Walker Jr. – A two-year scholarship running back at Indiana who played in 22 games before he transferred to his home state to play for the Virginia Cavaliers.

- TreVeyon Henderson – One of the most-anticipated running back recruits in Ohio State history, one who has the potential to be a true freshman starter for a national championship contender and has a ceiling as an eventual first-round NFL draft pick.

- Kesean Henderson – A freshman running back/linebacker in the class of 2024 who played on Hopewell’s junior varsity team as an eighth-grader and who already has Virginia knocking on the door with a scholarship offer.

We’ll start with sports before we get to schooling. Both are equally important, but it all began with the former.

Seeing the violence around them growing up and seeing how easily people could go down the wrong path had the boys’ mom setting out to make sure they wouldn’t become negative statistics.

“Hopewell is a small city, and everyone I grew up with is either in the streets or in jail,” TreVeyon said. “We definitely grew up rough. We can’t afford the things everyone else can afford. It was very rough growing up. You’ll have a lot of people trying to bring you down. Once they see you trying to make it out, you’re gonna have a lot of people hating on you, trying to bring you down and things like that.

“My mom’s motivation is just to raise us into great men and make sure that we get out of here and don’t end up in the streets. She wants us to do something with our lives and not end up in the streets. Because that’s where most people end up from around here – the streets – because they feel like they can’t make it out. Some people think sports is the only way they can make it out.”

Sports was eventually the avenue out for Ronnie and TreVeyon, and it may someday soon be for Kesean, though his story is really just starting. But it’s not as if Lakeesha had some sort of master vision for that to be the case.

“I had three boys, so I just had to think,” she says before pausing. “I just didn’t want them to be running the streets. So I had to keep them busy, not knowing that it would pay off one day.”

It started with soccer when they were young kids. Eventually they all began playing basketball and football, too, but soccer was Ronnie’s first love. He wasn’t really interested in football at first as a 9-year-old. But that infatuation slowly grew, and when TreVeyon saw his older half-brother get more into the sport, he followed suit.

He wasn’t much a fan of playing flag football beginning as a 6-year-old, his mom says.

“But he was finally able to play in pads, and when I put him in pads he was really good then,” she says.

Sounds about right.

“Since I first started playing, I’ve been rushing for over 20 touchdowns and over 1,000 yards,” TreVeyon says. “I did that, like, every year.”

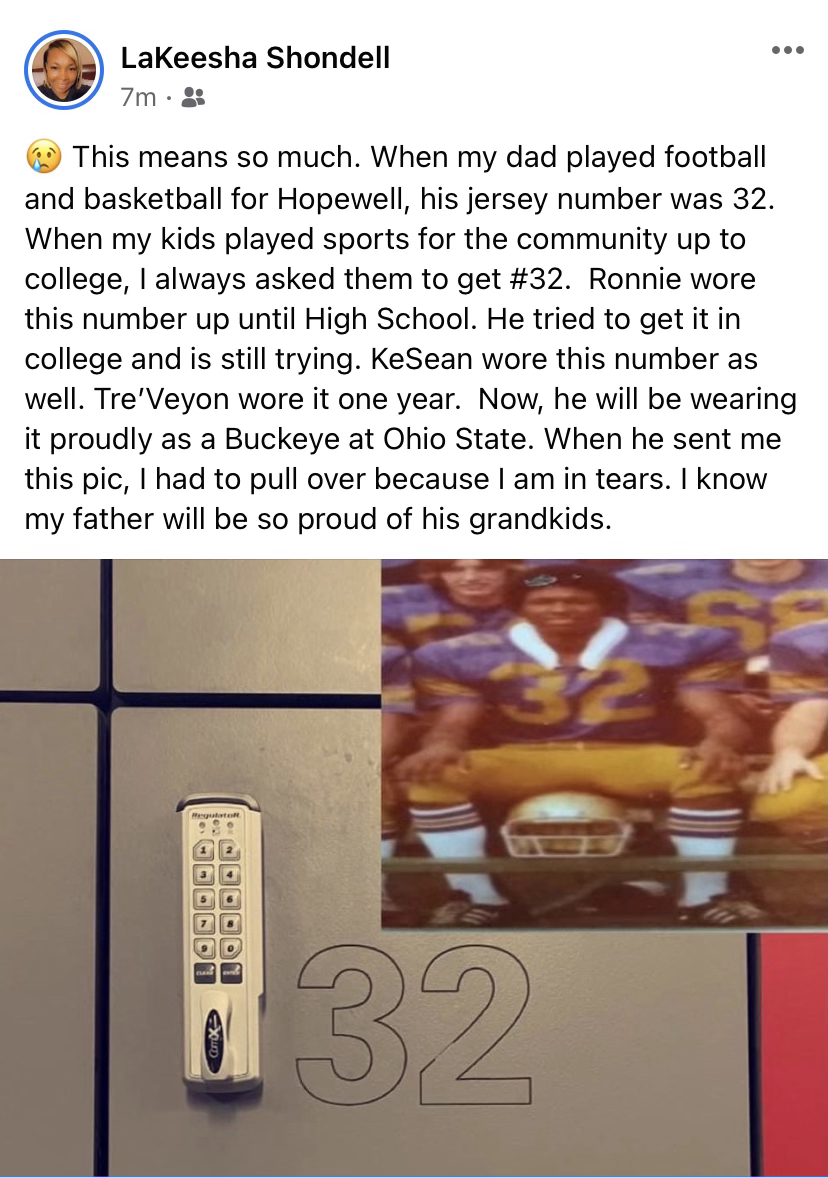

His inspiration for always gravitating toward running back is because of his grandfather Albert Lee Harris, Lakeesha’s father. Nicknamed “Airplane” because of the jets he flashed on the field, Harris was a football and basketball player at Hopewell who wore No. 32.

His grandson will be wearing that number as a freshman at Ohio State.

“When he sent me this pic, I had to pull over because I am in tears,” Hayes-Winfield wrote in a Facebook post, noting that Kesean wore the number as a freshman and Ronnie hopes to wear the number one day in college. “I know my father will be so proud of his grandkids.”

And not just because of football.

Incentive program

Hayes-Winfield never thought sports would be the ultimate thing that would lead to a better life for her kids.

“Football, you can only do for so long and can only do so much with it,” she says. “But with an education, you can do a whole lot.”

It has to be said, of course, that football is leading to a free education for her two oldest sons and looks like it could one day for her youngest. But when Ronnie first entered high school, it was all about the books.

She made sure of it.

Ronnie started making all A’s in eighth grade. So Lakeesha made a bet with him starting in ninth grade.

If you bring home all A’s for your report card, I’ll give you $100.

Easy money.

She couldn’t stop with just the first report card, though. Every report card in which he brought home all A’s, she dished out $100 to him.

“And I’ll tell you,” she says with a laugh, “he made all A’s from ninth grade all the way to 12th grade.”

TreVeyon and Kesean were honor-roll students, too, but she wasn’t giving them $100 yet. Once TreVeyon started finding out about the $100 big bro was getting, he started grinding a bit harder and made all A’s. She wasn’t aware just how effective this incentive program would be.

“And I’m like, ‘Dang. I’ve gotta come up with $200,’” mom said, followed by a laugh characterized with perhaps a tinge of pain. “It was so funny, but they kept it up. Tre would be like, ‘mom, my report card’s coming up, and I got straight A’s. You better have that money ready.’”

It all appears to have worked. TreVeyon was a 4.0 student at Hopewell whose last B came in middle school, and Ronnie was an Academic All-Big Ten honoree in 2019.

“I just wanted my boys to grow up and do something with their lives,” she says. “I wanted them to all go to college. That’s one of my goals and dreams is to have all three of my kids in college, get a great education, get a degree and pursue their goals and dreams whatever they decide. I do want all three of my kids to go to school because that’s very important to me. That’s No. 1.”

“She’s the type that’ll go broke just to get us what we want”

As a single mom, Lakeesha worked two jobs, which helped a bit in paying for their straight-A’s deal. That included a six- or seven-month stretch last year working two jobs. Often, she would have to wake up at 6:30 a.m. and work her first job before heading to the second for a 6 p.m. – 2:30 a.m. shift.

“A lot of people didn’t know I had a second job because I didn’t tell nobody,” she says. “I just didn’t want them out in the streets. I wanted better for them. I wanted my kids to be better than me.

“I just didn’t want my kids to feel like they had to go out in the streets and do things the wrong ways. Because they had their friends that were in their lives but ended up going a different route. I’d see stuff like that and tried my hardest to do what I had to do so my kids wouldn’t have to go that route.”

That work didn’t just help with the dollars for no Ds deal they had. It also helped in getting TreVeyon stuff like the new pairs of Jordans that would hit the Nike stores. She would have to leave work just to put tickets in at the store because, in a bit of a lottery-type system, you couldn’t get the new Jordans unless you got your ticket pulled because they would be in such high demand.

“She used to work two jobs just to help provide for us,” TreVeyon said. “I mean, she was raising three of us at one time, and we’re all boys. So you can just imagine what that’s like. She’s the type that’ll go broke just to get us what we want. We’ll always have a new pair of shoes and have some fresh clothes. And she’ll go broke just to do that. Most people think like, ‘Oh, we’re rich,’ because we’ve got on a new pair of Js and things like that. But they never understood the story behind how we got those.”

When hearing that, it’s hard not to think of the Kid Cudi line, On Christmas time, my mom Christmas grind. Got me most of what I wanted, how’d you do it, mom?

“Like he said, there were times I’d be at my last, but I made a way,” Lakeesha said. “I made ways by working extra hours or whatever to give them what they needed and wanted.”

That’s why she says she cried for “a whole year” once her oldest left the house to be a Hoosier. And it’s why she did the same on the night that TreVeyon became a Buckeye, committing to Ohio State while on the phone with Tony Alford in late March.

All those years of sacrifices seemed to make her weightless in that moment. All those years of hoping she would get them out of Hopewell made her weak.

“I cried and held him when he committed because I think it finally hit me, and I cried like a baby,” she said.

TreVeyon is a mama’s boy, Lakeesha says, and it’s clear how similar the two are. The same laugh, same mannerisms. The way they both say “Oooh yeah” or “Yuuup.” It all comes through clear as crystal over the phone as soon as she speaks that yuuup, this is TreVeyon’s mom.

She’s always been the backbone for her three sons. It’s a common theme throughout their lives. Now, TreVeyon is starting his path to pay it back, moving into his Ohio State dorm three weekends ago and starting winter workouts in preparation to begin his Buckeye career this fall.

“That’s my No. 1 motivation is my mom – to get her out of Virginia so that she can live a great life and won’t have to stress anymore,” he says.

There is a banner that hangs on TreVeyon’s Twitter page that helps encapsulate all of this. And, hopefully, you now know at least a small part of the story behind the words:

My mother worked too hard for me not to be great.