And so, the off season continues apace. Sooner or later, it’ll have to be football season, but, until then, well. The Napoleonic Era continues as well, and, just as last week we talked about a variety of wars that were spawned in Scandinavia by the Treaty of Tilsit and the enforcement of the Continental System, this week we’ll see the start of the Peninsular War, another war started by the TIlsit and the Continental System.

France and Iberia

France and Spain had been allies since the Second Treaty of San Ildefonso in 1796, when Spain left the Second Coalition and joined up with France. However, the British victory of Trafalgar sent the alliance into something of a tailspin. Spain became more neutral in its position vis-à-vis France, and withdrew from the Continental System. Spain provided rather limited support for the variety of wars Napoleon fought between 1805 and 1807. However, his great victories in those campaigns convinced the infamously corrupt Spanish Prime Minister, Manuel de Godoy, that perhaps it was a good idea to back the strong horse, and he renewed the Spanish and French alliance.

Portugal had attempted to remain mostly neutral in the Revolutionary Wars, particularly after Spain allied with France. A short war with Spain in 1801 tended to reinforce this neutrality. However, Portugal still kept close ties with Great Britain. Portugal and England have the longest standing alliance in human history, starting in 1387 and continuing, without interruption, to this day through NATO. While Portugal was neutral in the wars, Portugal tended to look the other way when the British came into port. The Portuguese strengthened their position with the British after Trafalgar, welcoming British ships to Lisbon, allowing trade with Britain, both from Portugal and from Brazil, and taking other steps to work with the British. This cooperation continued even after Tilsit.

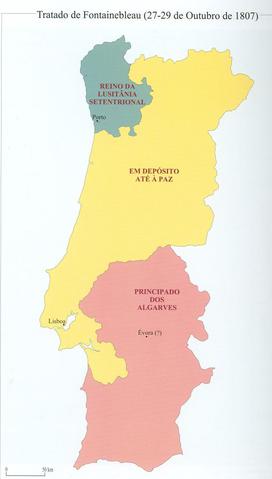

Napoleon decided that the time had come to settle Portugal’s fate. After negotiating Tilsit, he returned to Paris, and invited Spain’ Ambassador to come to Fountainebleau Palace to figure out what to do about Portugal. The subsequent secret Treaty of Fountainebleau, signed in 1807, proposed to divide Portugal into three parts. The northern part would be given to Charles Louis, the deposed King of Eturia, who had been dispossessed when Napoleon annexed the Kingdom. The middle part would be administered by the French Empire, for eventual annexation into France. The southern end would be made into the Principality of Algavares, and given to Manuel de Godoy to rule as a French client. The Kingdom of Spain itself would get nothing for its help, but Godoy didn’t care much- he was looking to promote himself out of the Spanish court.

Napoleon, of course, had some rather duplicitous plans for Spain after defeating Portugal, anyway- a lot of this was a pretext to march French troops into Spain, and to get the Spanish army away from its fortresses and garrisons, in preparation for the eventual overthrow of the Bourbons in Spain and their replacement with a Bonapartist King. However, that discussion is a bit more suited for a later time, since it’s complicated, and more related to the battle we’ll discuss nest week, Corunna.

The Invasion of Portugal

Diplomatic efforts to bring Portugal into the Continental System through the summer of 1807, which the Portuguese largely ignored. In response, Napoleon sent an army under Jean-Andoche Junot, a veteran of the French Revolutionary Wars that had worked his way up from private to general, and had been ambassador to Portugal for a time. Napoleon promised Junot promotion to full Marshal if he succeeded in taking Portugal. Junot left France in October, and on November 12th, crossed the border into Portugal, along with three columns of Spanish troops. Junot attacked down the Tagus River, leading to Lisbon, while the Spanish columns attacked at various other invasion routes into Portugal.

Napoleon urged Junot to hurry and get the thing done before the British could show up. Junot decided to rush down a poorly guarded- and maintained- road towards Lisbon, which strained his army’s supplies and morale. Still, the rushing movement of the French brought home to the Portuguese ruler, Prince John (ruling as regent for his insane mother, Queen Maria) that the French meant business, and it was time to make what peace he could. In the meantime, the British sent a squadron to Lisbon, and prepared to storm the harbor to burn the Portuguese fleet. Prince John ordered his diplomats to facilitate the French moving into Portugal at first. However, the commander of the British squadron of Lisbon showed Prince John a series of newspapers that declared Napoleon’s intention to depose John’s family. John decided to ask the British to bring him and his family to Brazil, and fled the country. Between him and all the people who fled with them, they took half the cash in Portugal to Brazil.

Junot’s efforts seemed like a success. With John fled, the road to Lisbon was open, and the city surrendered without a shot. Porto, the main city in the north, fell just as easily to the Spanish, and the only resistance crumbled once word of Lisbon’s fall spread. However, occupying Portugal was not easy. Junot broke up the Portuguese Army, sending home the junior soldiers and shipping the veterans off to garrison in the Confederation of the Rhine. The bureaucrats of Portugal were willing to work with him, but the general populace disliked their new French and Spanish overlords, rioting when the French flag rose over the palaces of Lisbon. This feeling only intensified when word came from Napoleon that Portugal would have to support not only its occupying garrison, but the troops that were taking over Spain as well. By January, 1808, Junot began executing tax resisters, leading to further trouble.

The spark that exploded the powder keg in Portugal came from Spain. We’ll discuss it more next week, but, on the 2nd of May, 1808, a riot broke out on Madrid, led and supported by the Spanish Royal Guard. This uprising spread across Spain, and, in early June, 1808, the Spanish garrisons abandoned Porto to go fight against the French. Junot was completely cut off from communication with France. He decided to concentrate his troops in Lisbon, which had the only store of arms in Portugal, and leave the rest of the country to its fate until he could get reinforcement.

The rebels managed to raise a series of motely militias that began to threaten the outlying towns near Lisbon, which Junot cleared away at the storming of Evora. However, in that attack, the French commander, Loison, killed every last man, woman and child inside the walls, ending any chance Junot had at a peaceful resolution to the rebellion. At about the same time, the British landed the expeditionary force that had been lurking on the coastline at Mondego Bay, where the local university students had tossed out the French garrison holding the fort. There, 15000 British troops under the command of Sir Arthur Wellesley, were organized.

Wellesley was young for the command, a year shy of forty. However, he was certainly the most experienced and talented general officer in the British Army in Europe in the era, with the possible exception of Sir John Moore, his eventual boss in Iberia. At 16, Wellesley entered the army, and rose quickly through the ranks to Colonel before the age of 30, largely on the back of the financial support of his brother, who allowed him to purchase his billets as quickly as they opened. He led troops in the Flanders Campaign of 1793-94, which, as we’ve seen, was something of a disaster for the British. After the campaign, his regiment shipped out to India, where it fought in the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War against the Tipu Sultan, where he organized the logistical efforts of the army as well as commanding several assaults in the campaign. Afterwards, he led the East India Company Army in the Second Anglo-Maratha War, winning the stunning victory of Assaye and forcing the Maratha to heel. After this war, he returned to Britain, commanding a wing of the expedition against Copenhagen in 1807.

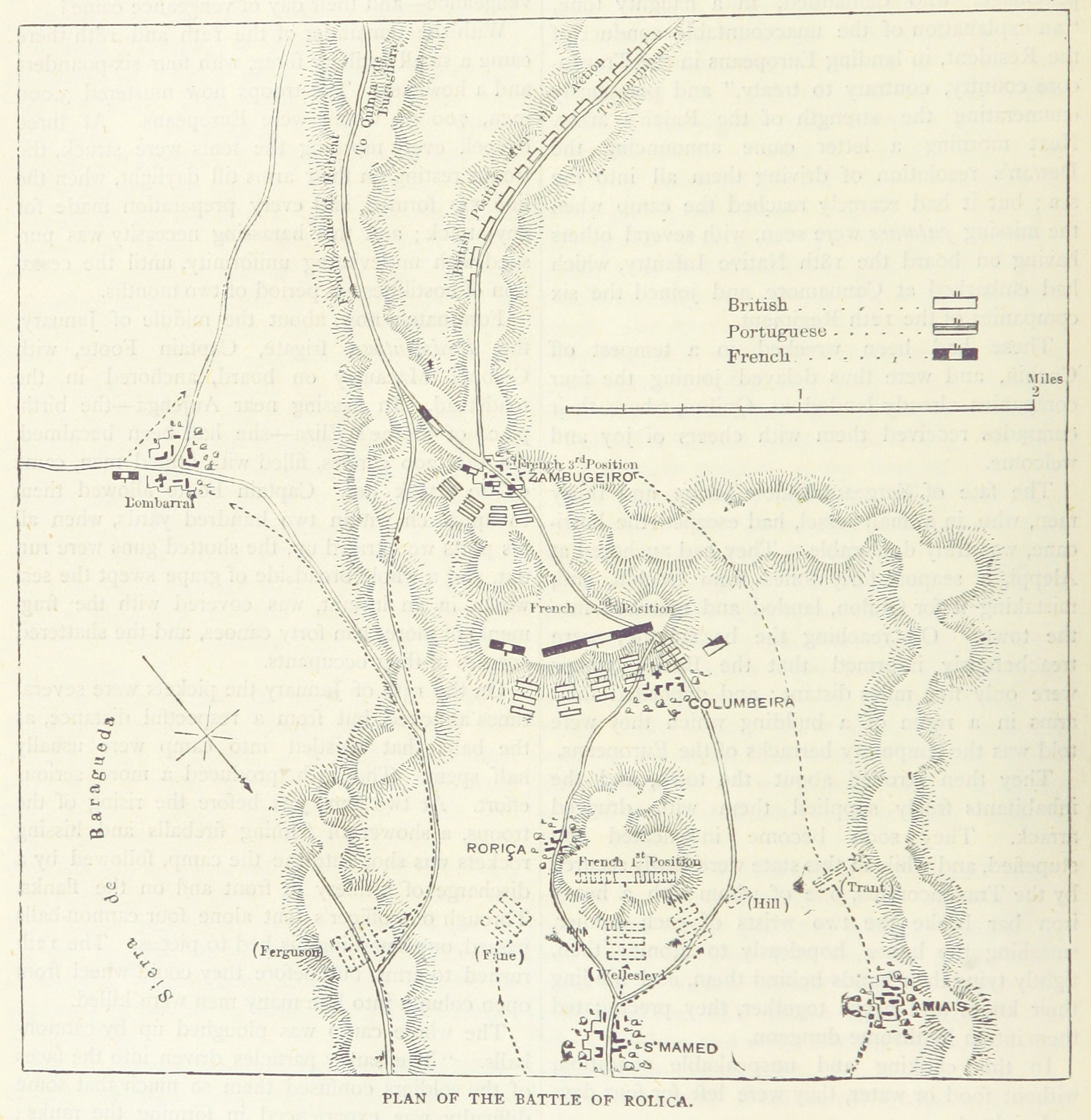

Wellesley moved quickly, marching south to Lisbon and Junot. His quick movements and good intelligence from his allies in Portugal allowed him to overwhelm a French detachment at the Battle of Rolicia on June 17th, 1808, clearing the way towards Lisbon.

After hearing of the progress of the British expedition, Junot, who didn’t want to get locked into a siege in Lisbon (Where a Russian Naval squadron was eating all his food), decided to march out to meet them. The British, meanwhile, had paused at the village of Vimerio, on the way to Lisbon, to reorganize and get their supplies in order. Once Wellesley heard of Junot’s approach, he decided to establish a defensive position on the hills outside of the town, and managed to induce Junot- who he outnumbered 20,000 to 15,000- to attack his defensive positions.

The Battle of Vimerio

As we’ve discussed before, the French had developed, based on their experience in the Revolutionary Wars, a tactical system that had worked quite well in the previous decade and a half. In short, the French attacked aggressively whenever possible. Attacks began with a bombardment, usually from a concentrated battery at the point of attack. Skirmishers, fighting in a loose order, went forward, to both screen the main attack from enemy fire and to harass enemy formations with constant fire. This fire inflicted casualties, cause frustration, hurt morale, and helped disorder the enemy. The main attack came in columns, driving into the enemy positon with the weight of mass and momentum, breaking through and preparing the way for further attacks.

This method was largely similar to the methods used by Indian troops to fight the British. The British East India Company had developed a variety of tactics to fight these efforts, and Wellesley brought them to Europe. We’ll see them unfold in this battle in particular.

Wellesley organized his army on the old standard, creating eight brigades of three to four battalions, all under his direct command. He deployed his army with three brigades to the front, along the ridges guarding the approaches to Vimerio, leaving a long ridge to his left unoccupied. These brigades deployed on the reverse slope of the hill- that is, behind the crest facing the French. The other five brigades, Wellesley left in reserve behind the hills. Conversely, Junot organized his men into an oversized corps, with two infantry divisions and a cavalry division, with a reserve brigade of grenadiers. Junot decided to pin the British on the hills to the south, then sweep over the northern ridge, around their flank and cut them off.

Junot organized the usual assault. However, with the British troops protected behind the crest of the ridgeline, the cannonade was not particularly effective, inflicting few casualties and allowing the British to keep good order. As the French sent their skirmishers forward, the British responded with their own. Each regiment kept a company of skirmishers- about 100 men, and the British army had two regiments of rifle armed skirmishers that went forward. Between the two forces, a fierce firefight developed, which the British- who had more and better skirmishers- got the better of.

Meanwhile, Junot’s army lost coordination. His flanking movement was slowed down by bad terrain, allowing Wellesley to move his reserve brigades to the north to take up defensive positions. Rather than wait for the slow flank attack to develop, he launched an assault into the main British position. The British skirmishers fired into the attacking French columns, which were too deep and narrow to fight back. Only their momentum carried them forward, and the skirmishers peeled back and away. The two uncoordinated French attacks continued up the hills. Once they closed to within a hundred yards or so, the British marched up to the top of the hills, and poured disciplined, rapid volleys into the attacking French columns. The British deployed in a double line, so that even when one attack drove off the first line, another stood to smash the attack. Faced with a failing attack across the line, Junot committed the grenadiers and cavalry into the center of the British position. These troops succeeded in gaining the town for a short time, but a determined counterattack after the British rallied, with the support of the British and Portuguese horse, drove the French from the field.

The battle left about 250 British dead, and 500 wounded. About 700 French died on the field, and another 1400 were wounded. Wellesley began organizing his pursuit of Junot, however, the day after the battle, Sir Hew Darymple, his nominal superior, took command. Darymple decided against pursuing Junot, and, instead, decided to negotiate an armistice. The Convention of Sintra allowed Junot to return to France with his baggage, arms and all the loot he could carry, conveyed home by the Royal Navy. The terms were so generous that all the British commanders, including Wellesley, were recalled to Britain for court martial. While they would be acquitted, only Wellesley was considered to have done well enough to stay in the army. Meanwhile, command in the Peninsula fell to Sir John Moore, who would have to face Napoleon’s invasion of Spain.

If you found this interesting, please feel free to comment below. If you want more of this sort of content, feel free check out the archive by clicking here.