Another week in the books for us, and another week closer to football. We’re also getting into the highlights of Napoleon’s military career- two weeks ago, we discussed Ulm, this week, Austerlitz- and it won’t be long until Jena and Friedland, either.

If you enjoy these topics, feel free to comment below. If you are new to the series, or need to catch up, check out our archive here.

Maneuvering to Austerlitz

After the Battle of Ulm, the Russian commander, Kutusov, began to retreat away from Bavaria. First, he maneuvered towards Vienna, but, after deciding he couldn’t hold the city, continued his retreat. As he retreated, he linked up with the remains of the Austrian army north of the Alps, and with Russian units mobilizing and marching to meet him. In the meantime, the Austrians, Russians and British pressured the Prussians to enter the war. While they had planned on joining the Coalition earlier in 1805, the balked in the summer. With the Austrians defeated, the Prussians decided to enter the affair, though, a bit late.

Napoleon’s pursuit of Kutusov yielded some initial successes. He crossed Bavaria and theTyrol, eventually taking Vienna and forcing the Austrian Imperial court to flee. However, despite the strength of its fortifications, Kutusov had cleaned out most of the supplies in the city for his army. This made Napoleon’s supply situation difficult- he had a large army to feed, he was far from friendly sources of supply, and the Russians were heading to the Carpathians. If Kutusov made the Carpathians, Napoleon would be deep in Hungary with little supply, trying to force a passage through the mountains as winter fell, and with a Prussian army ready to fall on his rear. Napoleon needed a battle.

Fortunately for Napoleon, one of the reinforcements Kutuzov had picked up was Tsar Alexander I, who would play a notable role in forcing the battle. Napoleon decided that he needed to convince the Russians to reverse their retreat, and that the best way to do that was to feign weakness. In late November, it wasn’t too hard for him to do that. His troops were spread out between Austerlitz and Vienna, with only about 50,000 men in the main body of his army. The Allied army had about 85,000 men, giving them quite an advantage- if it weren’t for the fact that 20,000 more French troops were only a couple of days away.

Napoleon played up this weakness. On November 25th, he sent an envoy to the Allied Army to sound out the Emperors about a negotiated peace. While there, the envoy got a good measure of the Allied Army for Napoleon. On the 27th, he had his army abandon Austerlitz and the Pratzen Heights outside the city, making sure to make the retreat look disorderly. The next day, he requested a personal audience with Alexander. While Alexander did not take this meeting, one of his more aggressive aides did, and came away from the meeting with the impression that Napoleon did not have the stomach for any serious fighting. As a result, Alexander overruled Kutusov, and demoted him from command of the army. The allies turned around, and maneuvered back to Austerlitz, arriving on December 1st.

The Battle of Austerlitz

Napoleon had suckered the Allies into a battle that he wanted, and, really, the Allies shouldn’t have wanted. However, his plan had not ended there. He decided to try and manipulate the Allies into an attack against his southern flank, the French right. This area included the main road back to Vienna. If the Allies crushed his right flank, they could cut the road to Vienna, and trap the French out of supply between the Allied and Prussian armies. However, unbeknownst to the Allies, Napoleon had successfully recalled the missing corps of Bernadotte and Mortier, placing them to reinforce the French left for the coming attack. Davout was also coming up from the south, and would be able to reinforce the French right over the course of the evening.

The Allied army formed up into eight divisions. Four infantry divisions, under Docturov, Langeron, Kollowrat, and Prezbyseszewski, and a cavalry division under Prince Lichtenstein, would attack the French right and move to cut off the French from Vienna. Another division, under Bagration, would hold the northern flank, while Prince Constantine would command the reserves near the center. The attack would go off first thing in the morning.

At about 0800, the Allies began their attack. The attacks were not particularly well coordinated between divisions, as there was no overall flank commander to coordinate their actions and movements. However, sheer weight of numbers and fire drove the French steadly back, even as Davout’s men arrived on the scene to slow the Allied attack. However, even as the attack succeeded and gained momentum, it pulled the main Allied army away from the Pratzen Height and Bagration’s force, creating a gap in the center- right where Napoleon intended to attack.

At 0900, Napoleon ordered a general attack. Lannes moved against Bagration’s units on the north, while Bernadotte attacked the center-left and Soult moved to support them. The attack on the center surprised the Allies. The only forces in the area were parts of the Langeron and Kollowrat divisions, again without an overall commander to coordinate them and their division commanders wrapped up in the attacks against Davout on the French right. Still, Russian commanders in the area hastily organized a defense of the Heights and the Allied center.

The attack proceeded as a typical French attack: a heavy bombardment against Allied troops, with skirmishers moving forward to harass the Allied formations and screen dense attacking columns. The French moved quickly, launching several attacks. While some of the initial attacks were repulsed by skillful local Allied commanders, the sheer weight of the French army couldn’t be denied. Bernadotte’s forces broke open the Allied center, separating the Allied northern and southern flanks.

To try to stabilize the situation, Constantine committed the Russian Imperial Guard from the reserve, which stopped Bernadotte’s attack. However, Napoleon countered with his own Guard, however, clearing the center. Meanwhile, in the north, Lannes pressed Bagration. Bagration held his ground, but with his left threatened by Bernadotte’s attack, he had no choice but to slowly retreat to the east as Lannes pressed.

By occupying the center, Napoleon could bring the weight of his main reserve, Soult’s corps, against Bagration in the north, Kollowrat’s retreating center, or Langeron’s attacking force in the south. Napoleon sent Murat, his heavy cavalry commander, against the Allied cavalry under Lichtenstein, who had maneuvered to support Bagaration as the center fell. Murat’s troops broke the Allied horse, and threatened Bagration enough to force him from the field in the mid-afternoon. Bernadotte kept up his pressure against Kollowrat, and Napoleon ordered Soult against Langeron’s flank, while ordering Davout to switch to the offensive. From 1400 to 1600, these forces squeezed down on the Russian southern flank, breaking it by the end of the afternoon and setting of a headlong flight. As those men fled, Kollowrat’s men broke, leaving only Bagration’s forces the only ones in good fighting order as they retreated.

The casualties were as lopsided as you might expect. The Allies suffered about 5000 killed and 10,000 wounded, with another 12,000 lost as prisoner. The French lost about 1300 dead and 7,000 wounded, with a few hundred captured.

The Treaty of Pressburg

Austerlitz ended the Third Coalition. After the battle, Francis of Austria sued for peace, and signed the Treaty of Pressburg on December 26th, 1805. In the Treaty, Austrian reaffirmed the Treaties of Campo Formio and Luneville. The Austrians also had to give up land to the Kingdoms of Bavaria, Baden and Wuertemburg. They also had to surrender Venice to the Kingdom of Italy, which Napoleon held. They also had to pay a 40,000,000 Franc indemnity.

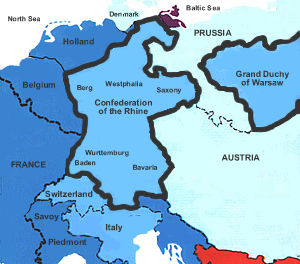

With Austria out of the war, both Austria and France made a series of moves in the German states. He formed the Confederation of the Rhine in the summer of 1806 from his various German Allies. He consolidated many of the smaller principalities by annexing them to larger kingdoms, giving him more control in the area and giving him stronger allies to call upon as the wars went on. As Napoleon continued his successes in 1806 and 1807, more and more states joined the Confederation in an effort to keep Napoleon from annexing them into the larger kingdoms. This did not stop all of the consolidation, but those who entered voluntarily at least gained some rights in reference to how the confederation was governed.

Given Napoleon’s growing power in Europe, Emperor Francis I of Russia decided to dissolve the Holy Roman Empire. Given he was about to turn 40, and with Europe in turmoil, he was concerned that he might not live longer. With most of the Electors of the Holy Roman Empire firmly in Napoleon’s pocket, Francis feared that his heir could not win the election- or that Napoleon would move to force Francis to abdicate the Holy Roman Empire in his favor. So, on August 6th, 1806, Francis abdicated the Holy Roman Imperial throne and formally dissolved all the oaths made to him by the members of the Empire, without naming an heir. This effectively ended the Holy Roman Empire, which had been founded by Charlemagne more than a thousand years previously. Of course, the HRE had been a largely empty title since 1648, and Francis’ main power lay in the Hapsburg Domains anyway. Still, this was a powerful symbol of the changing times in Europe.