Now that Army-Navy is behind us, we settle into the long- well, not that long, these days- period of waiting for the bowls to being. It seems like a good time for more military history, then. This week, we’ll look at the Battle of Wattignies, in which the French Revolutionary forces continued to refine their tactics as the French Revolution continued altering the military situation from the standard way of doing things.

Of course, it’s not as if the French Revolutionary government saw some big flaw in the military systems of the 1700s and moved to exploit them- they were in deep hole, and were trying to climb on out.

The Committee for Public Safety

As Dumouriez was stringing together victories and Valmy and Jemappes, conditions in France really hit the skids. The Constitution of 1791 was a fairly moderate one, with unicameral legislature elected by propertied men, a limited veto for the King of France, but with the rights listed in The Declaration of the Rights of Man guaranteed to the French. However, the Constitution was not nearly radical enough for the French radicals, particularly those of the Jacobin Club. The Jacobins called for more forceful reform, the elimination of the monarchy, land reforms, universal male suffrage, and a number of other major, radical reforms. They had enough power in the Assembly to make it difficult to run, and to propose legislation that would either not pass or would be vetoed.

The Jacobins also had a great deal of support amongst the urban poor, particularly in Paris. Conditions in France, particularly for the poor, and even more particularly, the urban poor, had continued to devolve ever since the Revolution began. Food prices were through the roof, in particular, as the farmers of France had a hard time producing food, and banditry in the countryside made transporting anything difficult. As they starved, the poor of Paris grew increasingly agitated. The Jacobins, in turn, pushed them increasingly towards violence- and, as the threat of violence grew, the Jacobins pushed a more radical agenda in the Legislature, which the King continued to veto.

The whole thing came to a head in August, 1792. The mob in Paris assaulted the palace where Louis XVI lived as a virtual prisoner. The Paris municipal government called for the end of the government, and a new constitution, followed by a number of other city governments. While Louis XVI survived, he was, for real this time, arrested, jailed and locked away. The moderates and monarchists in Paris fled the city, figuring London or Amsterdam looked like a good place to be. Those that didn’t escape were quickly rounded up and dragged off to prison, where they were executed in early September, cementing radical control in Paris, and over the French government. The radicals quickly moved to execute Louis in early 1793.

Meanwhile, of course, the war continued. In Flanders, Dumouriez, believing the Netherlands was ripe for a revolution, marched from the Austrian Netherlands into the Dutch Republic. However, he discovered rather quickly that no one in the Netherlands really wanted his help. The Dutch army linked up with a reinforcing Austrian Army, and quickly began to maneuver against Dumouriez. Dumouriez moved to invest Maasatrict, the first major fortress in his way, when the Austrians showed up. Knowing that his army would melt in a retreat, Dumouriez turned to face the Austrians at the Battle of Neerwinden. Dumouriez attempted to repeat his success at Jemmapes, using columns of enthusiastic soldiers to concentrate and assault the Austrian/Dutch line. However, this time, rather than holding a numbers advantage, the sides were mostly even. Enthusiasm proved no match for entrenched, disciplined fire, and the French forces broke. The Jacobin government sent a committee to investigate the loss of the battle, and the subsequent loss of the Austrian Netherlands. Dumourieiz, unwilling to be the next victim of the Radicals, defected to Austria- costing the French their only victorious commander.

The loss of Neerwidnen and Dumouriez was not the only setback for the French in 1793. The execution of the king lead to a Royalist revolt in the Vendee, along the coast of France. Controlling several ports, the rebels received arms and supplies from Britain, along with the occasional influx of troops from Britain and French exiles. Another royalist revolt seized the port of Toulon, the main French naval base on the Mediterranean. The Austrians launched another offensive in Italy, driving the French from Lombardy and Nice. The British entered the war, landing an army in the Netherlands and moving to besiege Dunkirk.

Once again, France stood poised on the edge of disaster. The Committee for Public Safety, which carried out the orders of Maximillian Robespierre, France’s effective dictator, took even more radical steps. The government forcibly seized food from the countryside (adding to the revolts), set price controls across all goods in France, instituted a summary justice system for those who opposed them, which the Jacobins dubbed the Reign of Terror, and, to rebuild the failing armies, instituted the Levee en Masse.

The Levee en Masse

Needing armies to fight on multiple fronts, in France and on the borders, and, realizing that the troops they could raise were not going to match the quality of the Austrians and British, the Committee for Public Safety went for complete numbers. On August 23rd, 1793, the Committee for Public Safety announce that every person in France was conscripted to support the army. Every man between 18 and 25 was to be inducted into the army. Older men would report for work in armament workshops to make weapons. Women would go to the front to provide medical support, or make bandages at home. The infirm would go from place to place to rally support for the war effort, reminding people of the suffering they had undergone to overthrow the monarchy, and the work they needed to do to preserve the Revolution.

Conscription wasn’t really anything new. The Romans, theoretically, could impress men in to service, but never had to- when the Romans had trouble filling the ranks, they just upped the recruiting pay. Many Germanic societies in the Middle Ages had agreements where groups of a few hundred households would need to provide a hundred men for a campaign, but this was only used as a militia. The Prussians and the Russians in the 1700s required towns to provide men for service. However, the incentives of military service- three hots and a cot, a nice uniform, regular pay and endless adventure- meant that there were no shortage of volunteers to meet the rather low quota. The most commonly coercive form of conscription before the Levee was the British Impressment system, where British sailors, longshoremen and merchantmen could be forcibly enlisted in the Royal Navy in times of war- though, even at the high point of impressment, impressed sailors never outnumbered volunteers for service. In fact, the Levee wasn’t the first conscription program by the Committee- they had called for a quota levee of 300,000 men in the spring of 1793.

The forcible enlistment of every many between 18 and 25, effectively without pay, was, quite simply, completely radical. No king could do it, for fear of a revolt against his rule for breaking a fundamental right of his subjects- nor could they pay that many, since the idea of not paying soldiers in 1700s Europe was too scary to mention, invoking fears of bandit-armies from the 30 Years War. Large armies also raised logistical concerns- how would you feed that many men, anyway? And what good would men be that were forced into service anyway? In an era that relied on professional soldiers, that in turn expected to be fed, paid and clothed, undisciplined, impressed men were less than useless.

Despite these challenges, the Committee for Public Safety’s conscription programs raised the size of the French armies from around 300,000 men at the beginning of 1793 to about 1,000,000 by the end of the year. Of course, once you have a million men in the army, it raises an important question: just what are you going to do with them? Experience in the 1700s showed that a field army of 100,000 men was simply uncontrollable- bringing that many men to battle, while done a few times, had caused more trouble than the extra men was worth. Even armies of 60,000 to 70,000 men required skilled subordinate commanders throughout the army, good staff work and a massive logistical effort just to get from point A to point B, much less deploy to fight. During the Seven Years War, most battles were fought between armies of 30-50,000 men, which were controllable in battle and easier to feed, especially as the war drug on.

To overcome these problems, the Committee for Public Safety tried a few methods. To solve the problem of getting people to go along with the conscription, and to stay in the army afterwards, the Committee inculcated a sense of nationalism in their new soldiers. They argued that these men would fight to defend France itself- the land, the people, the culture- from attack. They also would fight for the ideals of the new, Revolutionary France. Those ideals granted them more rights, but those rights came with more responsibilities. Defending France was no longer the problem of the King of France, it was the problem of the People of France. These arguments met with the spirit of the times, and brought hundreds of thousands of men into the army.

To deal with the issues of command and control, the French decided that, rather than creating a few large armies that their officers could not control, they created many small armies- between 20,000 and 30,000 men. These armies were small enough for inexperienced officers to control, and large enough to not be completely overwhelmed by an enemy army of 40-50,000 men, if holding a defensive position. They were easier to feed, and could move rather quickly compared to other armies, as well. An overall commander for each area would command both his army, and the armies around him. In theory, these smaller armies would maneuver together under this commander, able to come together or disperse as needed. At least, in theory.

Enter Jean Baptiste Jourdan

Domouriez’s defeat and defection in early 1793 had opened the way for the invasion of northern France. This invasion proceeded along two major lines- a British lead force against Dunkirk, and an Austrian led attack moving down the Sambre towards the main French border forces there. The French deployed several of their smaller armies into the area, under the general command of the Army of the North, which controlled, in total, about 100,00 or so men at any given moment. After Domouriez’s defection, command of the Army of the North fell to the Comte du Custine, who was quickly executed by the Committee for Public Safety for the dual crimes of retreating before the Austrians and being a nobleman. He was replaced by Jean Houchard, who moved to relieve the Siege of Dunkirk

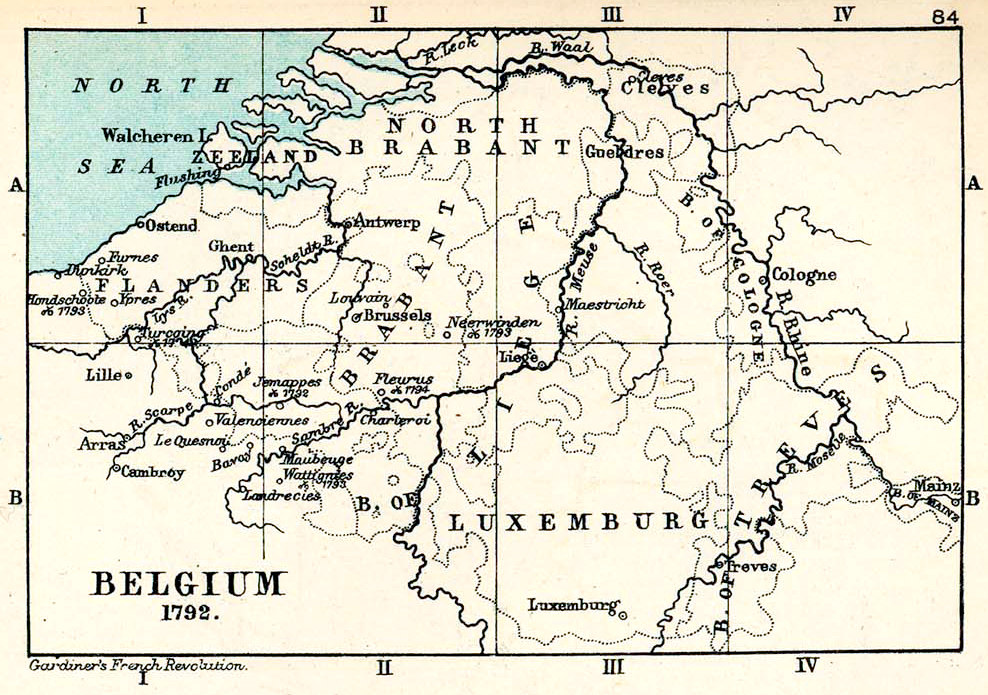

Map of the Flanders Campaign with battles marked.

Houchard was a willing fighter, but had little command experience- in 1792, he was commanding a company of cavalry, and in 1793, he was commanding an army of 100,000 spread out over several miles. In spite of this, he brought his armies together outside of Dunkirk, where he entrusted the main assault against British forces to Jean Baptiste Jourdan, whose previous military experience had been as a private in the Battle of Savannah. Houchard’s assaults eventually dislodge the British forces covering the Siege of Dunkirk, and the British escape. Unable to coordinate his armies after the Battle, known today as Hondschoote, the British got away. Houchard planned to move towards the Sambre to face the attacking Austrians, but the Committee for Public Safety arrested and executed him instead.

The Committee then ordered Jourdan to take control of the entire effort. Given that the last two commanders of the Army of the North had been executed, he was rather reluctant- but, was told that either he did it, or he would be executed in turn. Jourdan accepted command, and the Committee decided to send along Lazare Carnot, the organizer of the Levee en Masse, to supervise his actions. Meanwhile, the Austrians quickly danced around and pushed aside the scattered, smaller French armies along the Sambre to move to the large French fortress of Maubeuge, trapping a French army within its walls at the end of September. The Austrians quickly erected siege works, beginning a heavy bombardment on October 14th. Maubeuge, overstuffed with troops on half-rations, would not last long. However, the large army in the fortress compelled the Austrian commander, the Prince of Couburg, to split his army into two parts: an army of 26,000 men to conduct the siege, and an army of 37,000 to protect the siegeworks from the French. This Army of Observation arrayed itself along the hills to the southwest of Maubeuge.

On his way to Maubeuge, Jourdan began pulling together the disorganized parts of the Army of the North, adding them into his Army of the Moselle. Eventually, he managed to get 45,000 men to the area to the south of Maubeuge. On October 15th, with Maubeuge about to fall, he ordered an attack into the Army of Observation.

The Battle of Wattignies

The Austrians deployed on a wooded ridgeline, with the Sambre on their right, and the village of Beaumont on their left. They had rather extensive fortifications, but had to cover a fairly large front with their forces, which stretched their forces rather thinly. They lacked a strong reserve force, relying on both the siege army and the eventual arrival, they hoped, of the Duke of York, who was rushing from Dunkirk to support the Austrians. This long line meant that, in the end, only about 25,000 Austrians would actually fight in the battle.

Jourdan formed up his men into tight attack columns, just as Dumouriez had for Jemappes. He opened up with a heavy cannonade to soften up the Austrian positions. He concentrated his army against the Austrian flanks at first, with a large force in the Austrian center. The flank attacks began before Jourdan committed his center, as he hoped to shake the Austrian line before making his man effort. An early morning fog gave way around 7:00, and a heavy cannonande began- the French targeting the Austrian fortifications, the Austrians attempting to knock out the French cannons, while the French columns waited outside of artillery range.

On the French left, the attack ended up poorly. Austrian forces on the hilltop deployed a heavy fire, with artillery support. The French gained a little ground, but local Austrian reserves counterattacked, sweeping the French back with some losses. On the French right, French forces found more success. They forced their way into the town of Wattignies, only to be pushed back by a strong Austrian counterattack. However, the early success of both French attacks encouraged Carnot, who went to Jourdan and demanded that he launch the attack in the center, or face arrest. In the center, the Austrians had deployed their best troops in two lines- Croatian skirmishers on the main ridge, with three regiments of grenadiers behind the ridge, safe from French artillery fire. The French columns crested the hill, driving the Croatian skirmishers off the ridge. However, the French faced a point blank fire from the Austrian grenadiers, and their columns faltered. Jourdan himself rode to the head of the columns to make one more attack, but the fire, combined with an Austrian counter attack, drove them off, then back down the hill.

During the night of October 15-16, both sides reshuffled their forces. Couburg brought up some reinforcements from the Siege Army, while Jourdan rallied his men and reorganized them for another attack the next day. Jourdan and Carnot argued about the proper course of action to take. Exactly who said what has been in long dispute, but in the end, Jourdan concentrated his army for one attack on the French right, against Wattignies. Other forces would march out to make supporting attacks against the rest of the Austrian line to hold it in place.

The attack on Wattignies began with the concentrated power of French artillery, in an effort to blast out the Austrians as much as possible. The French formed up into three columns, one led by Jourdan himself, the others led by the only capable French generals on the field, and made an assault on Wattignies. Austrian fire repulsed the first attack. Jourdan rallied for another. It, too, failed. Jourdan called his men together for one last push. This one finally broke into the village itself in the early afternoon.

The Austrians replied to this French success with another counterattack, while Jourdan rushed to pull more men from his reserves into Wattignies. Ultimately, Jourdan won the race to reinforce his breach in the Austrian lines, and repulsed a counterattack. He then began moving to roll up the Austrian line, forcing Couberg to start maneuvering his men to reform his line. However, the Austrians weren’t quite done- as the French started pulling men from the other parts of the line to reinforce the main attack, localized Austrian counterattacks routed several French forces caught in the open. As the day began to fall, the Austrians and French were exhausted by two day’s combat, but the French held the hills that dominated the Austrian siegeworks.

Caught between two armies, Couburg decided to retreat. On October 17th, he packed up the Siege Army and retreated to the north to link up with the Duke of York. Jourdan, fearing a prolonged battle and a trap, decided to stay at Maubeuge, rather than pursue Couburg. In the end of the battle, the Austrians had lost 1000 dead, the French around 1500, with 2000 Austrian wounded and 3000 French wounded. If you’ve been paying attention, you can probably guess what happens next.

Carnot returned to Paris after the battle, where he ordered Jourdan into pursuit of the Austrians. Jourdan left Maubeuge, but the Austrians controlled all the river crossings across the Sambre, which was swelling with the rains of autumn turning into winter. Unable to cross, Jourdan packed it in for the winter, where he was promptly arrested by the Committee. Carnot denounced him to the Committee, and Jourdan refused to mount a defense. However, other members of the Committee, present at the battle, disputed Carnot’s version of the battle. This allowed Jourdan to escape with his life- though, the Committee removed him from command, sending him home.