Well, it’s fair to say we’re getting deep into summer, now. With the heat, today is a good day to relax a bit, and consider some military history.

Spain after Talavera

Talavera proved a great deal about the Peninsular War. It proved that Wellesley could fight against the French and come away victorious. It proved that Spanish troops were not ready to fight in the open against the French, and could only really take the field as guerillas or in fortified positions. It also proved that Wellesley would have to rely on his own supplies and efforts, rather than on the Juntas to provide support for his troops.

The battle also marked some changes. News of the victory led to a new title for Wellesley- Viscount Wellington, awarded to him for his efforts against the French in a time when good news was sorely needed. However, the Austrian defeat at Wagram, and the subsequent Treaty of Schonbrunn, freed up both tens of thousands of troops in central Europe, and the Emperor himself, to deal with Wellington and the Spanish in Spain. Figuring that Napoleon would come down to Spain, and not wanting to have to flee without some sort of precaution, Wellington began a slow movement back to Lisbon, where he began to organize a series of fortifications that would become known as the Lines of Torres Vedras, which we’ll talk about in a bit.

Napoleon sent the troops over the winter of 1809-1810, but he did not come himself. He was in a bit of a domestic pickle- his only son was a bastard, born of his Polish mistress, and claimed by her elderly husband. His marriage to Empress Josephine was effectively over- the numerous affairs the two had had, combined with her fairly low birth for an Empress and the inability of the pair to conceive an heir had left the two basically estranged from each other. As Emperor, Napoleon needed an heir, and, by 1809, he was convinced he would not get one from Josephine. A divorce from her would give him a chance for a new marriage, which would both allow him to produce an heir and solidify his alliance to any of Prussia, Russia and Austria. As was traditional, the Hapsburgs proved most ameniable to marrying off a princess to a French emperor, resulting in a new family for Napoleon. However, the negotiations dragged through the year, and it wasn’t until 1810 that he was finally married. It wasn’t long before Marie Louise was pregnant, though, and Napoleon decided to take 1810 to tend to his wife, and, in early 1811, when she gave birth to a son, he decided to celebrate with another year off from war, leaving the fighting in Spain to his marshals.

While Napoleon did not go to Spain, 100,000 men released from duty in central Europe flooded into Spain, filling the ranks of his armies there. His marshals moved quickly, smashing several Spanish armies over the course of 1809 and 1810, nearly capturing the leaders of the Junta Central in a quick campaign, and recapturing several key cities around. The remaining Bourbon loyalists fled to Cadiz, the last city they held, while Wellington fell back to Portugal. Marshal Victor established a siege of the city of Cadiz, but, as the city was a port, this would prove rather difficult. There would be no way to starve the city- the Royal Navy could bring in all the food the city needed- and so he had to reduce the city by bombardment. However, the city’s location and the local geography made this very difficult, and Victor had to fight off several attempts to relieve the city as well. He was also hampered by a lack of supplies, ammunition, and serious siege artillery. Cadiz would never fall, and, in 1812, after the Battle of Salamanca, Victory would have to abandon the siege. However, most of Spain would, from 1809 to 1812, be ruled by Joseph I Bonaparte, with his French armies battling guerillas to reinforce his rule.

The Lines of Torres Vedras

With Spain increasingly under French control, the time came to, once again, force Portugal to accept French rule. This task fell to the great marshal Massena, who had fought several successful campaigns, both under Napoleon and as an independent commander in Italy during the Revolutionary wars. His experience, Napoleon figured, would carry him well and allow him to defeat Wellington. It took some time for Massena to gather up his troops, and he did not begin his campaign until June of 1810, at the head of 50,000 men. He first marched to Ciudad Rodrigo, the Spanish fortress that guarded the Portuguese border, besieging the city for a month before it fell on July 5th. It took nearly the rest of July to resupply Massena’s army, and he marched on Almedia, the next fortress on the road to Lisbon. Wellington hoped the fortress would last for several weeks, but, a freak shot from the French detonated the powder magazine in the fortress, causing it’s surrender on August 27th.

The sudden loss of Almedia forced Wellington to take the field outside of of Lisbon, in order to delay Massena. However, Massena had his own problems- he had no idea how to find his way anywhere. His maps of the area had been produced in 1778- more than forty years out of date! Roads that existed weren’t on the map, and roads that were on the map were gone. This required Massena to grope his way through the countryside, finding routes as he could while looking for Wellington. The two met on the field at the Battle of Busscaro on Semptember 27th, where Massena failed to dislodge the British. However, he did find a round to outflank the position, which forced Wellington to begin his final retreat into Torres Vedras. As Massena closed on Lisbon, he believed Wellington was in a race to Lisbon to board ships to get out of Portugal, and launched a headlong march to get to him.

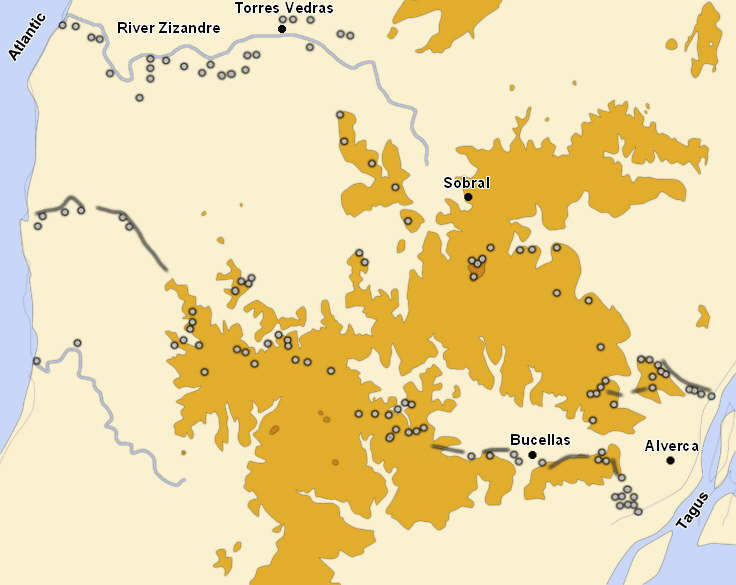

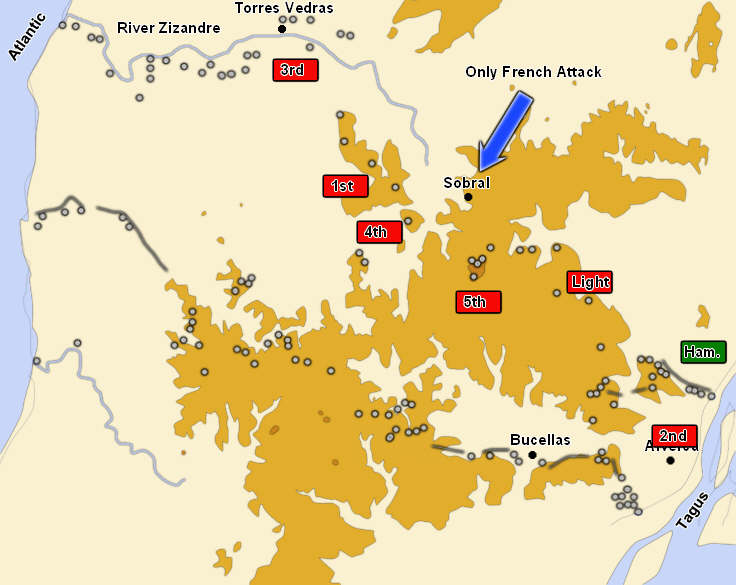

Only in early October did he discover where Wellington was really headed. Each day he had delayed on the campaign, each skirmish, each bit of trouble with supplies, had given the British engineers and the tens of thousands of pressed and conscripted Portuguese laborers more time to complete the fortifications outside Lisbon. In fact, it had allowed the British to turn what was supposed to be a line of picket fortresses into another fully fortified line. The final fortresses consisted of three lines, stretching from the Atlantic to the Tagus River, taking advantage of natural terrain, such as hills, mountains, cliffs and rivers. Two lines lay north of the city, the third covered the loading beaches points- just in case the British had to run for it in the end. Ahead of the lines, and on the retreat, Wellington burned villages and food supplies, evacuated people and other sources of labor to Lisbon, and built up supplies of shot, powder and food in the city with the support of the Royal Navy. He would have plenty of food and supplies, while Massena would have a hard time foraging and would be at the end of his supply tether.

Massena made two attempts to attack the fortifications, on the 10th and 12th of October, 1810. These attacks faltered pretty quickly, and Massena called for reinforcements and more supplies to continue the assaults. In the meantime, he decided to build his own lines and fortifications to wait it all out. After a month, Massena decided to retreat to Santarem, his main supply base, and to wait there. His troops proved excellent foragers, rooting out every possible store of supplies and food in the area. However, in spite of this, thousands of French starved over the course of the winter of 1810-1811, while Massena kept asking for more men, and Wellington kept waiting for him to hurry up and starve already, so that he could force the exhausted French into a fight.

In late February, Massena had no choice but to look for some place that had some food to feed his men. He began a retreat from Torres Vedras, hoping to find food just north of the city. Wellington, however, hounded him first away from Lisbon, then out of Portugal. Massena tried to shift to the south in order to reinvade Portugal, but his men were too exhausted and his supplies too poor to try it, and he fell back further into Spain, still looking for reinforcements and supplies. Once in Spain, however, he was able to start rebuilding his army.

Once Massena was back in Spain, he could shelter his armies behind the fortresses of Almedia and Ciudad Rodrigo, and Wellington would have to take them. While he had plenty of food and men, he did not have a proper siege train. Believing that Massena was effectively unable to act, he settled down to blockade Almedia and force it into starvation on April 10th, 1811. However, Massena was not sitting around feeling sorry for himself- he quickly whipped his army into shape, resupplied and reinforced it back up to nearly 50,000 men, and he marched on Almedia at the end of April, hoping to defeat Wellington and break the siege.

The Battle of Fuentes de Onoro

Massena’s army left Cuidad Rodrigo on May 2nd, under observation from Wellington’s scouts. These scouts and Massena’s light troops skirmished throughout the day, giving Wellington time to maneuver his army to block Massena’s. Wellington has already scouted out an area to deploy his army astride the route from Ciudad Rodrigo and Almedia, which would allow him to both cover the blockade of the fortress and keep the pressure up on the siege. This position was along the Dos Casas River, between Fort Conception, a damaged fortress used by the British as a camp, and the town of Fuentes de Onoro. Along this line, the Dos Casas cut a steep ravine, making it impossible for the French to assault the position directly. That ravine ended around Fuentes de Onoro- further to the south, the river, which is little more than a stream, was quite crossable.

Massena encountered this position on May 3rd, and decided to attack immediately. Seeing little way to come to grips with the British left, he ordered an assault against Fuentes de Onoro itself, launched from a hasty deployment on the afternoon of the 3rd. One corps maneuvered against the British left, to exchange fire across the ravine and pin the British army, while a division made the attack against the town. The first French wave broke into the town itself, while the next forced the British into the isolated, more defensible parts of the town. However, as the day drew to a close, a strong British counterattack drove the French out of the town, leaving about 250 dead on both sides.

May 4th was a fairly slow day, as the two armies faced each other across the Dos Casas, with occasional skirmishes and artillery exchanges. Massena carried out a reconnaissance of the British line, and discovered it ended south of Fuentes de Onoro, with the positions there held by light forces that Massena believed he could push aside. With that discovery, he began planning a massive flank attack for the rest of the day, which would start at first light on the 5th. After turning the British flank, either the British would retreat or reform the army with a refused flank. If Wellington refused the flank, Massena would launch a second attack against Fuentes de Onoro, the hinge of the main line and the refused flank. With the town taken, the French could launch a massive attack against the British right, and destroy Wellington’s army.

Wellington had taken some steps to shore up his position south of Fuentes de Onoro, moving the 7th Division- his weakest- into position to bolster that area. However, dawn on May 5th proved that deployment to be rather insufficient to the task, when a full French corps crossed the Dos Casas, threatening to overwhelm and destroy the 7th Division. Wellington now faced two crises. The first was the French Corps marching to his rear, the other was the extrication of the 7th Division from disaster. The solution to the first was to redeploy several divisions to the flank, which required time. Getting time to redeploy meant sending reinforcements to help the 7th Division immediately.

To gain time and help the 7th, Wellington rushed the elite Light Division out to the flank in front of the French attack. The 7th was able to retreat behind the Lights, who began conducting an excellently managed fighting withdrawal. The infantry skirmished against French skirmishers, while formed units held off more serious attacks. British cavalry drove off the French horse, and then turned to the French artillery, preventing French guns from supporting the attacks. When the French deployed for a serious attack, the British gave way to another position. This skillful work gave Wellington time to deploy three divisions to his flank, hinged at Fuentes de Onoro.

Massena senses that his attack was moving slowly, and so send orders to the Guard Cavalry, deployed nearby, to move to attack the British forces that were slowing his advance. However, the commanders of the Guard units refused to recognize Massena’s authority, insisting their orders come from Bessieres, the Guard commander. However, he was nowhere near the battlefield, off inspecting some minor fortifications no one cared about rather than rushing to the sound of the guns. Without his support, or the support of the Guard, Massena’s flank attack faltered when it arrived against the new British positions.

However, Massena had planned for that, and, around mid morning, launched his second attack, sending another corps against Fuentes de Onoro. The attack went well at first, pushing the British back from the lower points of the town, much as they had on the 3rd. French reinforcements piled into the town over the course of the rest of the morning and into the afternoon, coming in three waves of attacks. However, the final wave drew in troops from the flanks around the town, leaving the French open to a counterattack. The British division closest to the town on the right launched a rapid attack against these weakened forces, even as the French cleared the town. This counterattack threatened to cut the French off in Fuentes de Onoro. Low on ammo, having suffered heavy casualties and exhausted from the fighting, the French forces around the town gave up and began a retreat across the Dos Casas. With the day drawing to a close, Massena decided against renewing the attack. He would wait a few more days near the British army before retreating back to Ciudad Rodrigo. After hearing of Massena’s defeat, Napoleon sacked him.

The battle left behind about 250 dead British and 1200 wounded. The French lost 350 men, and 2100 wounded. Most of the casualties occurred around Fuentes de Onoro.

If you're interested in this topic, feel free to comment below. Also, if you'd like to read more military history here, check out the archive of posts.