Former Alabama, Utah and Michigan cornerback Cam Calhoun commits to Ohio State.

Try as we might, 1809 isn’t done with us yet. This year is one of the most active, if not the most active, in the Napoleonic Era, given the action in Austria and the action in Spain. In fact, it is to Spain we return, to look at what’s happened since the British left, and what happened when they returned.

The Second Invasion of Portugal

The Battle of Corruna left Spain and Portugal without British support. In fact, it wasn’t entirely clear that the British would return- a series of botched expeditions on the Continent had left much of the British government dubious that there could be any serious success against the French on land.

With the British dealt with, the French turned back to the issue of Portugal. The British had tossed them from the country after the Battle of Vimero the previous year, and Napoleon wanted to retake control of the country and its ports, and to force it into the Continental System. (That said, even if Portugal could be forced into the System, it would be hard for anyone to force Brazil to follow along, and that was the part of Portugal the British cared about the most anyway.) The bulk of the invasion would fall to Soult and his 20,000 men, who had chased the British from the Peninsula.

Soult’s men, while well trained and experienced, were short on supplies, and many were sick from the winter campaign. Still, Soult decided to carry out the invasion as quickly as he could. His first stop was the Spanish port of Ferrol, which fell in late January. At Ferrol, he captured several ships, a stockpile of cannon and arms, and food for continuing operations. In March, he crossed into northern Portugal, dispersing a smaller army of Portuguese militia. On the 20th of March, he crushed an army of 25,000 at the Battle of Braga, and another army of similar size a week later at the First Battle of Porto. He stormed the city, capturing it, the arsenal, and the wealth of the city largely intact. With that done, he decided to stay in Porto to rebuild and rest his army, drawing in reinforcements and stragglers- at this point, he was down to about 15,000 men from a nominal strength of 40,000.

Meanwhile, French forces in Spain were largely on the rise, as well. Victor marched south with an army, chasing down Cuesta’s army at the Battle of Medellin at the end of March. Victor smashed the Spanish force, inflicting 8,000 dead for a loss of about 300 men. In Catalonia, St Cyr crushed a force of Spanish guerillas at the Battle of Valles. The only real success came for the Spanish at Vigo, in the north, which would draw a later French reaction. Overall, while the Spanish and Portuguese had little trouble finding men willing to fight, they had little in the way of arms- one Spanish general claimed he had one musket for evert twenty men willing to fight- and those men, while enthusiastic in camp, broke and ran at the sight of French cannon and columns on the attack.

Wellesley Returns to Portugal.

Meanwhile, back in Britain, Arthur Wellesley had to fight for his career. After the Battle of Vimerio, his superiors had stepped in and offer the French overly generous terms at the Convention of Sintra, for which everyone who looked like they had been involved had to come back and face a court of inquiry. Wellesley had made the initial armistice after the Battle, but objected to the Convention and refused to sign it. This ended up saving his position, and his superiors decided to retire from the army rather than continue with any proceedings. The Government was happy to be done with the whole thing.

While Wellesley was still in uniform and holding general rank, he didn’t have a command, nor was one in the offing- the Government wasn’t overly interested in another expedition, and India was largely peaceful. So, Wellesley decided to drum something up. He wrote to the Prime Minister, arguing that Portugal would make a good base for anti-French operations. The Portuguese fought well with British support, Lisbon would make a great base that could be supported by the Royal Navy, and the mountains and hills on Portugal’s borders would make a strong defensive refuge from which to fight the French in Spain and Portugal. There were already British advisors in Lisbon, training and preparing a new army anyway. Lord Castlereagh decided to make one last try against the French, and gave Wellesley an army and supreme command in the area. He arrived in Lisbon in April, 1809.

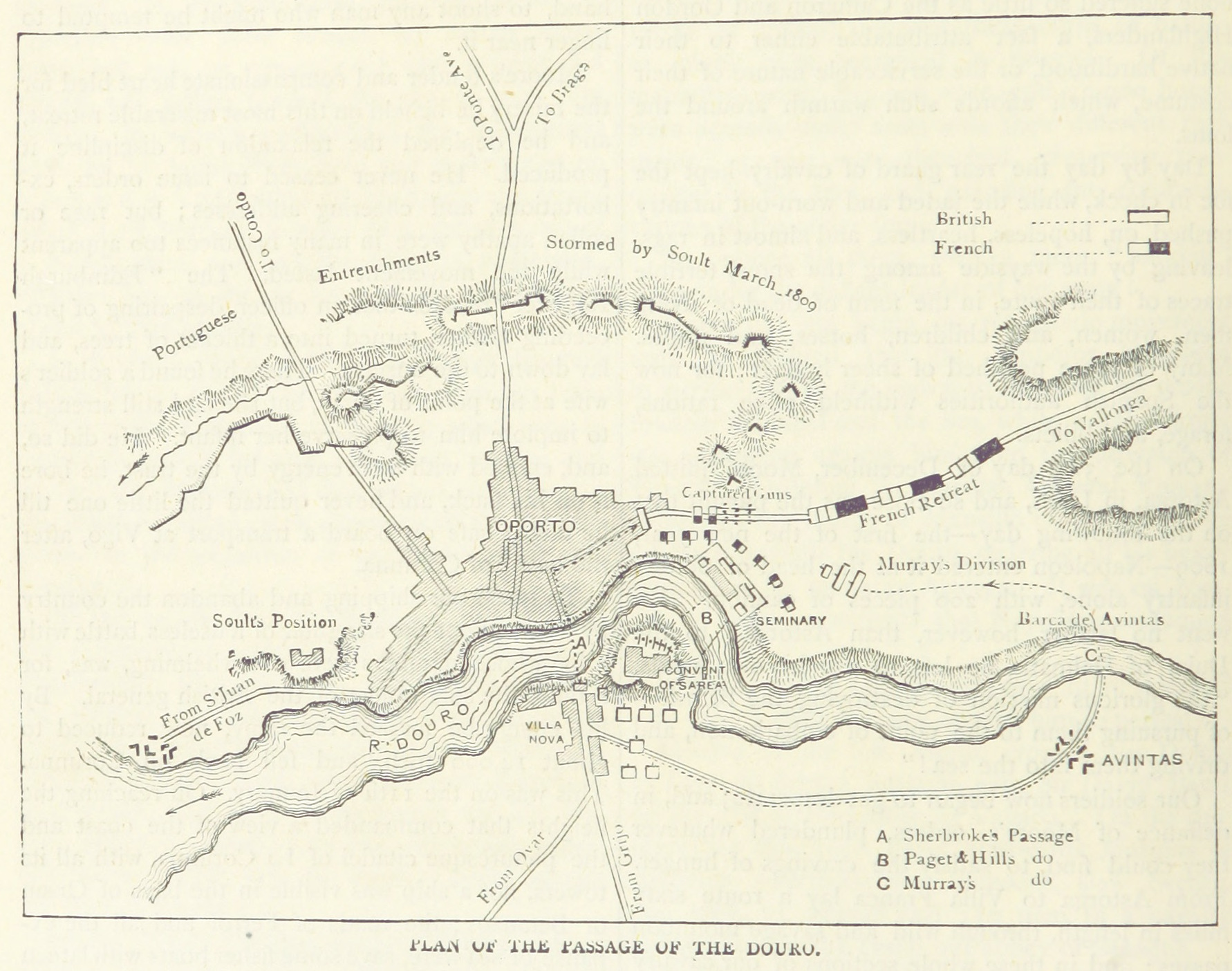

He spent April getting his army organized, integrating the professionally trained Portuguese troops into his command. In May, he marched north against Soult. Soult had his own troubles- guerillas had cut off his main supply route, and he had detached a large force to deal with it just before Wellesley arrived. Soult retreated across the Duroro River into the city, holding the British off with a skirmish to the south. However, with the help of an enterprising Portuguese barber, the British stole a few boats and made several crossings. Soult tried to break the landing areas, but failed to push the British back. Rather than duke it out against a larger army, Soult abandoned the city, retreating to northern Spain. Wellesley’s pursuit cost the French thousands of men and 50 cannon, by the end of it.

With Soult out of the way, Wellesley decided to try and link up with the Spanish forces fighting Victor, and support a growing Spanish offensive against Madrid, Josephs’ seat of authority in Spain. This would prove more difficult. In order to do so, he had to coordinate with two Spanish armies, one under Cuesta, who viewed Wellesley as a rival for Supreme Commander of the Spanish Armies under the Junta Central, and another under Vengas, who had his own French army nearby to deal with, and also was not the most reliable of campaigners- his sense of timing was poor, and his natural caution often meant inaction in the face of opportunity. Wellesley also faced chronic supply problems. He believed that Central Spain had to be at least as prosperous as Portugal- it wasn’t- and he believed the Spanish when they said they had enough supplies to feed his army- they didn’t. Later campaigns would see Wellesley acting differently towards the Spanish, and with greater support from Britain itself.

Victor’s situation in Estramurda wasn’t exactly peachy, either. The poor supply in the area made it imperative that he keep his supply line back to Madrid open, but guerilla attacks made that difficult. Once he heard Wellesley and Cuesta were on the move, Victor began a series of retreats up his supply line up towards Madrid. Wellesley tried to chase him, but ran into a series of difficulties trying to coordinate his movements with the Spanish in order to bring them together near Madrid against either Victor or Sebastini. However, after moving throughout June and most of July, he had managed only to link up with Cuesta and march on Victor’s Corps, which held the town of Talavera. While not the idea outcome he had hoped for, by July 20th, he had 50,000 men against Victor’s On July 22nd, he found Victor’s troops ready for a fight along the Alberche River. He convinced Cuesta to support him on the 23rd, but while the British were ready to go, the Spanish never made it to the battlefield. By the 24th, Victor was back on the road to Toledo. Now, it was Cuesta’s turn to demand action, and Wellesley’s to refuse, on account of poor supplies. Cuesta fell on Victor’s heels, marching on Toledo, believing he was chasing a smaller, demoralized army.

Cuesta found an army of nearly 50,000 ready to go troops in Toledo. Sebastini had slipped Venegas in the previous days, linked up with Joseph’s reserve force, and then joined Victor in Toledo. Cuesta refused to fight this army, retreating quickly back towards Talavera and Wellesley, with the French in pursuit. By July 26th, Cuesta had recrossed the Alberche River and rejoined the British. Wellsley had spent the previous days reconnoitering the area, and selected a defensive position outside the city, between the town and a large hill, the Cerro of Medellin.

The Battle of Talavera

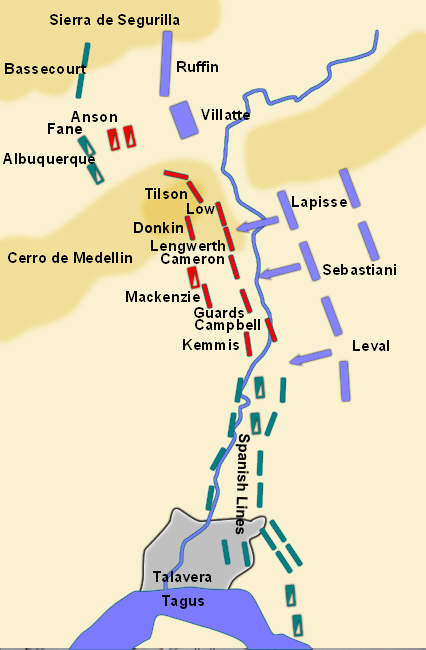

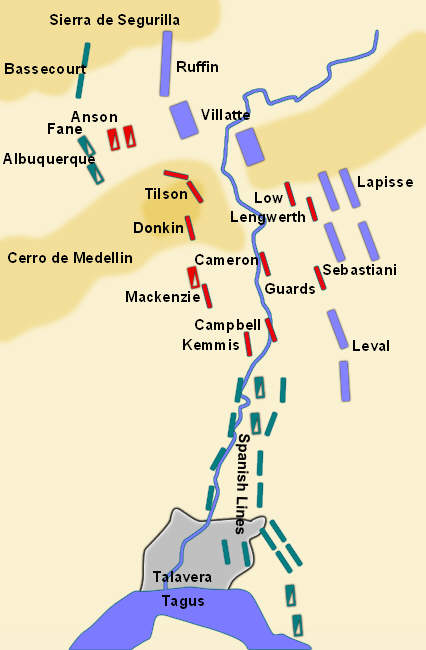

Wellesley managed to impress on Cuesta the importance of fighting the French defensively. The area around Talavera was quite defensible, and, Wellesley believed, suitable for the poorly trained and skittish Spanish. It offered a large number of walled estates that supported olive farms. The large plants and berms to support them also offered a number of covered positions that, with a day’s work, made the area nearly impenetrable. With his flank on the Tagus River, Cuesta could stand secure in his spot, and, later, would prove reluctant to leave it once set in. The British deployed to the north of Cuesta, anchoring their flank on the Cerro of Medellin. They deployed in a strong double line, with their front to a stream that fed into the Tagus to the south. Between the two armies, the Allies had about 53,000 men and 60 guns.

The French army, while numerically inferior, was, overall, of better quality. Most of the troops were French veterans, far superior to the large Spanish force and better than most of the British troops. They were outnumbered by about 10,000 men, but had a 20 gun advantage in artillery. However, they suffered from a highly confused command structure. King Joseph was in nominal command, however, he had no experience in combat. Instead, his military advisor, Jean Baptiste Jourdan, the Revoutionary hero, took overall command. However, Jourdan did not get along well with Victor, who had an impetious temperament that chafed in subordination after so long in charge of an effectively independent command. Victor would take many actions on his own in the battle. Another wildcard, which weighed heavily on the mind of Jourdan, was Soult. Soult’s corps, recovered from its retreat fron Portugal, was on the march and heading to cut off the Allied army from the rear. As a result, Jourdan was willing to wait for action, even if his chief subordinate, Victor, wasn’t.

After skirmishing on the afternoon of July 27th, the British and Spanish drew up in their positions. A French cavalry force went to take a look at the field. A Spanish unit, despite the impossibly long range, fired a volley at the French, which promptly caused the division next to them to break the field and run, leaving a gap in the Spanish lines that the French ignored. To the north, Victor set up an artillery park to bombard the British position. Jourdan was largely willing to wait until the next day for battle, but Victor wasn’t. During the night of July 27th/28th, he launched an attack against the Cerro, attempting to gain the heights overlooking the allied position. A poor British deployment allowed a French force to gain the summit temporarily, but a strong counterattack pushed them out before dawn.

As dawn broke on the 28th, Jourdan was largely content to hold back and wait for Soult to arrive. However, Victor decided to make another attack at dawn, hoping to gain the Cerro. The British held the reverse slope of the hill, which sheltered them from Victor’s bombardment. Using the same force that had made the night attack, Victor’s men advanced in column against the British force, which waited until the French entered close range before mounting the summit to pour fire down the slope. The units on the flank of the French column moved for a counter attack, driving the French back off the hill.

With that attack repulsed, a lull fell in the battle as Jourdan ordered Victor to report for a council of war. While Jourdan planned to wait for Soult’s troops to arrive, over the course of the morning, two bits of news came to the French. The first was that Soult’s arrival was going to be later than expected, owing to the poor roads he had to deal with. The other was that Vegaras had gotten off his duff, and began marching on Toledo. Between these two events, Jourdan could no longer afford to wait for Soult, and needed to deal with the army in front of him now so that he could move to defend Toledo. To that end, he decided to organize a major attack that afternoon. The main attack, against the British center, would be assigned to Sebastini’s troops, while Victor was given the task of marching to the north, around the Cerro, and flanking the British to the north.

The attacks were supposed to go off at the same time, around 1500, but that didn’t work out. One attack, led by General Leval, was to hit the junction between the British and Spanish armies, to keep Cuesta from coming out and supporting the British. However, Leval’s men got lost in the olive groves and farms, and, believing that his maneuver had taken much longer than it really had, Leval launched his attack at 1430. Despite this, he made some progress until the Spanish artillery in the area cracked his central column. Seeing them in disarray, the British troops to the north counterattacked, driving the French back just as the other units began to move forward.

The fight in the center started well for the British. Using the local terrain to mitigate Sebastini’s bombardment, the British troops held their volleys until the French were within 50 yards of their lines, then fired at once. A shattering fire stuttered, slowed, then stopped the French attack. Seeing the French wavering, the British launched a sharp counterattack, driving the French back. However, the local British commander, Sherbrooke, lost control of the attack, and it ran right into the French reserves.

This time, it was the French’s turn to deliver a shattering close range volley and counterattack. The French reserve surged forward, and the British began a headlong retreat. It also provoked a moment of crisis for Wellesley. He at troops in the north to stop that part of the French attack, but the attack had left a massive gap between his army and the Spanish army. Meanwhile, Victor continued his advance on the British flank. In spite of this threat, Wellesley pulled men off the Cerro into the gap. The reinforcments held long enough to allow the retreating British to reform behind them, then move to stop the French attack. Rather than risk a headlong attack again, Sebastini opted for a musketry duel with the British before forming up for another attack. The British quickly gained fire superiority over the French, and, about 1700 or so, the French center began to pack it in for the day, falling apart and falling back.

Victor’s flanking attack never really developed. Wellesley deployed the Portuguese to stand Victor off, while bombarding him from the Cerro. This slowed the advance in this area, which the British tried to delay further with a cavalry charge- that ran right into a ravine that no one knew about until the horses ran into it. The French trapped and inflicted heavy losses on this attack. However, once it was over, word came that the French center had collapsed, and this force fell back too for the day. Defeated, Jourdan left in the evening to return to Toledo and save Madrid from attack. He left behind 800 dead and 700 prisoners, with 6300 wounded. The British suffered the same amount of dead, roughly, but only 3200 wounded in the end. However, despite his victory, Wellesley had to stop to recover. By the time he was ready to move to Madrid, he discovered Soult had finally arrived- with 50,000 men astride the British line of supply. In early August, the Allies retreated to the south, while Jourdan defeated the Spanish army outside of Madrid. In the end, Wellesley ended up back in Portugal, preparing for further fighting around Lisbon.

If you found this post interesting, feel free to comment below. If you're a little behind and want to catch up, check out the archive here.