You're not going to believe the new kid Reecie. He looks like he's already a senior.

The buzz was about a rising eighth grader set to enroll at Austintown-Fitch High School located outside of Youngstown in the summer of 1998. As is often the case with grassroots guerrilla publicity, people who had never laid eyes on him were already gushing over how talented he was.

Superlatives were registered, deployed, overshared and ultimately exhausted throughout town. As the school year approached and football season began, man amongst boys steadily rose to the top. And there were whispers about if that could literally be the case.

Three full years before Danny Almonte's age would be questioned following the Little League World Series, many people around Northeast Ohio were not convinced that Maurice Clarett could really be just an incoming high school freshman.

"I remember thinking that he was just going to be some taller, faster guy," said Nate Ortiz, who was also an incoming Fitch freshman in 1998. "Then I saw him and thought there was no way he was in my grade. Way too big. Way too fast. Way too strong. And he did way too many amazing things."

It was evident to those who saw him – or those who had never seen him but still graciously spent the summer spreading his hype – that his physical talent was elite; matched only by his drive, which made him terrifying to defend.

The man amongst boys chatter had checked out once two-a-days began in earnest, and as everyone quickly discovered, Clarett was a true freshman. He was just a boy. But not everyone knew why or how he ended up there.

Clarett was at Fitch because he was getting a second chance. It was the first in a series of second chances.

He should have been in jail his freshman year, serving time for breaking and entering in a burglary attempt that had gone awry. One of the officers working at the detention center where Clarett was locked up was a man named Roland Smith, who convinced the judge that this talented kid (whose skill obviously wasn't in successful burglaries) just needed a change of scenery.

And that's all Fitch was. New surroundings, a new focus and a get-out-of-jail-for-football card.

"Everyone was taken aback by how good he was," said Ortiz of Clarett, who subbed in for varsity games as a freshman and played with the team all season, attracting new fans to the stadium. "He returned kicks, he did amazing things – he was the real deal."

You're not going to believe the new kid Reecie. He plays like he's already in college.

It was more of the same when basketball season started. Clarett made the JV and dressed for varsity games, but not even halfway into the first year of that second chance he decided to transfer to Warren Harding High, 20 miles north on the map but a thousand miles away where elevating his football stature was concerned.

“The feeling (when Clarett transferred to Harding) was that he was such a huge talent that he was just trying to make the best move for himself," said Ortiz. "No one had any ill feelings toward him for leaving. He was always so nice and respectful to everyone. There was nothing arrogant about him."

They were classmates for only about a semester of high school before Clarett departed. Separate directions, multiple lifetimes and 12 years later their paths would cross again.

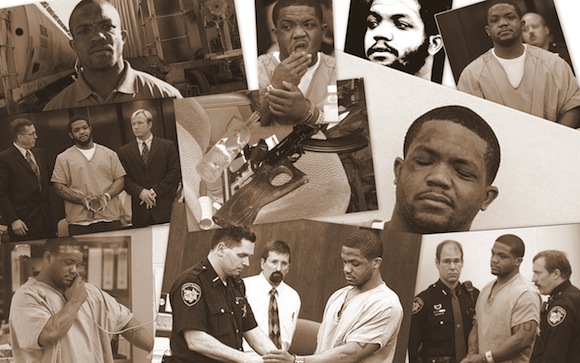

Clarett found himself in quite a bit of trouble before he arrived at Ohio State, but he got bailed out and landed at Fitch. The trouble continued during his single, resplendent season at Ohio State, but there was no soft landing that time, and his actions cost him his eligibility.

When trouble happened again in the years following his celebrated college career, he landed in federal prison for almost four years. The last time I spoke with Clarett specifically about his time in prison, he had just resumed his professional football career.

We've stayed in touch since then, but not to talk about his past – and definitely not to talk about being behind bars. Mostly we have talked about Ohio State football – that's what you would want to talk about with Maurice Clarett, right? Well, he really likes to talk about the Buckeyes too.

The first text I received after Kenny Guiton led the team to an improbable come-from-behind win against Purdue last October happened to be from Ohio State's most notorious occupant of Guiton's jersey.

Clarett: I had more fun watching #13 than you could imagine. I'm so happy for him.

Me: The last time I saw the stadium cheering a #13 that loudly it was because some freshman was running away from Michigan linebackers.

As was the case with Hurricane Irene, the first message I received after my New Jersey neighborhood was walloped by Hurricane Sandy was from Clarett checking to see if if everyone was okay and if I still had a house (they were, and I did). The first text I sent the morning of the Ohio State-Michigan game this past November was to him.

Me: Are you going to be on the field today with the rest of the 2002 team?

Clarett: Yeah. Really looking forward to it.

Me: Good. Ohio State should win then. You're basically loss-repellant.

Clarett: LOL. Yes.

The Buckeyes beat the Wolverines with Clarett on the sideline and finished their perfect season with him there in attendance, just as they had when he had worn Guiton's current jersey ten years earlier.

When we met up in Columbus prior to the Nebraska game for dinner last October, I gleefully announced that I would be ordering a rack of ribs. Clarett, whose t-shirt was stretched tightly around his arms and chest but hung loosely on his midsection deadpanned, "Cool. I don't eat pork."

He proceeded to pick apart and consume an entire roasted chicken instead. He might have accidentally consumed a few bones too.

So there were dozens of conversations and a memorable meal in between our last story and the one you're reading, but they might as well have occurred on the same tape. When we began working together on this story he wasted no time in picking up where we concluded two Augusts ago.

"I just never understood my own circumstances," said Clarett, matter-of-factly, of his recklessness prior to life in Toledo Correctional. "I constantly made bad choices. That's what led to my downfall."

A chorus of easy excuses for Clarett immediately filled my head, shaped by comfortable assumptions. But you had a rough upbringing, grew up in a tough neighborhood, were thrust into different surroundings multiple times, went from a predominantly black school to predominantly white school to Harding to the Ohio State to Los Angeles to Toledo to Omaha to –

"Making bad choices landed me in prison," Clarett emphasized. "I led to my downfall."

He isn't willing to blame circumstance or environment for any of his troubles. Initially the conclusion might be that his position is part of an elaborate contrition play to curry favor with spurned Ohio State stakeholders, Clarett stakeholders and whoever might find a thrill in his penitence. It's a lazy conclusion.

He's both smarter and more complex than such an assumption would suggest. While he hesitates to blame the circumstances around his formative years for his missteps, he still wants to change those circumstances – just not for him. It's way too late to change them for his younger self.

Clarett owns all of his misgivings in part because he owns all of his triumphs as well. All of the credit; all of the blame. He quickly deflected my interrogation.

"What decisions would you tell young people to make where you grew up?" he asked me.

"Making bad choices landed me in prison," Clarett emphasized. I led to my downfall."

I was raised in Upper Arlington in the 1980s; the quaint, affluent and figurative island just over the west bank of the Olentangy River by Ohio State's main campus. My mind raced with sarcastic responses: Um, don't wear Gucci on Thursdays. Perrier has an optimal serving temperature. Remember, Michigan is a safety school.

He gave me no opportunity to answer. "It doesn't matter," he said. "Those kids don't have it easy. They have temptations and bad influences too. Maybe they were different, but they have them. You have them."

Sure, temptation is everywhere. The Original Sin didn't go down in Youngstown; snakes come in all shapes and sizes. The crime that landed Clarett at Fitch instead of juvenile detention culminated with him diving head-first out of the second story window of a house he was robbing. The man of the house wasn't supposed to be home at the time. He was.

After making it to Ohio State and landing the starting job, Clarett wanted to be the big man on campus and the center of attention – but it didn't matter what kind of attention it was. The seeds of temptation were planted in him early on, and he cultivated them all the way into incarceration.

"You have no idea how appealing street life looks when you're a kid where I grew up," said Clarett. "Decision-making? Education? The pitfalls of street life? I blocked that out. I didn't want to hear it or know about what could happen. Coach Tressel tried to get me to see that."

"Did it work?" I asked.

"I told him, 'Tress, all the stuff you tried to teach me I'm learning now. Thank you so much.' And he said he was proud of me."

"When did you tell him that?" I asked. Clarett hesitated before answering.

"After prison."

Tressel knew Clarett in his youth, kept in touch with him once he moved to California following his time at Ohio State and even mailed him a book when he was locked up in Toledo. They always stayed connected, just as they will always be connected in Buckeye football lore. These days they talk to each other all the time.

The freshman who had no filter doesn't use hindsight as a crutch or a vehicle for regret. He is far more keen on diagnosing why things happened and is determined to exploit that hindsight to help others like him gain self-awareness – but far earlier than he did.

"As a star athlete (at Harding) my ego was way too big to keep me fearing consequences," Clarett said. "Young dudes ran the neighborhood – it's the same in inner cities everywhere. Coaches get athletes like me who come from where I came from and then suddenly we're in front of cameras and microphones."

The 2002 season wasn't even one-third complete when Clarett was commenting about seeing #13 jerseys in storefronts and on the backs of paying customers, arguing with coaches during games, butting heads with Andy Geiger – all in the public eye. He was used to being charge. He was one of those young guys who ran the neighborhood and he wasn't used to answering to others.

He was more accustomed to being answered to. Clarett was both reflecting on himself and countless other young dudes like him who ran their neighborhoods.

"I hope they get it," he said. "Everyone from Braxton Miller to Carlos Hyde to Christian Bryant - we are all the same."

"Athletes like that are mature athletically but they really don’t know anything socially," he said. "They don’t understand. But don't feel sorry for those guys; just equip them to be better. Maybe they don't have a mother, or they don't know their father – we need to put them in position to better understand their circumstances. It's more than just saying kid, do this or hey, don't do that. Kids do or say something stupid and end up in trouble and then they get mad at themselves. But they still aren't quite sure what they did wrong."

You're not going to believe the grown-up Reecie. He sounds like he's really turned a corner.

Cautionary tales have a way of remaining both static and convenient. They're generally told on behalf of a protagonist who is wasting away in prison for a crime, or in a permanent vegetative state from a car accident that occurred because she was texting while driving, or deceased by their own, accidental or foolish hand. The lessons are easy to learn from the fallen who cannot speak for themselves.

Clarett realizes that he is a cautionary tale. More importantly, he has seized on the opportunity to be the vehicle for his own story so that others like him can learn from the source.

He was there the entire time. Every single Clarett story you've heard – true or otherwise – features him in a starring role.

So he chooses to deliver his own cautionary tale, both to help younger people but also to be a steward of his own history. He frames his past through a remorseful lens for others to consume, digest and gain personal nourishment. What he put himself through and what he endured – as well as what he learned – are all teachable moments. They happened for a reason, and he's vocal about being better now because of surviving what happened.

If you're thinking hmm, teachable moments...that sounds an awful lot like something Tressel would say then congratulations – you're correct. Clarett is finally fluent in his former coach's lessons.

"When you live your life on the streets, you either end up in prison or dead," said Clarett. "Make better people and they'll live better lives. They will actually have lives. Kids like me put so much energy into getting an NFL contract and they think that’s all that matters. But that’s before they become acquainted with vultures."

"Are you worried about current Buckeyes?" I asked.

"I hope they get it," he said. "Everyone from Braxton Miller to Carlos Hyde to Christian Bryant – we are all the same. Help them, advise them, guide them. It's the cautionary tale that makes you reconsider your moves. Whenever you see someone screw up in the movies or on TV, a lot of those times the guys who make those mistakes are old or too unrealistic. It's hard to learn from people you can't relate to."

He didn't directly answer the question about trouble finding current Buckeyes, but it seemed that he hoped his cautionary tale would find them first. "So, you're saying those guys can relate to you?" I asked.

"The 30 for 30 documentary that we're shooting is that movie where someone screws up and pays the price for it. But that guy who makes those mistakes is me." Clarett said. "I'm real, and I'm 29. When you live your life on the streets," he repeated, "you either end up in prison or dead. I ended up in prison."

"And then you ended up in Omaha." I said.

"I ended up in Omaha," said Clarett. "I went from sitting in a jail cell for four years to sitting across from Warren Buffett for three hours in the span of a couple months."

Once Clarett left prison he was able to avoid staying in a halfway house on account of joining the Omaha Nighthawks of the UFL. Those 2011 Nighthawks were coached by their then-new president Joe Moglia, the chairman and former CEO of TD Ameritrade.

One day Moglia and his Ohio State signee, still a newly free man, went golfing. As is the case with most rounds, the afternoon was more about the conversation than the drives and putts.

Four years in the clink provided Clarett with ample time to read, and he took full advantage of it. Ironically, he re-entered the world knowing exponentially more about it than he did when he was punitively isolated from it.

"I came out of jail and I felt so much more informed," he said. "It's cool to be able to handle your business. It's cool to lead. It's cool to be uplifting." Clarett then paused for several seconds. "It's cool to do what Coach Tressel was trying to do with me."

As Clarett played golf with Moglia, he shared his appetite for reading and learning more. The ink on his contract with the Nighthawks was barely dry, yet he was far more interested talking to his boss about life after football than football itself.

He asked his coach – who had built what became the largest online discount brokerage in the world – about business and investing. Moglia told him how many of the CEOs who proudly appear in lists published by Forbes and Fortune inherited their wealth. They were born with head starts. He said that Clarett had less to learn from people like that than he could from someone who built an empire by himself.

So Moglia gave Clarett a phone number. Clarett called it and left a message, and moments later Berkshire Hathaway CEO Warren Buffett called him back and invited him to his office.

"Companies spend a fortune just to meet with Mr. Buffett," said Clarett. "He invited me to hang out and we spent three hours together. It was the coolest experience, joking back and forth with a guy who could buy the entire NFL and the NBA and still have money left over." (Ed. That would cost less than $62B, which is less than Buffett's net worth)

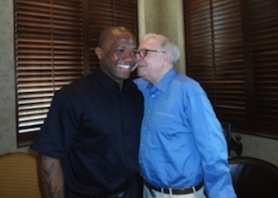

Clarett and Buffett in 2011.

Clarett and Buffett in 2011.

"We talked about emerging from the financial crisis and how he operates on a daily basis," said Clarett. "He doesn't take more than seven phone calls a day to avoid distractions. Focusing and accomplishing goals is largely about keeping distractions to a minimum. Mr. Buffett reads for four hours every day. He knows more about businesses than the owners of those businesses do."

Buffett's wealth did not impress him nearly as much as his methods, his discipline and his community impact.

“He takes care of that town and that town is a reflection of him," said Clarett. "My inspiration today comes from Omaha. I've never seen a more supportive community in my entire life. People there help each other; it's in their culture. When I went to enroll my daughter in school there, the other children there were being escorted by their parents – along with their uncles, aunts, grandparents, whomever – everyone in those kids' lives was there to send them off."

"Ah," I said. "So the question then is how to get Youngstown to become a little more like Omaha – but without the assistance of a local multi-billionaire philanthropist."

"Yeah," Clarett said. "This is how you can help more kids there succeed. Kids that don’t have that kind of support system."

"So how do you do it?" I asked. He answered without hesitation.

"You quit talking about doing it. And you just go do it."

You might not remember me, but we went to high school together at Fitch. I want you to share your story about how you changed your life.

Ortiz sent a Facebook message to a profile belonging to a "Maurice Clarett." He didn't know if it was the real Reece, the kid who had played one memorable football season and half of a basketball season at his school back in 1998. Ortiz was working with The Riot, which is a youth center associated with the Victory Christian Church in town.

The Riot has a program called Reach One, where kids are exposed to life-changing stories from which they can gain encouragement. They hear of triumphs and failures, successes and – as it would turn out – famous local cautionary tales.

The "Maurice Clarett" that Ortiz messaged was, in fact, Clarett, who promised to come visit The Riot.

"It's like a mini-Woody Hayes Athletic Complex," Clarett said, laughing. "I was struck by how pure it was and amazed at how much they offered these kids."

The Riot is open and not exclusive to church members. Ortiz says they draw from Youngstown as well as several towns including several kids from Pennsylvania, who come to play basketball, volleyball, attend concerts, use the WiFi in the cafe, hang out and gain a greater sense of purpose.

"We try to relate to these kids," said Ortiz. "They're from rougher neighborhoods, single-parent households – our leaders can offer options to those kids who think that life gave them a raw deal. Additionally, there are challenges for kids from better neighborhoods with healthier home lives too. This is an inclusive organization."

Clarett arrived at The Riot weeks later and sat on a stool with Ortiz before dozens of kids who had assembled. He told them about how he had changed his life – just as Ortiz had requested – and answered every question, ranging from details of his time at Ohio State to his pitfalls, the false appeal of street life and how he defined personal success.

"When you live the street life, you end up in prison or dead," Clarett told them. "When you live a privileged existence, your life passes unchallenged. There's no fulfillment there either way. You've got to do more. You owe it to yourself and to those who come after you."

The session might have had as large of an impact on Clarett as it had on his audience.

“Let's get these inner-city kids thinking positively," said Clarett, whose tone noticeably gains passion when speaking of The Riot. "Let's get them into math and science. Let's give them introspection and spirituality."

As he was speaking to the kids at The Riot, reporters were assembling nearby to pepper him with questions, but not about him: It was early 2011, and the layers of Tatgate were being freshly peeled back. They were there to ask him about Tressel.

Clarett finished his visit to The Riot, then went back to Omaha. He answered some of those questions about his mentor, but by and large he avoided the spectacle. The sadness he had over Tressel's troubles was tempered by his enthusiasm for the work with kids he was now finding himself doing more often.

"(Ortiz and I) stayed in touch from that point on," Clarett said. "I worked with (The Riot) a few more times, and each time I thought 'man, this dude is serious.' I think I can do even more with some of the guys from here who have gone on to make something of themselves. We all need to give back."

“Let's get these inner city kids thinking positively. Let's get them into math and science. Let's give the introspection and spirituality."

That even more, as it turns out, grew into The Comeback Project. It's a basketball game that's being held April 27 to benefit The Riot, whose team that afternoon will be coached by WKBN news anchor Dave Sess and represented by kids who attend the youth center.

They will face a team of pros, featuring Clarett, Boom Herron, Mario Manningham, Prescott Burgess and other NFL players from the region. That team will be coached by Tressel. (Ed. You can purchase $10, $15 or $20 tickets here)

ESPN Films will be in attendance to film another segment that will be included in the upcoming 30 for 30 documentary on Clarett. It's a project in which he is a very active participant.

"It's really hard to walk around being constantly misunderstood," Clarett said. "I realize that I bear much of that responsibility. Still, it's a relief to put my story in the hands of guys (directors Michael and Jeff Zimbalist, whose first 30 for 30 film was The Two Escobars) who get the culture, understand how and why things happened and can accurately and effectively portray what went on during different moments of my life."

It would be impossible to tell Clarett's story without having Tressel in a prominent, supporting role. Clarett, who rejected his coach's pleas for him to see the big picture when he was still a teenager, now fiercely defends one of his closest friends.

"Coach Tressel is a big part of my life," Clarett said. "He's in (the film) too. My life before and beyond Ohio State are covered. When I asked Tress to get involved he did so without hesitation. When I asked him to help me with The Riot, he said, 'Reece, whenever you want to do something positive for our community, I'm there. I'll always help you.'"

That segment of the documentary should effectively capture Clarett on the brighter side of his transformation from the troubled but immensely talented football player that made – and to a large degree – still keeps him famous as he prepares to turn 30.

"People hear rumors or read stories and think they know you," Clarett said with a smile. "I have my own identity, but I would have benefited from something like (The Riot). This is a springboard. If a person wants to become an engineer or a poet they can learn how to pursue that here. I only knew how to pursue football. Now I'm pursuing something bigger."

You're not going to believe the new kid Reecie. He thinks he can change the world.