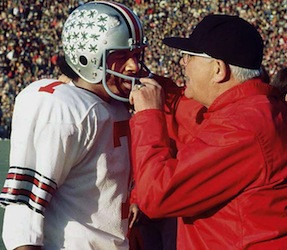

Woody advising Cornelius that milk can make ulcers worse

Woody advising Cornelius that milk can make ulcers worseEd: Special thanks to Cornelius Green, who took the time to sit down with me and talk about his football career and time at Ohio State, where he played from 1972-75. This is the first part of his story.

Forty years ago, Cornelius Green1 was a freshman quarterback at Ohio State. Far from home, the Washington, D.C. native was having trouble sleeping, due in part to recurring stomach pains. One day, his coach, the legendary Woody Hayes, sent him to the doctor to find out what was wrong.

"You're number five," the doctor told the confused 18-year-old. Green tried to correct him, informing him that he wore the #7 jersey instead.

"No," the doctor clarified. "You're the fifth quarterback that Woody has given an ulcer."

He was at once just like other Buckeye QBs before him and also completely unique. In 1972, 82 years after it was first established, the Ohio State football program had its first African-American quarterback in the young man nicknamed "Corny."

Although he barely saw the field his freshman season, he received hate mail from the KKK and the occasional threatening phone call to his dorm room, which he shared with teammate Archie Griffin2, the eventual two-time Heisman Trophy winner. It was a trying time, but Corny believed in the motto "what is to be is up to me." When the media asked him numerous times that year what it felt like being the first black quarterback at Ohio State, his reaction was, "it's like being a quarterback."

It was the same philosophy shared by his coach, who told his players, "if you're good enough, you'll play and if you're not, you won't."

At his first summer camp as a Buckeye, Green roomed with wingback Brian Baschnagel, a white freshman from the suburbs of Pittsburgh. Despite their initial weariness due to their vastly different upbringings, they got along swimmingly. Whatever racially based warnings Cornelius had to deal with from the outside did not extend to his team.

On August 28th, 1963, when Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his famous "I Have a Dream Speech", a young Corny was in attendance. Out of curiosity, he followed a throng of D.C. visitors to the National Mall and witnessed history. Less than a decade later, it only seemed appropriate that he would make some of his own, on a team whose players didn't judge each other by the color of their skin.

Cornelius claims "that day changed my life", and after the momentous event, he went on participate in football, basketball, and baseball, eventually earning nine varsity letters at Dunbar High School.

As a high school player, Cornelius liked to stand out, in part so his mother could easily spot him from her seat in the stands. His father never got that chance. By the time Corny was in eighth grade, diabetes had taken his father's sight and both his legs. Even now, it makes him tear up knowing his father was unable to attend his games and watch his success on the field.

Nevertheless, Cornelius wanted to be noticed, and his penchant for wearing colorful shoes and tassels on his pants caused Washington Post writer Leonard Shapiro to describe him as a "flamboyant flim-flam man." Taking that characterization and running with it, the teenager taped "Flamboyant" on his helmet until one day his nickname simply became "Flam."

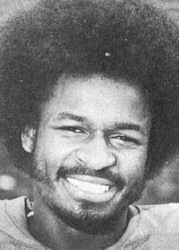

Cornelius was easy to pick out in a crowd

Cornelius was easy to pick out in a crowdDuring his senior year in high school, the All-American threw for 28 touchdowns and ran for 12. His ability to pass the ball and his flashy persona seemed at odds with the buttoned-down nature of Woody Hayes, both as a person and as a coach with a "three yards and a cloud of dust" offense. But as the scholarship offers in football and basketball came pouring in, one of them was from Ohio State.

Also on the table was a contract with the St. Louis Cardinals worth $300,000. However, Corny was raised by a woman who only made it through the eighth grade and valued education above all else.

In the end, his decision came down between Ohio State and Michigan State. From ages 9 to 15, he had spent his summers in Flint, Michigan, where his mother's three brothers lived. It felt like fate to go to college in nearby East Lansing.

But then Cornelius took a trip to Columbus, Ohio. To this day, he still recalls how his recruiting visit unfolded:

"Woody talked about academics 90% of our conversation. I thought that he wasn't interested in me because he wasn't talking football. And I told my mom, I said, 'I don't know about Ohio State, Mom. Coach Hayes never talked football. All he was talking about was school.'"

"My mom said, 'Bingo. That's the guy that I would like for you to play for because all these schools, all they're talking about is how good you're going to be for them when you get there and none of them are really concentrating on what you want to be in life. And Ohio State really went out of their way to talk academics to you.'"

Others, including Jimmy Raye, a black quarterback who had played for Michigan State, warned Green that if he chose OSU, they'd make him change positions.

He trusted Woody, though, who unlike coaches at the other schools recruiting him, did not promise he'd start the minute he stepped foot on campus. Woody told Corny he'd play him if he earned it, and that, along with his desire to get his degree, meant that his choice was easy.

"Flam" was Ohio State-bound.

While he swears that he was never arrogant, Cornelius did have a certain amount of swagger about him in college. He owned a colorful wardrobe, he boasted an impressively-sized Afro, and he drove around campus in a car with a "Flam 7" personalized license plate3.

His first year, though, he wasn't receiving much attention on the football field. In the 1973 Rose Bowl, a blowout loss to USC, he did see a little action, albeit as a kick returner.

That would soon change.

Check back next Friday for Part Two.

- 1 When he played for Ohio State, his last name was spelled "Greene", but shortly after his career ended, his family, 80% of which spelled it without the "e", decided that for consistency's sake, everyone would spell it "Green".

- 2 The two remain close to this day and are the godfather of each other's children.

- 3 People thought he knew the governor of Ohio because personalized license plates were not available in the state, when actually, they were DC tags.