Only Art Schlichter won more games as an Ohio State QB.

Only Art Schlichter won more games as an Ohio State QB.Seven years ago this month, a highly-sought after high school quarterback from Mission Viejo took a flight from Southern California to Columbus for a two-day official recruiting visit to Ohio State.

Upon arrival he was given the requisite nickel tour of campus and football facilities. He got to spend time with some of the players who had just brought home back-to-back Fiesta Bowl trophies.

He also got a strong sense of what Troy Smith and Justin Zwick were probably feeling as adversaries in what was already a highly-scrutinized battle for Ohio State's starting quarterback position several months before it had truly started.

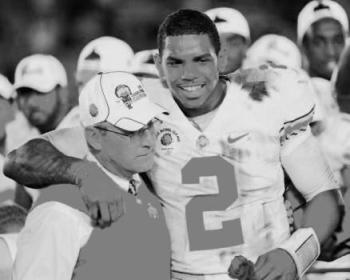

Near the conclusion of his visit he found himself at the Woody Hayes Athletic Center sitting in the head coach's office, right in front of his desk. Fourth-year boss Jim Tressel talked to him at length about his visit, his upcoming senior year in high school and what Ohio State had to offer to a player of his caliber.

Tressel recruiting pitches were always legendary in that they frequently strayed from the topic of football. As was his custom, no promises were made regarding playing time or the depth chart. The big picture, life's runway, fulfillment of potential and the navigation of a virtuous life surely made appearances as Tressel moved to close for business.

"You know," Tressel told the recruit, "the two most important people in the state of Ohio are the governor and the quarterback for Ohio State."

It was a brash statement to make about a state with well over 11 million residents and a GDP of almost half a trillion dollars. Eight US Presidents either hailed from or were born in Ohio.

There were and still are 12 other state universities beside Ohio State, six medical schools, numerous professional sports teams and six percent of the top 1000 publicly-traded companies in the country that are headquartered in Ohio.

Regardless of those realities, there was Ohio State's head coach telling a California kid that the head of the state government and his team's quarterback were the two most important people in the entire state. It's a bold declaration, if not sarcastic.

After a brief pause, Tressel provided clarification: "And the quarterback for Ohio State is number one." He wasn't kidding.

Feeding the beast

Nobody is born entitled. Entitlement is a product of cultivation. Shower any kid - talented, special or fiercely average - with enough adulation without properly pruning his ego and you'll create a monster.

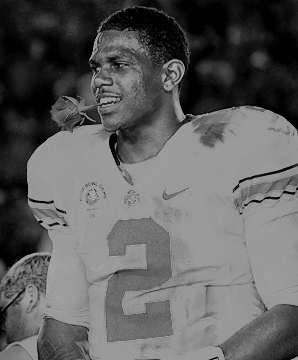

The MVP of two BCS victories would normally be granted sainthood.

The MVP of two BCS victories would normally be granted sainthood.When Mark Sanchez - the QB recruit and eventual USC Trojan who sat in Tressel's office that afternoon - recounted the story of his recruitment to ESPN the Magazine back in 2008 prior to his team's game against Ohio State, it was more than a just a taste of the Buckeye football-obsessed nature of Ohio. It was a glimpse into what would eventually be Tressel’s undoing.

Ohio State's quarterback may not be the second-most important person in Ohio, but he was always the most important person to Tressel. His preoccupation with signal callers has woven its way into the tapestry that now illustrates his rise and fall, from Ray Isaac delivering him his first I-AA national championship at Youngstown State, to Craig Krenzel running QB sneaks like cloaked daggers into Miami's heart, to Troy Smith making the move from back-up kick returner to runaway Heisman winner, to Pryor almost taking Tressel back to the brink of immortality.

The Buckeyes' quarterbacks coach Nick Siciliano might be the nicest guy on the staff and a worthy mentor, but the reality is that his hiring in 2005 - with a resume that shouldn't have even been considered for a program like Ohio State's - essentially allowed Tressel to serve the position himself while Joe Daniels battled health problems.

Siciliano was learning how to be a quarterbacks coach at Ohio State. Consider how absurd that is for a moment: He had Smith and Zwick to groom into junior quarterbacks coming off of what had been the worst season of the Tressel era. Don't kid yourself about who was closest to the Buckeye quarterbacks of the entire coaching staff: It wasn't Siciliano.

Pryor was not abruptly groomed into the brazen, entitled campus big shot that he was every day of his three years in Columbus. This was a kid who had his own action figure in high school. As a teenager he was friends with and employed by Ted Sarniak, one of the wealthier residents if not the wealthiest of Jeanette, who finds his name in the news with Pryor's predictable forfeiture of his final season of collegiate eligibility.

He arrived in Columbus entitled, and remained that way up until he announced his departure, seemingly oblivious or deliberately ignorant to the consequences of his actions all along the way.

If Pryor was going to be injected with the necessary humility and grace to be a successful adult on a stage with millions of dollars at stake, it was going to have to be off the field. Perhaps from the one coach who was closer to him than anyone else.

He leaves Ohio State with a 31-4 record, which is the second-most wins in school history by a quarterback only to Art Schlichter. This is when your brain can't help itself from making a connection between the disgraced star athlete of the day and Ohio State's most famous serial felon who has spent over a decade in 44 different prison cells.

He would have cruised by Schlichter's 36 wins before Columbus even considered the idea of getting chilly this season, and he very likely would have run all over the still-dismal Michigan Wolverine defense this November, making him the winningest quarterback in school history and the only one ever to go 4-0 in the game that matters most.

Ability didn't fail him. His lack of humility failed him. His 'mentor' Sarniak failed him. Ohio State failed him. His coach failed him, and he failed himself. It looks as though Pryor had his hand out from the moment he appeared on campus and did not withdraw it until he left for good yesterday.

Don't think too hard about where his sense of entitlement came from because it came from everywhere and from everyone. It started in Jeanette and continued in earnest in Columbus.

Most recently, it came from being told from day one that he was the most important person in Ohio, more important than the governor. Don't believe for a second that Tressel's pitch to Sanchez wasn't recycled for Pryor. Don't believe for a second that Braxton Miller wasn't told the same thing either.

You may be an Ohio State football fan for 10 more minutes or 80 more years, but you'll go to your grave wondering why Jim Tressel repeated rolled over and compromised his character, his $3.5 million salary and his dream job for a reckless star quarterback when neither his legacy or his institution needed him to be successful.

not too big to fail

One thing that is probably lost on short attention spans, casual observers and fans of teams that aren't the Buckeyes is that Pryor was never actually entitled on the field. As talented as he was just falling out of bed with his frame and natural ability, he never allowed anyone to outwork him. He played hurt. He played his ass off.

As often as they triumphed, Tressel and Pryor ultimately failed each other.

As often as they triumphed, Tressel and Pryor ultimately failed each other.It's been clear for awhile that his remarkable football discipline significantly outweighed his personal self-command, from his inability to drive responsibly (in loaner cars!) to his audacious disregard for basic NCAA rules.

Pryor knew exactly who he was, was aware of what he was capable of and he exploited it with total disregard for the framework that the arcane NCAA operates under.

Maurice Clarett served as a cautionary tale for this behavior, not just to Pryor and every other player who has been found or is under suspicion for improper benefits, but for Tressel himself. Ohio State football is bigger than Woody Hayes. It dwarfs Archie Griffin and every other Heisman winner.

What Clarett - and now Pryor - have quickly found out is that it does not matter how many games you win at Ohio State if you sully the name of the program. You have to leave it clean. Pride may be a deadly sin, but it is still the cornerstone of Buckeye fandom.

Win 31 games and two BCS bowls and you're a hero. Disgrace Ohio State and you're scrubbed from the empire. Pryor is effectively dead to Buckeye fans now. He isn't even polarizing anymore.

All he had to do was show restraint for four years in exchange for a lifetime of goodwill and guaranteed employment. It's an offer that anyone provided with competent mentoring should have gladly taken.

No one player is worth dishonoring what thousands of men have spent over a century building. No one player was worth compromising the program that Tressel had established over the past decade. At some point, Tressel himself somehow lost sight of that. Based on the number of proven and pending allegations against him, it's unclear if Pryor ever saw that at all.

After Ohio State lost the BCS title game to LSU in January of 2008, one of the very first people to buzz Tressel on his cell phone while he was still in the locker room digesting the loss was Pryor himself, then a still-uncommitted high school senior. He reassured his future coach that the Buckeyes would be back on that stage and successful with him under center.

Tressel had just gotten the Buckeyes back to the title game despite relatively weak lines on both sides of the ball and a statuesque, wholly ineffective Todd Boeckman under center. The most important person in the state of Ohio is Ohio State's quarterback, and Pryor was his top priority. Even though his formal signing with Ohio State was delayed for months, his destination was never in doubt.

Not even halfway through his tenure on campus, Pryor gave himself an intricate (and discounted) reminder of who he played for tattooed on his throwing arm; a Block O engulfed in Buckeye leaves. It will now serve as an permanent memento of what could have been.

Ironically, Pryor ultimately kept the promise that he made to Tressel that night over the phone in New Orleans: He did get Ohio State back on that stage in the Louisiana Superdome and the BCS, albeit not to the title game.

Tressel allowing Pryor to keep that promise instead of disciplining him - before and after the Tatgate episode - ultimately did them both in. Now Ohio State football is experiencing unprecedented turmoil with an NCAA investigation, relentless national and local media frenzy and an interim coach who doesn't seem to have permission to make public appearances yet. This probably isn't the bottom, either.

With Pryor now gone, it seems the least of the Buckeyes' troubles is the task of finding out who the most important person in Ohio is going to be next.