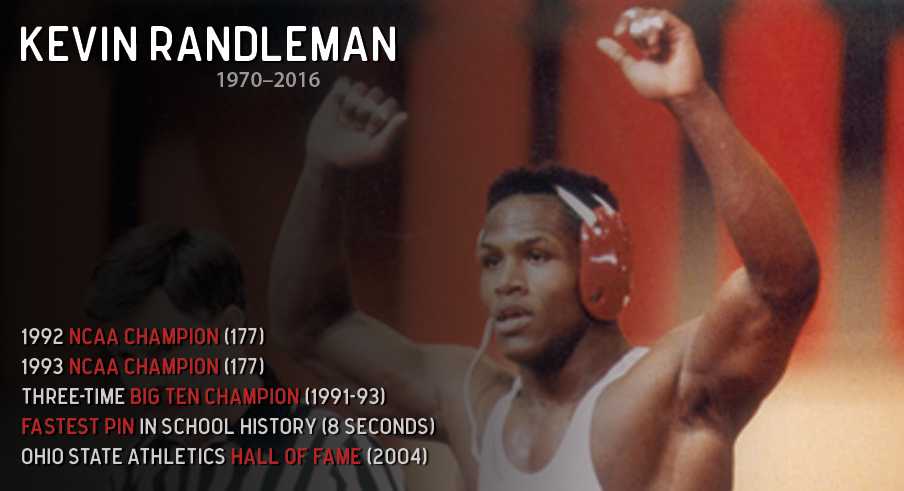

When Kevin Randleman passed away at 44 in San Diego in February, he did so as a former UFC heavyweight champion and mixed martial arts icon.

During his 15-year MMA career, Randleman fought on four continents against the the likes of Mirko “Cro Cop” Filipović, Chuck Liddell, Randy Couture, Fedor Emelianenko, and Quinton “Rampage” Jackson.

“The Monster” fought with the unrelenting ferocity of a man who faced tougher things in life than a professional fighter wanting to knock the consciousness from his opponent’s skull. That, along with his alien physique, cavalier attitude, and bleached-blond hair, earned him fans around the globe.

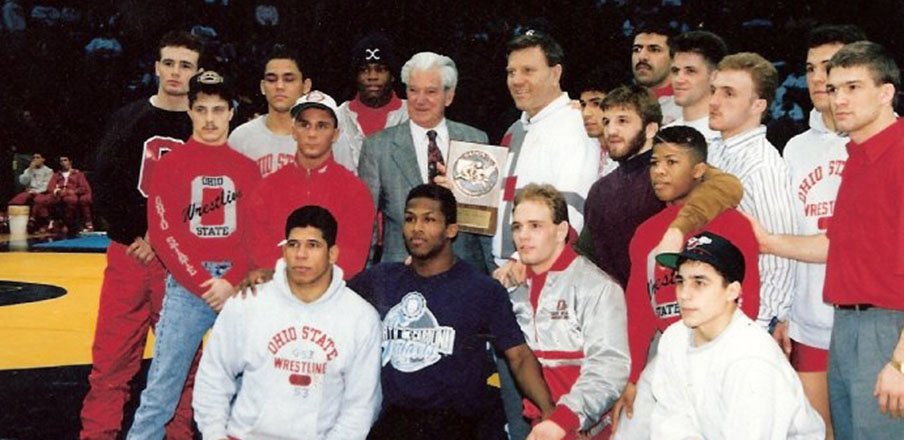

But when Randleman’s Ohio State wrestling family gathered at Forno Kitchen and Bar in Columbus' Short North in early March, his family, teammates, and friends only mentioned his pioneering career in passing.

That's because Randleman left behind a legacy that can't be measured with title belts or pay-per-view buys. To talk to those who knew him longest almost turns his professional fighting career into an insignificant hobby born of necessity.

Before The Monster, Randleman was one of 11 Randleman kids in Sandusky, Ohio, located on the banks of Lake Erie near Cedar Point, just two hours north of Columbus.

Randleman starred in football, track, and wrestling for Sandusky High School in the late eighties, but things never came easy for him.

He faced racial abuse from opposing fans—not that Sandusky was a racial safe harbor, either. That was where an off-duty cop put a loaded gun to the teenager’s head because he thought Randleman’s car outranked his skin.

Yet celestial circumstance and hardship never hardened his heart against humanity.

After fathering a son, Calvin, at 17, Randleman saw a Toledo football scholarship as his salvation. That, however, was before he met Ohio State wrestling coach Russ Hellickson.

Hellickson’s eyes misted over while describing Randleman. To the former coach, it was an honor to call Kevin his son. Their relationship started with Hellickson’s recruiting swing through Sandusky in 1989.

Hellickson pitched the soon-to-be state champion as the cornerstone of Ohio State’s first championship wrestling team… and a singlet the Buckeyes would wear the following season.

“Kevin's eyes lit up,” Hellickson recalled. “He said, ‘Can I keep it?’ I said, ‘No, that'd be a recruiting violation, but you can have one if you come to Ohio State.’”

Randleman became a Buckeye on the spot.

What was Hellickson getting, besides a mutant with a 4.3 40-yard dash and a 38-inch vertical leap? A young man who took loyalty to the grave.

“Did you see the ashes?” Hellickson asked, referring to the urn displayed at Randleman's Sandusky memorial. He left the Ohio State wrestling tattoo that covered his heart unmentioned.

Getting out of Sandusky wasn't the only hurdle to a better life. Randleman's genetics gifted him the ability to dominate high schoolers, but as former United States Marine and Ohio State heavyweight wrestler George Pardos said, "Everybody is good in college."

Randleman's first year proved eye-opening, as he struggled to adjust before his competitive instinct took over.

“He realized there were a lot better guys out there,” Pardos, who wrestled the smaller Randleman every week for four years, said. “So from his [first] year to [second] year, he became a beast.”

Hellickson credited former NCAA champions and OSU assistants Mark Coleman and Jim Jordan as the key teachers in giving the talented but technically unsound Randleman a front row seat to the dedication required for greatness. It proved to be a recipe for success given Randleman's addiction to the weight room.

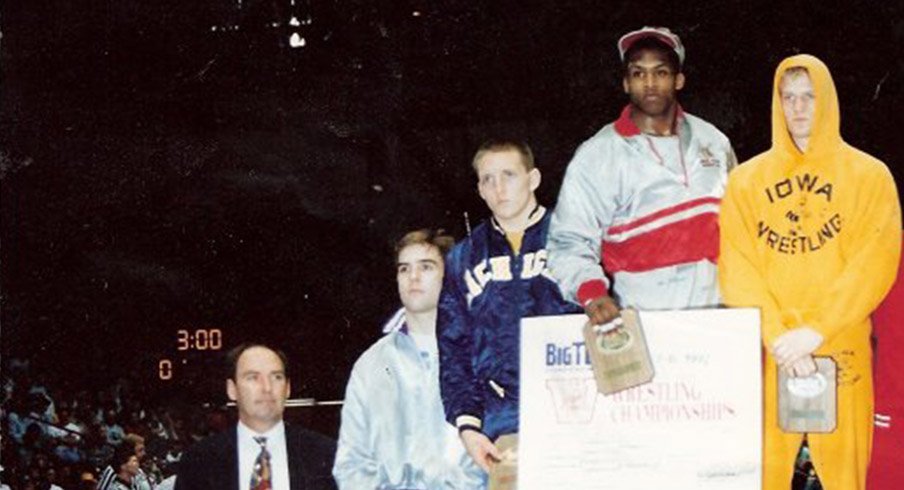

Randleman exploded onto the national scene in 1991 as a redshirt freshman, winning a Big Ten championship and reaching the NCAA championship at 167 pounds, where he met Iowa junior Mark Reiland.

The two split their previous matches. Reiland pinned Randleman earlier in the year but Randleman struck back at the Big Ten championships, 9-8, to become Ohio State’s first Big Ten champion since 1988.

Randleman went up early, scoring a takedown to go up 2-0, before Reiland escaped and scored his own takedown to stake himself to a 3-2 lead to at the end of the first period.

Reiland chose down to start the second period, and he got another escape to go up 4-2. The Hawkeye scored another takedown that period as his lead surged, 6-2. When Randleman attempted a reverse, Reiland caught him and threw him onto his back. Reiland earned three more points to make it 9-2 before pinning Randleman with one second left in the second period.

Pardos believes Randleman wouldn't have become a legend without suffering that defeat, particularly in that fashion. “It changed his perspective on things,” Pardos said.

Randleman's current regimen wasn't enough, but the gut-rending realization didn't crush the 20-year-old; it helped refocus him and fueled his competitive determination.

Will Knight, a three-time letterman at Ohio State, had to try out to make the wrestling team. As a freshman yet to prove his mettle, he may have been the first person outside the program to get a glimpse of Randleman's impending reckoning.

It came during a 2 p.m. political science class on the first day of fall quarter. Knight attended class in dress clothes, while Randleman— already The Man—showed up wearing a string tank-top.

“Afterwards, I walked up to him and said, ‘Hey, Kevin Randleman, I'm Will—’ and he cut me off,” Knight said. Randleman recognized him from a victory over a former Sandusky teammate at a prep tournament over two years prior.

“I was like, ‘You know why I came to Ohio State, Kevin? I saw you in the national finals.’”

Randleman didn't take it as a compliment.

“That shit ain't going to happen again,” he replied.

It didn't. Randleman's 1992 season would go down as one of the greatest individual seasons in Ohio State wrestling history.

Though Randleman enjoyed the spoils of being a successful athlete on a college campus, it never affected his training or standing within the team. He never missed a workout, and demanded the same dedication from those that trained with him.

Eric Smith, a two-time All-American and best man at Randleman's wedding, said injured teammates found ways to attend practice just to watch him wrestle because, “You always knew something crazy was going to happen.”

Randleman never took any day off—certainly not the days which he had to make weight.

“He had a really high metabolism. So Kevin would wait 'til the very last second to cut weight,” Smith said. “And Kevin was the only person on the team who could lose 12 pounds in an hour. He'd put on a sweatsuit and just sweat, sweat, sweat. An hour later he'd be underweight.”

He entered the 1992 Big Ten championship in top condition and undefeated at 177 pounds with an arsenal of takedowns and finishing moves honed over thousands of training hours. To defend his title, he'd have to go through Iowa senior and two-time All-American Bart Chelesvig… and more racial abuse.

“It [was] at Wisconsin but it [was] packed with Iowa fans,” Knight said. "And they were all yelling all sorts of racist stuff, but that was the wrong thing to do with him.”

Randleman dealt with racism his whole life. It was nothing new to him.

“It didn't rattle him. He was like, ‘Okay, now I'm going to embarrass your kid. I'm going to embarrass your guy now.’”

Randleman mauled Chelesvig from the jump, scoring a takedown one minute into the match to go ahead 2-0. Chelesvig earned a dubious escape call to end the first period only down a point.

Infuriated, Randleman chose down in the second, and “Granby rolled” into an escape seconds into the period to go up 3-1. Immediately thereafter, and with the alacrity of a scorpion’s strike, he leveled Chelesvig with a powerful double-leg takedown, 5-1.

Chelesvig earned another escape to make it 5-2 before getting deep on a single leg takedown, but Randleman’s strength thwarted the attempt.

Chelesvig chose down to start the third period, and escaped within 20 seconds to cut Randleman’s lead to 5-3. Randleman beared down in attempt to close out the championship.

Trailing 5-3 with a 1:30 left in the third period, the Hawkeyes hit their boiling point. Chelesvig, frustrated by a lack of a stalling call, tripped the Buckeye as he threw him off the mat.

A brouhaha erupted in the aftermath, but the cheap shot wasn't the problem. As Russ Hellickson went ballistic on legendary Iowa coach Dan Gable and Hawkeye fans, announcers said "debris" had been thrown on the mat.

Though the cameras didn't catch the deed, Knight saw it live.

“Somebody threw a can of dip from the stands at his head. I don't know what [was] more impressive, [Randleman] seeing it and ducking it or the guy throwing it that precise at his head,” Knight said.

No matter, Randleman vanquished Chelesvig a minute later. Unfortunately for the two-time Big Ten champion, he was still in hostile territory.

“We were back in the hallway, and this Iowa girl walked by and [slurred] him... all because he beat some Iowa boy,” Knight remembered. “Like, really? After all that? That's what it comes down to?”

Maybe for some Iowa fans, but not for Randleman.

Knight recalled a time the two were in Michigan's locker room at the 1992 NWCA National Duals in Ann Arbor. They came across Mark Reiland, the Hawkeye wrestler who pinned Randleman for the 1991 national championship. He and Randleman got along swimmingly.

“There was no animosity there,” Knight said, still somewhat mystified to this day.

The 1992 season culminated with the undefeated No.3-seeded Randleman facing Nebraska’s No. 5-seeded Corey Olson, who toppled the tournament’s No. 1 seed, Northern Iowa’s Rich Powers, in the semifinals.

Randleman took less than two periods to pin the man who left Nebraska as its second all-time falls leader, finishing the 1992 season with a staggering 42-0-3 record.

It was only his third year in the program.

Injuries plagued Randleman's junior campaign in 1993. He weathered a torn knee ligament all the way to the second round of the NCAA Championships at 177 pounds, where he faced Central Connecticut's Mark Frushone. He would leave the mat a Buckeye legend.

Calamity struck midway through the match when Randleman dislocated his jaw. Because the injury didn't occur as the result of an illegal maneuver, Randleman faced disqualification if he couldn't continue after an injury timeout.

There was only one play to make, at least for him. Randleman popped his jaw back into place without medical assistance, continued the match, and dropped Frushone, 10-5.

Kyle Rackney of Cornell gave the damaged Buckeye a stiff quarterfinals contest, but in the end he as well proved mortal. The Big Red wrestler fell 4-3.

Iowa's Ray Brinzer met Randleman in the semifinals, and he too proved no match for the reigning champ. Randleman disposed of him 9-6 to advance to the championship, broken bones and torn ligaments be damned.

There, Randleman faced a rematch with Nebraska's Olson. Despite the revenge factor and his foe's depleted status, the Cornhusker once again fell short. Randleman dispatched him, 5-2, for his second national championship in as many years.

To outsiders, Randleman was the king of the sport. What they didn’t know it would be Randleman's last official act as a Buckeye until his 2004 introduction into the Ohio State Athletics Hall of Fame.

Ohio State ruled Randleman academically ineligible for the 1992-93 season.

“The pressure of [becoming] a three-time national champ got to him,” Smith conceded. “That was the easy way out from competing. You can't compete if you're not eligible,” Smith said before noting Randleman's academic troubles had nothing to do with intelligence. “He wasn't a dumb guy. College was easy for him.”

Despite his championship glory, “Randlepoppy” was now a 22-year-old father with no source of income and no résumé outside the collegiate wrestling mat.

Randleman never hid from his self-inflicted wounds. “I did a lot of dumb shit at Ohio State,” he conceded in his last known interview earlier this year.

Severed from the team, Randleman could've returned to hustling Sandusky streets, becoming another one of America's rags-to-riches-to-rags story in the process. He chose perseverance.

Despite not wearing football pads in nearly a decade, Randleman resurfaced with the Arena Football League's St. Louis Stampede in 1995. The league shuttered the franchise after one season.

His life once again in financial limbo, his Ohio State wrestling family offered him the lifeline he needed when he got a call from his old mentor, Mark Coleman. Coleman’s plan involved the exploding mixed martial arts scene, into which Coleman had ventured after future WWE star Kurt Angle took his spot on the 1996 Olympic wrestling team.

“Oh shit, who I got to kill?”

“I was sitting at home in Sandusky, Ohio, and I had my oldest son, Calvin, with me, and we were watching the [1996] WWE SummerSlam or something,” Randleman recalled in 2013. “Mark Coleman called me and asked me if I wanted to fight, and I said, ‘Nah, not really.’ And then he said, ‘$30,000.’ So I said, ‘Oh shit, who I got to kill?’”

As it turned out, Randleman didn't have to kill anyone. He just had to win three fights in a single night, which was no spectacular feat given his history.

A few months later—October 22nd, 1996 to be specific—it took Randleman under 17 minutes to dispose of three professional fighters at Universal Vale Tudo Fighting 4 in Brazil. He submitted the more experienced Dan Bobish with a fusillade of punches to win the tournament.

A monster was born.

George Pardos fondly recalled a time at a road match when he was holding Randleman's toddler son, Calvin. They had all just eaten a home-cooked meal, and Calvin spit up on him.

“Kevin ran over screaming, ‘George, what are you doing torturing my son?’” Pardos said, laughing.

Eric Smith will cherish a brotherly text conversation the two had only a week before Randleman's passing.

“When people pass away, other people will say, ‘I wish I would've said this. I wish I would've said that,’” Smith said. “I'll always remember is his energy, and how I got to tell him how much he means to me. That means a lot.”

To Will Knight, Randleman's story of not succumbing to adversity inspires the at-risk youth he coaches in Shaker Heights, Ohio. “He did the best the could with the adversity in his life, and he was determined to not let it bring him down.”

Randleman came to Ohio State as a boy and left a man. We would not know him as we do today if he had chosen Toledo football over Ohio State wrestling.

“When I think of Ohio State, I think of the greatest university in the world,” Randleman said in 2015. “I met and am friends with some of the greatest people I've ever known while I was there. A black kid from Sandusky, Ohio, you just don't think you will get the opportunity to represent the school that in Ohio, is the only thing that walks.”

He shouldn’t have been surprised. Randleman took a short hand from life but chose to surround himself with good people that helped him get where he needed be. Add in his natural work ethic, and it’s a story that reads like destiny.

Maybe it was.

You can donate to the Kevin Randleman Memorial Fund. Proceeds support Randleman's surviving family and The Monster Wrestling Academy in Las Vegas.