(Apologies to those hoping to discuss Marengo this week- I’ll try to get that post up tomorrow, if things work out well. I think you’ll agree that this post is rather appropriate under the circumstances. If you want to read more military history topics, check out the archive here.)

If I’ve timed this right, this post will go up at about the same time that, 100 years ago, the Germans ended their preliminary bombardment at Verdun and went over the top. Right now, 100 years ago, along a 19 mile front, the Germans have spent the last several hours firing 1,000,000 shells into French positions- for the past hour, the rate of fire has been so intense that it would be impossible to tell individual explosions. It would just sound like thunder. Thunder so loud, you could hear it 100 miles away. 100,000 Germans, 100 years ago, were rising out of their trenches and charging for French lines.

Verdun is, no longer, the largest battle in human history (Stalingrad is), nor the bloodiest (Also Stalingrad), nor the longest (Sarajevo). At one point, however, it was all of those things. 2,400,000 men fought at Verdun. Out of those that went in, 1 in 8 died. 1 in 2.5 would be wounded severely enough to need medical attention. To put this in perspective, by the time your taxes are due, there will be more men killed or wounded at Verdun than there are seats in Ohio Stadium.

In English, we refer to this as the battle of Verdun. The French, however, refer to it as L’Enfer de Verdun. The Germans, Die Hoelle der Verdun. The both translate to the same thing: The Hell of Verdun. This title was not given glibly. Any combat veteran will tell you that war is hell. The combat on the Western Front was horrific- and yet, everyone recognized Verdun was different. When the Nazis ordered veteran organizations to expel their Jewish members, many of them refused to expel Verdun veterans, and filed formal complaints about the law. The French struck special medals for the veterans of the battle. I think it’s important we take a moment today to understand the battle- one that shaped our world as much, if not more, than any other.

The German Plan for Verdun

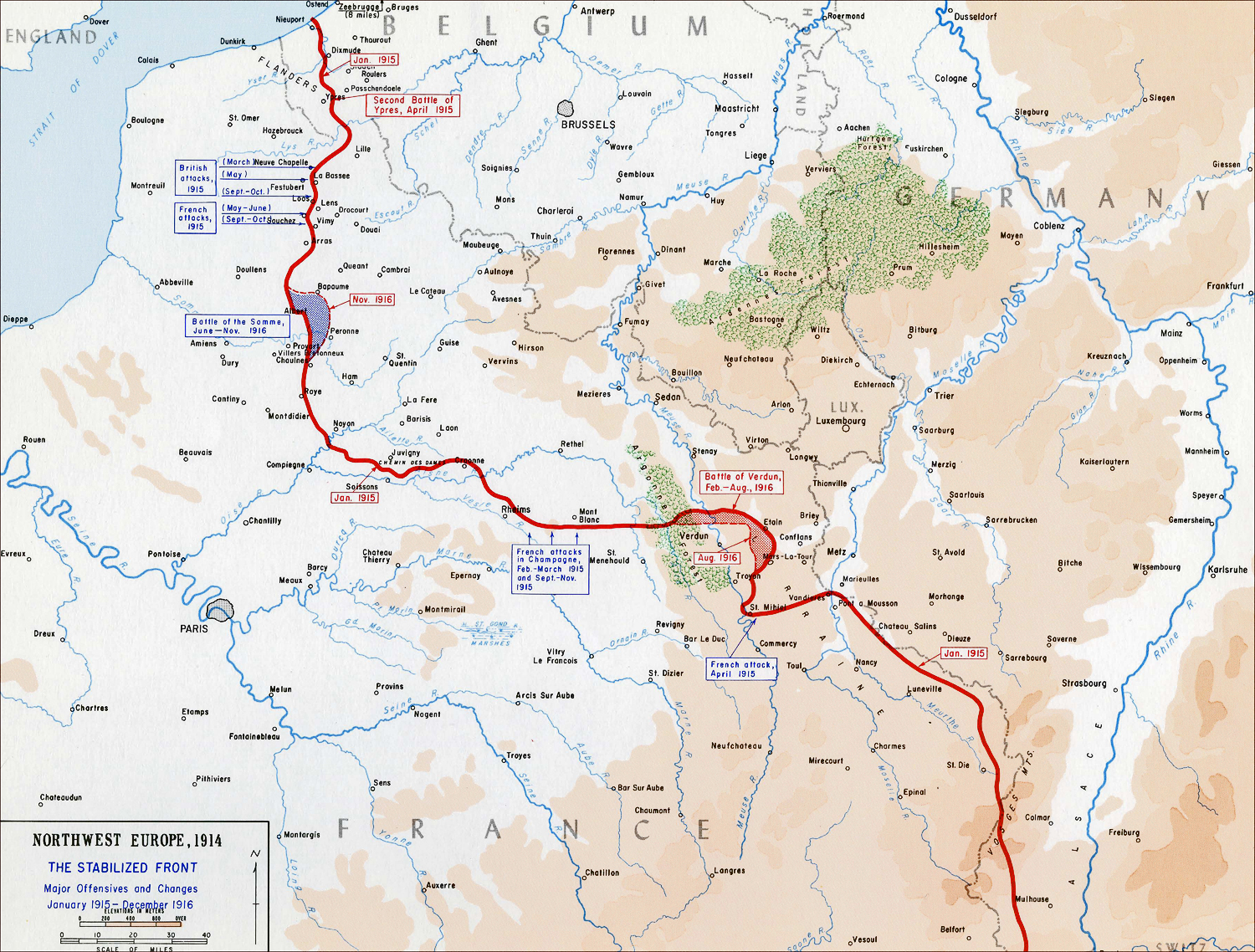

After the First Battle of the Marne in 1914, the chief German commander, Helmuth von Moltke, was relieved, and replaced by Erich von Falkenhayn. Falkenhayn spent the remainder of 1914 organizing the German retreat from the Marne and the establishment of the German trench lines. In 1915, he guided the Germans through a major offensive on the Western Front, the 2nd Battle of Ypres, as well as a significant defense in the Champagne-Artois area, where the British and French launched massive offensives. These battles in 1914 and 1915 convinced Falkenhayn that there was no real way to make a massive breakthrough against the trench lines of the Western Front. The trenches were so costly and time consuming to clear that momentum in the attack broke down. Rail lines made it too easy to move reserves, and industrial production provided too many supplies, to make local breakouts possible. Even poison gas wouldn’t kill fast enough to facilitate a breakout.

So, Falkenhayn decided to target the one resource that the French couldn’t produce on an industrial scale: men. Rather than attempt a massive breakthrough, he would launch a limited offensive against a point the French could not afford to lose. The French would counterattack into strongly held German positions, and, eventually, the French population would be bled white. When there were no more Frenchmen left, Germany would have won the war.

There was even an obvious point to attack: the Fortress of Verdun. Verdun has been a fortress for as long as it has existed. It was founded… sometime around the fall of the Roman Empire, as a Gaulic fortress. Throughout the Middle Ages, the fortifications in the area improved steadily, and, in the 1600s, Vauban, the great French engineer, turned the area into a massive fortified zone. Verdun was the last French fortress to fall in the Franco-Prussian war. By World War I, the city was surrounded two rings of polygonal fortresses, each providing mutually supporting artillery and machine gun fires. 16 fortresses made the first ring, six the second, and, finally, in the city itself, a massive citadel. The city also served as a massive rail and road junction, and was a major strategic movement hub in 1914 and 1915.

Fort Douamount, a polygonal fort.

However, by 1916, the Verdun Fortified Zone was a shadow of its former self. In order to support the French offensives of 1915, the French had stripped hundreds of heavy guns, thousands of machine guns, and tens of thousands of men from the fortresses, leaving them weak. Also, Verdun stood at a vulnerable position in the French line- essentially, a kink where the line formed a pocket around the city and fortified zone. If the Germans managed to collapse this pocket, it would threaten the entire Allied line. It would cut vital lines of communication, supply and reinforcement. The French would have no choice but to keep the Germans from capturing Verdun. However, there were few French there to defend it. Falkenhayn figured he could attack into the weakened area, take control of it and, using the fortresses and high ground around the city, force the French to launch massive, futile offensives to retake the area, and kill them until the war ended.

Strategic Position, Western Front

The Opening of the Battle

The Germans undertook extensive preparations for the battle. They laid several new lines of railroad tracks, which led to fortified, underground stations near the trenches to facilitate movement of reserves into the front. They laid in millions of tons of food, ammunition and other supplies, including 2,000,000 shells- enough to last the first few days, at least. Thousands of miles of telephone wire ran back to the batteries, while trenches and dugouts went up to protect troops in assembly areas. Several armories also went up to repair artillery and other weapons in the fighting area. German factories went into overdrive to produce enough supplies for the offensive, and would continue for the rest of the year, while local commanders at the front developed a detailed fire plan and plan of attack.

These preparations were impossible for the French to miss, and, so, in the month before the attack, they began to prepare. Before the battle opened, Joffre, the French overall commander, believed that the German preparations were for a diversionary attack, and decided against committing a large portion of the French strategic reserve. He did send another three divisions to Verdun before the attack, and alerted another 10 to move out. The French commanders on the scene, Noel de Castelnau, got into an argument with his superior, Fernand de Langle de Cary, over where to establish the defense. De Cary wanted to effectively abandon the eastern bank of the Meuse, and oppose the Germans at the river. Castelnau, however, opted to fortify the eastern bank, connecting the fortresses into three lines of trenches.

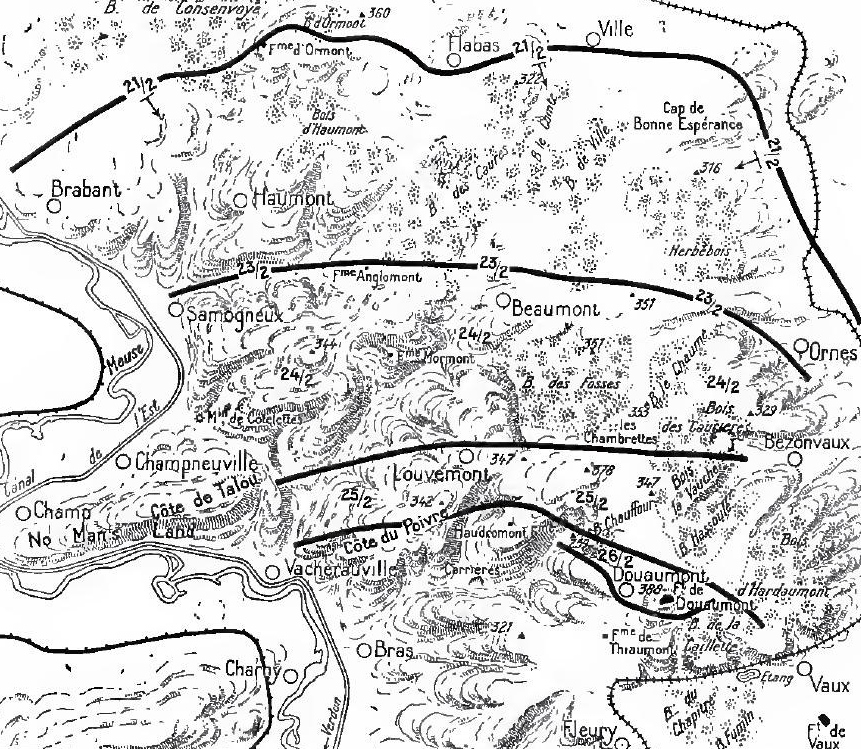

The German attack went well at first. Artillery crashed into the first French lines, while heavier guns bombarded into the French rear, attacking reserve assembly formations. Other batteries waited for French artillery to respond, then bombarded those batteries with shells filled with chlorine and phosgene. The bombardment let up at noon, to encourage the French to expose themselves and allow for airplanes to assess the damage. The bombardment resumed until 1600 on February 21st, when the German first wave began the attack, spearheaded by the first flamethrower units deployed in combat, which were supported by picked men armed with grenades and pistols- some of the earliest storm troopers.

By the 22nd, the Germans had cleared the first French line, and, by the 24th, the second. At this point, it was clear that this was the main German strategic effort, and Castelnau called for more reinforcements from the French Reserve. Joffre sent Phillipe Petain and the 2nd French Army to relieve Verdun. It couldn’t arrive fast enough: on the 26th, the Germans captured Fort Douaumont, the centerpiece of the French final “Line of Resistance,” and began turning to close the pocket around the French remaining east of the Meuse. However, the German attacks began to slow. The offensive brought the Germans closer to French guns on the West bank of the Meuse, which could support French positions with little threat from German guns. Also, the weather warmed, thawing the ground and turning it into a well churned slurry of mud. Finally, the German artillery was completely worn out by the volume of fighting, and needed repair.

The Second Phase

There was a relative lull in the fighting until March 6th, when Falkenhayn resumed the attack, this time against French forces on the northwestern side of the pocket, on the west bank of the Meuse. This attack was aimed at a series of wooded hills between Bethancourt and Chattancourt that overlooked French artillery positions. By seizing them, Falkenhayn hoped to bring up more artillery to bombard the French guns, freeing up his men on the east bank to resume their advances. However, the lull in the fighting had allowed many of the men in the 2nd Army to arrive and dig in. Between March 6th and April 7th, the wooded hills and villages of the area exchanged hands several times before, at a cost of 80,000 casualties.

At this point, Falkenhayn was prepared to call off the whole offensive as useless. He hadn’t gotten the position that he wanted, and French reinforcements had arrived too quickly. However, Crown Prince Wilhelm, commanding the German forces in the area, asked for more men, and convinced Falkenhayn that the French were close to collapse in the area. Local German commanders were authorized throughout April and May to launch attacks against French positions in order to encourage French counterattacks, which would be met with heavy firepower. On May 22nd, Robert Nivelle, who commanded the defenses on the Eastern bank, launched a counterattack to retake Fort Douaumont, which failed in a bloody repulse. This encouraged the Germans to continue.

The Third Phase

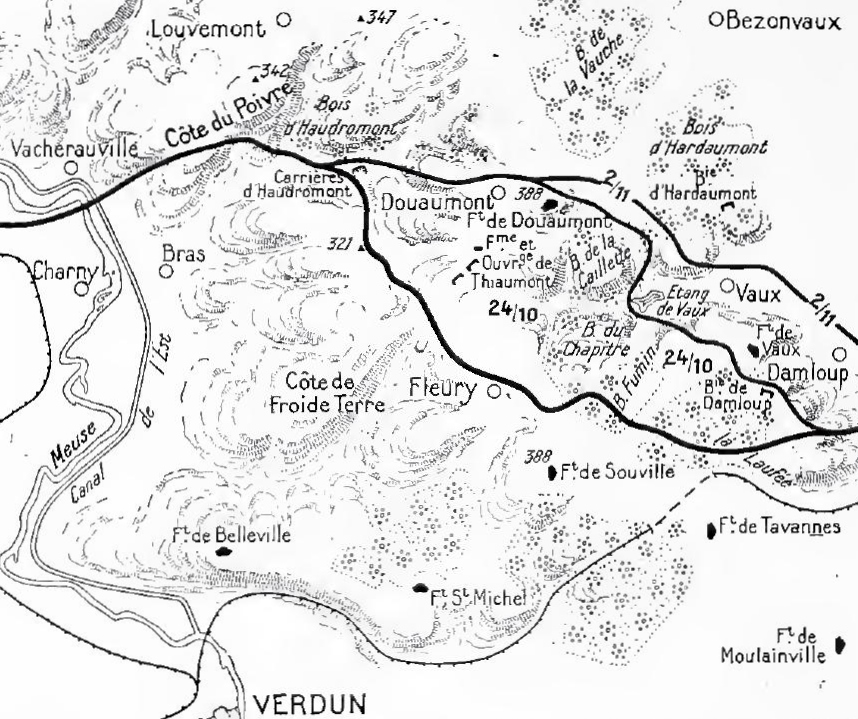

The Germans launched an attack against Fort Vaux, at the southern flank of the French position, taking it after three days and three thousand dead. The news of Fort Vaux’s fall led to the French manning the final line of defense around Verdun, the “Line of Panic,” and bringing the citadel to full readiness. The Germans continued attacking, this time attacking towards Fort Souville, the centerpiece of the Line of Panic. These attacks faltered at the end of June, when Germans ran out of water, and, more importantly, phosgene. The French counterattacked again, driving the Germans back, only to be pushed back once again themselves. The Fluery Ridgeline, the main bone of contention in the area, would change hands 16 times between June and August, 1916.

It was during these attacks that a company of French troops, about 100 men, were holding a cut off trench against all hope. The Germans launched a furious bombardment against the French position, while the men huddled in the trench. They left their rifles up on the parapet of the trench, bayonets fixed, waiting for the German infantry to come. They never saw them, though. The bombardment was so intense that all hundred men were buried alive. Their grave markers- the fixed bayonets of their rifles sticking out of the ground- were discovered after the war, becoming the famous Trench of Bayonets.

On June 9th, the Germans prepared another attack, this time focused on Fort Souville. 300,000 shells landed on the Fort, including 500 from the 14-inch railroad cannon, Langer Max, and tens of thousands of newly arrived Phosgene shells. On the 11th, thousands of Germans swarmed towards the fort, breaking into the walls. French machine gunners manned the citadel, sweeping the Germans off the walls before being wiped out. However, a rapid French counterattack returned the Fort to French control on the 12rth. On the 15th, the French launched a major counterattack, but this attack was routed with heavy losses and no gain. The attack proved the high water mark of the German attack, but their overall strategy was, in many ways, still a go.

The Fourth Phase

The German pressure on Verdun came close, several times, to breaking the French army before the attack on Fort Souville. The French went to their allies, demanding that they take action to relieve the pressure on Verdun. These demands led to action on both the Western and Eastern Front. On June 4th, the Russians launched a massive offensive, the Brusilov Offensive, against the Austrians While initially successful, inflicting heavy casualties on the Austrians, the German counterattack- using divisions pulled out of the reserves earmarked for Verdun- smashed the Russian army later that summer, leading, in 1917, to the end of the Russian Empire, the Bolsehvik Revolution, and the eventual exit of the Russians from the war. The offensive left a million dead in its wake. On July 1st, the British launched their own offensive across the Somme River. The poorly trained, but enthusiastic, British volunteers went over the top- 100,000 of them on the first day. By the end of July 1st, 20,000 of them would be dead, and 40,000 wounded for a few hundred yards of ground. Despite this, the offensive continued, and, in the end, 300,000 men- half Allied, half German, lay dead on the five miles of land between the start and end points of the battle. 700,000 were wounded.

The enormous pressure on Verdun was increased by the weakness of French lines of supply. The early German successes had cut the rail lines, and most of the roads, into Verdun. German artillery made it impossible to move supplies up the Meuse to Verdun. In the end, only one road lay open between Bar-le-Duc, the main French railhead in the region, and Verdun. Half a million men marched down the road to the battle. Every day, trucks and a small rail road moved thousands of tons of supplies. It took 9,000 men, working day and night to keep the trucks and trains moving, either directing traffic or fixing the machines. Another 16,000 men worked to keep the road open, fixing the potholes and, effectively, repaving the road over and over again. The road became known to the French as the Voie Sacree- the Sacred Way.

The fight for Fort Souville left both sides exhausted, and required some rest and reorganization. On August 1st, the Germans made another attack, which the French repulsed. The French counterattacked throughout the month of August and into early September, regaining much of the ground the Germans had taken in the early summer, and retaking Fleury for the last time. However, the effort left the French so exhausted that they, and the Germans effectively, suspended operations for nearly a month.

On October 20th, the French began the First Offensive Battle of Verdun, aimed at Fort Douaumont, now the centerpiece of the main German line of defense. The French had replaced large numbers of weary veterans with fresh troops, and reorganized their men into forces with mixed armaments- riflemen, automatic riflemen, and grenadiers. These troops attacked, following closely behind a creeping barrage into German positions. After a six day bombardment, the French advanced on Douaumont. On October 24th, French Marines stormed the fort, retaking it. An assault on Fort Vaux the next day failed, so the French artillery shifted to Vaux, bombarding it into extinction. On November 2nd, the French marched into the destroyed place without a shot.

Fort Douaumont upon it’s recapture

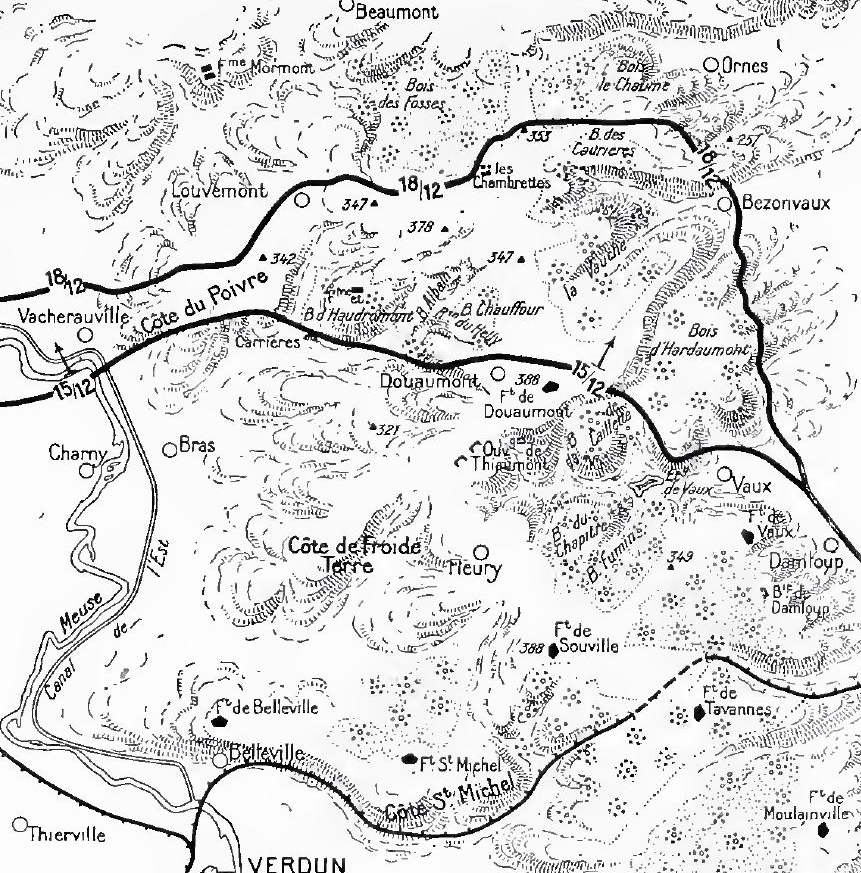

The final attacks came on December 15th, when the French opened a wide bombardment on the German positions. In the end, the Germans had had enough, and the French attack met little resistance as it opened and drove back the Germans. By the 17th, the Germans had been forced back to their starting positions of February, with, effectively, no ground gained by either side in the battle. Winter closed in on the battlefield, suspending operations and effectively ending the battle.

After the Battle

The fighting around Verdun continued after the Battle effectively ended. In August and September 1917, the French made several attacks in the area, pushing back German positions to clear out some room near the fortress, and in support of the French Offensive of 1917- one of the few successes of that effort. In 1918, the Americans, as part of the larger Meuse-Argonne offensive, launched several attacks against German positions on the Western bank of the Meuse, pushing the Germans away from Verdun in their final retreat. However, as you might expect, the continued fighting around the city meant that the war continued- it was hardly the decisive effort the Germans hoped for. In fact, for the most part, the battle had little impact on the war beyond being a rehearsal for later actions.

After the war, the French faced an unprecedented ecological disaster. Tens of thousands of shells fired into the Verdun region failed to explode, making the area dangerous. The deployment of bullets, poison gas, and other munitions deposited heavy metals in to the ground, poising plants and animals that travelled there. Hundreds of thousands of bodies, man and animal, lay rotting on the ground. The French government, after the war, declared the Verdun Battlefield a Red Zone- a place where no one was allowed to go because of the danger. Since the war ended, the French government has tried to clean up the area around Verdun. At the current rate of reclamation, the French government believes the area might be safe to live in sometime in the next 700 years- well after humans will be able to live and work safely in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone.

View from Fort Douaumont, 2005

After the war, in addition to the effort to survey and reclaim the land, there was an effort to deal with the dead. A battle as large as Verdun deserves a memorial, and the French government built one to house the dead. They built a large cemetery on the ground of Fort Douaumont, as a memorial to the French and Germans who fought there. The cemetery contains 15,000 indentified remains, that, for whatever reason, were not returned to their home towns once found. They’re laid out in row on row of crosses for the Christians, with a small section of the cemetery facing Mecca for the hundreds of Muslim dead.

The problem with Verdun, though, is what do you with all the unidentified remains? To house them, the French converted the citadel of Fort Douaumont into an Ossuary, a series of vaults to hold the remains. As you tour the battlefield, you’ll find boxes situated around the trails that have been cleared. Those are for any bones you find on your tour of the field. People still find plenty, and deposit them in the boxes. (Don’t pick up any shells you find, please) Those eventually find their way in to the Ossuary, which currently hold the remains of 130,000 men, their names known only to God.

Douaumont has been the site of most of the commemorations of the battle itself throughout the years. The most famous moment in these ceremonies came in 1984. That year, Francois Mitterand, President of France, and Helmut Kohl, Chancellor of Germany presented wreaths in a cold, driving rain. They then held hands for several minutes as a symbol of Franco-German reconciliation.

Maybe something good came of it, after all.