Welcome back- I hope everyone enjoyed the start of bowl season as much as I did. I think that, as we enjoy the last football of the year, we should enjoy a little military history, too.

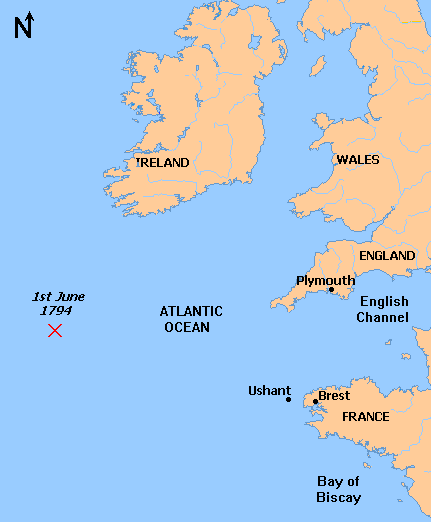

This week, we’ll head from the land to the sea to examine the first major naval battle of the war- the Glorious First of June. It’s an odd name for a battle, but, A) the British got to name it, and B) there’s really no point of land close to where the lines met in the fight. In fact, it’s one of the earliest battles to be fought, as far as I know, out at sea and out of sight of land. But, before we talk about this battle, we should talk about some basic facts of war at sea on the Age of Sail.

Wooden Ships, Iron Men

In the mid 1600s, ships underwent a series of rapid transformations, particularly in the Netherlands and England. In this time, as these two countries fought a series of mostly naval wars, often against each other, they began redesigning their galleons in order to make them more effective combatants. Galleons were large ships, with three masts, tall castles fore and aft, carrying some cannon and with plenty of cargo room. They were kind of catch-all ships, capable of firing broadsides of cannon (Mostly against Indian ships), fighting boarding actions against other ships (mostly against European ships) and carry lots of cargo. (Because that’s what ships do.) The tall castles tended to make them hard to maneuver, but were useful in combat, and were slow, because of their wide beam, but made money, because they could haul cargo. When galleons fought, they usually sailed into each other in bunches, found some other ship to fight, and fired a few cannon and tried to board or shoot the other ship’s crew.

Galleon Fight!

The Dutch and the English began designing dedicated men of war in the early to mid 1600s. They took their galleons, cut down their castles- particularly the forecastle- and began loading up cannon on the broadside. These ships were very vulnerable to attack across the bow or stern, where they could both offer little reply, and presented an enfiladed target to the enemy. These shots, known as raking shots, could also easily dismast a ship, or disable a rudder. Given this weakness, and given the fact that their firepower was concentrated down the broadside, it wasn’t long that admirals in the Dutch and English navies began sailing their ships in line astern, effectively forming columns of ships. This line of ships gave these new large men-o-war their name: Ships of the Line of Battle, often shorted to Ships of the Line.

Ship of the Line

By the Seven Years War in the mid 1700s, the design of Ships of the Line had been pretty well hammered out. The most common Ship of the Line was the 74 Gun ship. These were about 170 feet long, displaced 2,000 to 3,000 tons, with crews of 500-800. They carried cannon on two decks- 36-pounders on the lower deck, 24-pounders on the upper deck, plus smaller guns on the upper works, coming to a total of about 74 guns. This is a massive amount of firepower- on land, a 12-pound gun in the era was considered heavy field artillery, 24 pounders were siege guns, and 36-pounders only existed in fortresses. A well-equipped army might have as many cannon as two 74s, all much, much smaller.

Under the British organization, Ships of the Line formed into fleets assigned to different areas. Ships of the Line would only sail alone in the safest of waters, since they were still vulnerable to lucky shots across their bows or sterns. Each fleet would then divide into three squadrons: the van, commanded by the fleet’s Vice-Admiral, the Center, commanded by the Admiral in command of the fleet, and the Rear, commanded by the junior admiral, aptly titled the Rear Admiral. The Vice and Rear admirals would sail on larger ships, with a third gundeck. These carried around 90 guns. The admiral commanding the fleet would sail on a First Rate ship, with 100 or more guns. (HMS Victory, Nelson’s flagship at Trafalgar, was 104- but the largest ship in that battle was Santasima Trinidad, with 140 guns.)

Battles using these tactics were generally stately affairs. The opposing fleets would line up, pass alongside at a meandering 3-4 knots, blast away for a few hours, then usually peel off since it was getting late and they had to be home for dinner. Ships that were damaged were usually able to limp off, though occasionally a few would be left behind and unable to get a tow back to port. Most serious victories of the era, such as Quiberon Bay, came when one side couldn’t hold formation for some reason or another. Given her geographic position, a draw was good enough for the British when they fought the French or the Dutch in the Atlantic, and could usually provide enough weight to keep the Spanish from fighting. Most of the interesting battles took place the few times when the British tangled with the French Mediterranean fleets.

The Battle of the Saintes, 1782.

In all honestly, the Battle of the Saints deserves more consideration than it’s going to get here. It’s fundamentally one of the most important battles in the history of the world- in one morning, the British nailed the coffin shut on France’s hopes of world dominion, solidifying their overseas trading empire from the greatest threat it had seen since the Dutch burned the British fleet in the Thames River. The short understanding of the battle’s prelude is this: The Comte de Grasse, fresh of his victory over the British fleet at the Battle of the Chesapeake the year before, and building off his victories in 1779 and 1780, seizing major sugar islands in the Caribbean, set his sights on the lynchpin of the British Empire’s sugar trade- Jamaica. Jamaica made more money for the British in a year than the 13 Colonies would in nearly a decade.

De Grasse sailed with a powerful fleet of 33 of the line escorting a convoy of 15,000 men bound to besiege Kingston. Defending Jamaica was George Rodney, commanding 35 of the line. From the 9th to the 12th of June, the two fleets danced around each other, exchanging fire, then retreating to repair, while keeping each other in sight. On the morning of the 12th, a French straggler, Zele, of 74 guns, came into range of a group of British ships. Hoping to save her, de Grasse turned to cut off pursuit of Zele, then duck away. However, unbeknownst to him, the British ships had copper sheathing on their hulls, and were much more resistant to barnacle growth than his own, giving the British an advantage in speed de Grasse did not anticipate, which allowed Rodney to close with and force de Grasse to give battle at about 8:30 in the morning.

Despite the unanticipated battle, de Grasse mostly had the setup he wanted. The fleets would pass in opposite directions, limiting engagement time as the ships passed alongside. The wind stood out to port of the French line, with the British along the starboard, blowing the British off the French line, and French smoke onto the British ships. The French preferred to keep the range open, since their gunners were better, but slower, than the British.

However, as the ships had just about passed halfway through the promenade of the battle, at about 9:20, the wind shifted suddenly. Rodney, absolutely needing a decision- a draw would eventually allow the French to reach Kingston and debark- took a massive risk, and did the one thing you absolutely never, ever, under pain of death, did in a sea fight- he turned part of his line into the French line, exposing them to French fire in an effort to cut out part of the French fleet and concentrate fire upon it.

The maneuver paid off. The British center and rear effectively cut the French center off from their van and rear. The winds would not allow the French to double back, while Rodney could pound and destroy the French center. De Grasse’s flag, Ville de Paris, suffered horrendous fire and struck, making de Grasse a prisoner. Cesar exploded, and two more French ships of the line surrendered. The rest of the fleet broke and scattered, running for Guadaloupe.

Needless to say, after such a great victory, there were calls to sack and court martial Rodney for not winning by enough. I guess some 11W commenters have had very long lives.

The Glorious First of June

But, wait a minute, I thought we were talking about a battle in 1794, not 1782! Well, we needed to cover the Saintes so that we could discuss the Glorious First of June, since, as we shall see, what Rodney did in a risky effort, Lord Howe would attempt to do on purpose.

The reason for the battle itself lay in the increasing problems faced by the Committee for Public Safety in France. The political upheavals of 1792 and 1793 had ruined French crops, and prevented the movement of food around France. In the end, the Committee for Public Safety’s claim to authority came from two separate promises: first, and rather loftily, to save the revolution from internal rebellion and external invasion. Second, and more practically, the Committee promised to feed the starving poor of France’s cities. They had had some success in the first goal- French forces had largely pushed the Coalition out of France in 1793, recaptured Toulon, went on the offensive in the Vendee, and mobilized a million men into the army. The second, however, was proving far more difficult. While the Committee had managed to chase off or execute every landholding nobleman and clergyman it could get its hands on, the lands owned by the Church and those nobles were still in limbo, and distributing these lands was proving difficult in the middle of the upheaval. The Committee, to pay for the war, switched to an inflationary fiat currency, driving the price of food hire. To support their main supporters as the price of food rose as the currency collapsed, the Committee set the price controls for most goods in France, on pain of death. Since the price set for food was drastically low, it became impossible for anyone to sell food and not lose all their money. So, the Committee rounded up food wholesalers and warehousers, confiscated their goods, and executed them for hoarding. After this, no one would buy or sell food, making it all worse.

To solve the immediate food problem, the Committee decided to buy as much food as it could. French possessions in North America were tapped for as much food as they could produce. Backroom deals were made in Central and South America to get food under the table from Spanish colonies. The French ambassadors to the US called in every marker they had, asking the US government to help organize a grain convoy and the sale of grain to the French to repay the French for their help in the American Revolution. (Nevermind that that debt was owed to a now dead king.) In the end, hundreds of ships assembled in the Chesapeake, and, in April, sailed for France, hoping to run the gauntlet of the British Channel Squadron.

The French Atlantic Squadron snuck out from the blockade laid by the British, heading to sea late in May, hoping to raid some convoys themselves before meeting up with the French grain convoy. Shortly after the French left port, Howe and the British set sail to go find them. However, with the French far out to sea, Howe would need some luck to find them. Luck found Howe, and Howe found a French straggler trying to catch up with the main force, and followed her to the main body. On May 28th, Howe attempted to close with the French, but could only exchange some fire and damage a French ship. On the 29th, Villaret, the French commander, received word that the grain convoy was close. He decided to turn away from the convoy, hoping Howe would follow him and try and force a battle. Howe was too happy to comply, and tried to chase Villaret down. Howe signaled for his line to turn in and cut the French in half, as Rodney had at the Saintes, but the lead ship either missed the signal, or her captain refused to follow the order. The two sides battered each other for a while, then fell off out of range with many ships damaged. For the next two days, the ships made repairs while a fog made fighting more or less impossible.

The fighting had allowed Howe to get upwind of his enemy, meaning he could attack at will if the French would stand. When the fog cleared on the morning of June 1st, Howe ordered his attack. However, instead of turning his line into the French line, Howe decided to have each ship turn in on its own, sail through the French line, firing away, then reform the line on the leeward side of the French formation to cut off their escape.

This plan seemed foolproof, but, things did not go according to plan. Howe signaled his plan into action early in the morning of June 1st, but not all his ships reacted immediately. Only a about a quarter of his 25 ships of the line turned on command and set full sail into the French. The others lagged behind at various rates of speed, either turning late, setting the wrong sail, or, refusing to turn in at all and staying at long range. This led to the British to approach piecemeal into the French, who held their line and began to open fire against the British, who, their bows to the enemy, could not reply to. However, this was not de Grasse’s French Navy. Just like the army, the French navy was officered by nobles, who had been driven out by the revolution. Unable to pay the army regularly, the Committee had decided to short the navy’s pay drastically, leading men to jump ship when they could. Given that the pay was quite irregular, the only thing the Committee could do to make it up to the sailors was starve them, and so they did that, too. Hungry, broke, led by incompetents, the petty officers mutinied in 1793. This led to a massive wave of executions of mutineers, guys who looked vaguely noble, complainers, moderately competent people, and anyone who said anything about it, further weakening the men of the French navy. The French squadron had sailed woefully shorthanded, and poorly trained gunners could not take advantage of the ragged advance of the British.

The British fell on the French at close range, and the whole battle turned into a melee of individual ship duels. Captains fell back on their own initiative- something that commanders of ships of the line were absolutely forbidden to use in previous battles. As the British closed in, they delivered heavy raking shots down the French line, damaging several ships. At close range, the British gunners could not miss, and it became a contest of seamanship as ship captains attempted to close and hold the enemy in the smoke, or come alongside a friendly ship in need. The competence of the British captains and officers proved much higher than their French counterparts, and the individual duels came to favor the British. Battered, French ships tried to escape, and, too battered to pursue, the British let many get away. However, in the end, the French surrendered 6 of their 25 ships, and lost another sunk, while the English lost no ships at all.

The remains of the French fleet limped for home, while Howe and the British attempted to refit at sea. However, lost in the excitement of the battle and the victory over the French fleet, Howe lost track of the whole point of the affair- the French grain convoy. It reached French ports all along the Bay of Biscay on June 12th, while Howe and Vilaret chased each other around once reinforcements from both sides arrived. The British, by virtue of their capture of six ships with no losses, claimed a massive victory. The French worried less about who won the sea battle, and settled in to a big festival to celebrate the arrival of much needed food from the Americas, and the Committee solidified its control over France. The food would also fuel a massive offensive in fall, once distributed to the army.

While the British publically celebrated the victory over the French, internally, the Royal Navy fell into recriminations over the myriad failures of the battle. Most observers realized that, if the French had been remotely capable, the whole thing would have been a disaster. Many captains who were slow to turn into the fight found themselves rather out of a job, and with no chance of promotion. The British also began revising their communication procedures to ensure that everyone could get messages in such a close battle. This, they hoped would make these sorts of line cutting attacks more effective. But, in the end, it would come down to captains- and, after the Glorious First, admirals began looking for the sort of high initiative, skillful captains and junior admirals who could carry these attacks, as well as training their men for the sort of close action that demanded rapid firing and skill at boarding over all else.