Well, yesterday wasn’t the best day ever, so, perhaps we can distract ourselves with a little history. Also, I apologize for not publishing something last week- real life had to real life. This week, I think we should go back to the beginning of the era we’ve been discussing, to the development of the tercio system. As you know from our previous discussions, the tercio dominated the 1500s and 1600s. The Hapsburgs used the tercio to fight and win battles and sieges in the era, and most tactical innovation in the era focused on creating forces that could specifically beat the tercio. But, where did the tercio come from? For this, we have to travel back to the early 1500s, to the Italian Wars and the battle of Pavia. But, first, let’s talk a little about the army that the tercio was designed to defeat: the French Ordonnance army.

The French Ordonnance Reform Army

In the 1400s, of course, the French were trying to win the Hundred Years War against the English. If you remember back to our discussion of Agincourt, you’ll also remember that the French had a hard time facing the English in battle, but, in the end, won the war. They accomplished this by establishing a series of reforms, or ordonnances, that changed the relationship between the king and the army. The ordonnances created, for the first time in Europe since the Roman Empire, a standing army. Rather than relying on feudal relationships or mercenary contracts, the King hired his soldiers for fixed periods, usually a year or more, and provided money to maintain the army even in peacetime. This created a body of, effectively, professional soldiers in the service of the King of France, which gave as much of an advantage as any other part of the tactical system.

The main striking arm of the Ordonnance army was the Gendarme. The Gendarmes, in the 1400 and 1500s, were very heavy cavalry. They wore heavy plate armor- heavy enough to defeat longbows and any practical crossbow. Their horses also wore heavy armor to protect them. The men carried long lances, to duel with pike formations or to deliver a devastating charge against enemy horse, swords and other weapons as needed, such as picks or hammers to defeat armor. In fact, if you closed your eyes and tried to imagine a knight, you would probably imagine a Gendarme, rather than a knight. However, for the most part, they used the lance as their primary weapon. Lances allowed them to deliver a devastating blow against horsemen or infantrymen, and gave them the reach to deal with all but the tightest pike formations. The Gendarmes themselves charged in tight formations, the horses pressed shoulder to shoulder, and in two or three ranks. Few forces could expect to stand to such a charge.

The Ordonnance also created infantry forces of pike blocks supported by crossbows. However, the French infantry was never all that good, and, after the Hundred Years War, the Kings of France were rolling in cash. So, why pay for second best when you can pay for the best? The best, in the 1400s, were the Swiss pikes. The Swiss used pikes of about 15 feet in length, standing in tight formations, like any other pike formations. They also were supported by crossbowmen and halberdiers, who could attack and fight with other pike blocks, while retreating into or behind the pikes in case of attack by enemy horse. What made the Swiss different was their tendency to attack in deep columns, their discipline in formation, which made them hard to break, and their speed in the attack. The speed of their attack, ferocious discipline, and deep formations made them very effective in breaking up enemy pike formations, and either cutting through them on their own, or opening them up to an effective cavalry charge- like, say, from a formation of Gendarmes!

Another important fact about the Swiss- once bought, they stayed bought. And, once bought, they fought to the death. This is not always true of mercenaries.

The French also included in their forces a number of cannon, but these were usually used only at the start of battle, and moved rather slowly in the march. As a result, they often were not present at a battle, since French commanders usually did not want to wait for the cannon to arrive and deploy before entering a fight. When present, they were usually used for an opening fusillade or bombardment before the attack. Field cannon were still slow to reload in the 1400s, and so could not be used for sustained bombardment in the field in this era.

All together, the French Army brought the very effective Swiss pikes together with the very effective French Gendarme cavalry. This was an aggressive army, that sought to make a fast attack. The Gendarmes would form up on the flanks, with the infantry in the center. The Gendarmes would sweep the enemy cavalry from the field while the Swiss broke apart the enemy infantry at the center. As the enemy infantry collapsed, the Gendarmes would reform, and charge into the disorganized flank of the enemy. Game, set, match, France.

The Italian Wars.

Throughout most of the Middle Ages, the Italian peninsula could be divided into three parts: the Kingdom(s) of Naples and Sicily in the south, the Papal States in the center, and the northern principalities and republics. The northern states were small, but had become quite wealthy during and after the Crusades, as they became the middlemen between the Silk and Spice Road in the Levant and the rest of Europe. This wealth led, in turn, to the Renaissance, and, during the late 1300s and early 1400s, increasing autonomy for these states- remember that, historically, they were part of the Holy Roman Empire, though their wealth made them difficult to hold as the Middle Ages moved forward.

These smaller states engaged in a number of rivalries and wars with each other, even when they were more than theoretically part of the Holy Roman Empire. These conflicts continued throughout the 1400s. However, the nature of these wars changed in the late 1400s, when the larger powers- France, Spain and the Holy Roman Empire, were drawn into these conflicts on various sides, leading to a great power war for dominance in the Italian peninsula.

What drew and kept France and Spain in the Italian peninsula for most of the early 1500s were the kingdoms of Naples and Sicily. These kingdoms had changed hands many, many times throughout the Middle Ages, including stints under Muslim occupation, Byzantine control, and Norman control. However, by the end of the Middle Ages, the House of Trastamara, who ruled in Castile and Aragon, came control the area. In 1458, King Alfonso V of Aragon left Naples to his bastard son. However, the Kings of France held a claim on the throne from before the Aragonese takeover, which they couldn’t prevent because of the Hundred Years War. Meanwhile, the various parts of the House of Trastamra got their act together, and unified the various small kingdoms in Iberia into a more unified kingdom, commonly called Spain. (Technically, Spain isn’t a single kingdom until after the War of Spanish Succession, but.) So, we’ve got the stage set for a war against Spain and France, if the French ever had a reason to push to reclaim the Kingdom of Naples.

In 1494, Ludovico Sforza, the Duke of Milan, was in the middle of an on again, off again, war with his neighbor, the Republic of Venice. Sforza needed help in this war, and turned to one of his steadier allies, Charles VIII, King of France. Sforza encouraged Charles to pursue his claim to Naples, and, since his army was going to be in Italy anyway, maybe Charles could knock Venice around a little bit, too. So, in 1494, Charles brought his very powerful army into Italy, and began marching around. He faced little resistance- the Italians had money, but not King of France money. They couldn’t afford the best mercenaries, so they hired the sort of mercenaries that tend to give mercenaries a bad name. Rather than fight the French, everyone just got out of Charles’ way on his march south. In February, 1495, his army stormed Naples, and engaged in a particularly brutal sack of the city. The French drove the Trastamara king into exile, and Charles declared himself King of Naples.

The brutality of Charles’ troops, and the weakness of the northern Italian states, causes a rapid reshuffling in March of 1495. Milan and Venice got over their issues, and roped in Florence and Mantua. However, this wouldn’t be enough, really. These Italian states needed their own big friend to deal with the French, and so called upon the Kingdom of Spain, who had an interest in Naples, and the Holy Roman Emperor, their theoretical overlords. However, Spain and the Holy Roman Empire weren’t ready for war, so, as Charles headed back to France in 1495, the Italians massed their armies at the town of Fornovo, to try and beat Charles. However, Charles met the Italian soldiers outside Fornovo, brushed them aside and went home, proving, once again, the skill and strength of French arms. Beating the French army was going to take some work.

However, with the bulk of the French army back in France, Ferdinand, the King of Naples, could go on the counterattack. He asked the Spanish for help, but the Spanish could really only get one solder to him quickly- Gonzalo Fernandez de Cordoba, and that soldier would make all the difference. Cordoba led the forces of Naples against the French government, and crushed the local garrisons in late 1495. He then began preparing for the French response- after all, Charles’ big, bad army had to come back at some point.

Meanwhile, the Italian alliance began to fall apart, over the issue of Pisa. Tensions between Florence and Pisa threatened to blow apart the anti-French alliance, so Sforza asked the Holy Roman Empire to step in and settle the war. Maximillian I marched on south, and got involved in local politics in 1496. Charles stayed in France, reorganizing his army for another Italian expedition. However, in 1498, Charles was on his way to watch a tennis match when he tripped and fell, hitting a stone doorframe with his head. He died a few days later, having never regained consciousness. Charles had no sons or brothers, so the throne passed to his cousin, Louis, Duke of Orleans, who became Louis XII. This event would have profound implications for France in the 1500s, marking the second time tennis caused a dynastic crisis in France.

To solidify his claim to the throne, Louis decided to renew French ambitions in Italy. In 1499, the Florentines left the anti-French alliance, and asked for French help in the Pisan War. Louis also, himself, had a claim on the Duchy of Milan, and so decided that, while he was helping his Florentine Allies, he would take Milan for himself. His army easily smashed Milanese forces, taking the Duchy for himself without a siege. He then turned to Pisa in 1500, but failed to take the city, leaving a lot of enemies in the north, and a rebellion in the south. In an effort to end the Spanish supported rebellion in Naples, Louis agreed to partition Naples with the Spanish. However, neither the Spanish, under Cordoba, or the French under the Duke of Nemours, really intended to keep to the treaty. Open war broke out in 1503.

The Duke of Nemours had sizeable French forces at his disposal, including 650 Gendarmes, 7000 pikemen (about half Swiss) and 1,100 light horse. His army was larger than Cordoba’s, and more powerful. Cordoba had no real heavy horse. What he did have, though, was 3,000 landsknechts. These were German mercenary infantry, with a reputation almost as good as the Swiss. The landsknechts had a great deal of experience fighting in central Europe. While fighting there in the mid-1400s, they fought against the King of Hungary. In that fighting, the Hungarians used matchlock muskets to good effect against the landsknechts, and, never ones to turn away something that worked, the landsknechts began adding musketeers to their pike formations, but not in a particularly organized way.

To face the French, Cordoba organized his musketeers. He grouped them together for mass fire, and placed them along the flanks of his pikes. He drilled them in moving up to shoot, and then behind the pikes for defense. This should start to sound familiar.

Cordoba and Nemours finally came together outside of the town of Ceringnola in 1503. Cordoba drew up his forces on a hill, and dug a trench and rampart across his front. This was a pretty common tactic to use against the French and Swiss, and, usually, it didn’t really work. It would slow the attack, and break apart the formation somewhat, but the troops themselves were more than good enough to recover. However, Cordoba covered his trench with fire from his musketeers. The French opened the battle with two charges into the heart of the Spanish formation. When they hit the trench, they came under a heavy fire from the Spanish muskets, which broke the momentum of the charge, opened up the French formation and drove the French back. The French tried again, same result. The third time, they went around Gonzalo’s right- but to no avail. During this attack, however, the Duke of Nemours took a musket ball and fell, dead on the field. His second in command took charge of the Swiss, who attacked into the Spanish center. The Swiss managed to break into the Spanish formation, driving back the pikes. Cordoba deployed his muskets to the flanks of the Swiss columns, however, and their fire smashed the Swiss, driving them back. Cordoba ordered a general pursuit, eventually driving the French from Naples. Cordoba learned a valuable lesson about concentrated musket fire.

No one else did, though.

Also in 1503, Pope Alexander VI died, and Julius II won the election to replace him. Julius was Genoese, and rather concerned about the rise of Venetian ambitions in central Italy. Louis XII worried that Venice would come after his lands in Milan. Emperor Maximillian wasn’t thrilled with Venice, either In 1508, Julius brought the Papacy, France, Spain, and the Holy Roman Empire into the League of Cambrai to deal with the Venetians. The League did well in 1509, but, in 1510, the French decided Julius was going just too far, and switched sides to fight Julius. The Pope, no fool, hired his own Swiss troops, and cracked the whip against the Holy Roman Empire and Spain to get them to actually bring troops in to the war. He also convince Venice to switch sides.

The Spanish sent plenty of soldiers, but there was one they didn’t send- Cordoba. Needless to say, this lead to the defeat of the Spanish army at the hands of the French at the Battle of Ravenna. The Pope also suffered several reverses at the hands of the French, but, eventually turned things around enough in 1512 to restore the Sforzas to the Duchy of Milan. However, after taking Milan, Venice swapped sides again, allying with France. The Papal Alliance kept winning, though- until Julius died in 1513, leaving the whole anti-French group in disarray. Louis also died in 1515 in a freak jousting accident, leaving the throne to his nephew, who became Francis I. Francis continued the war against the weakened League, and smashed the Papal army at Marangino, reclaiming Milan. In 1516, the Papacy, HRE and Spain agreed to let Venice and France split northern Italy between the two of them.

With the rather decisive defeat of Spanish forces, Spain and the Holy Roman Empire went looking for answers. They found Cordoba, and his success against the French and the Turks in the early 1500s. He, and his second in command at Cerignola, Prospero Colonna, began refining the tactics they used at Cerignola, mixing muskets and pikes together. They taught these new tactics around Spain and the Holy Roman Empire, and more and more generals began adopting them in the peaceful years of 1516-1521.

In 1519, Maximillian died. The Empire passed to his grandson, Charles. Charles’ father had, by a very strategic marriage, taken the thrones of Spain and Burgundy. Charles, then, was King of Spain, Naples, Duke of Burgundy and the Netherlands, and, now Holy Roman Emperor. (He also owned about half of the Western Hemisphere, to boot.) Francis didn’t care much for this business, and decided to go to war against Charles. He invaded northern Spain (poorly) and the Netherlands, more successfully. His attack into the Netherlands caused the English to ally with the Empire. France called on its old Italian ally, Venice, for support, which drew Pope Leo X into the war.

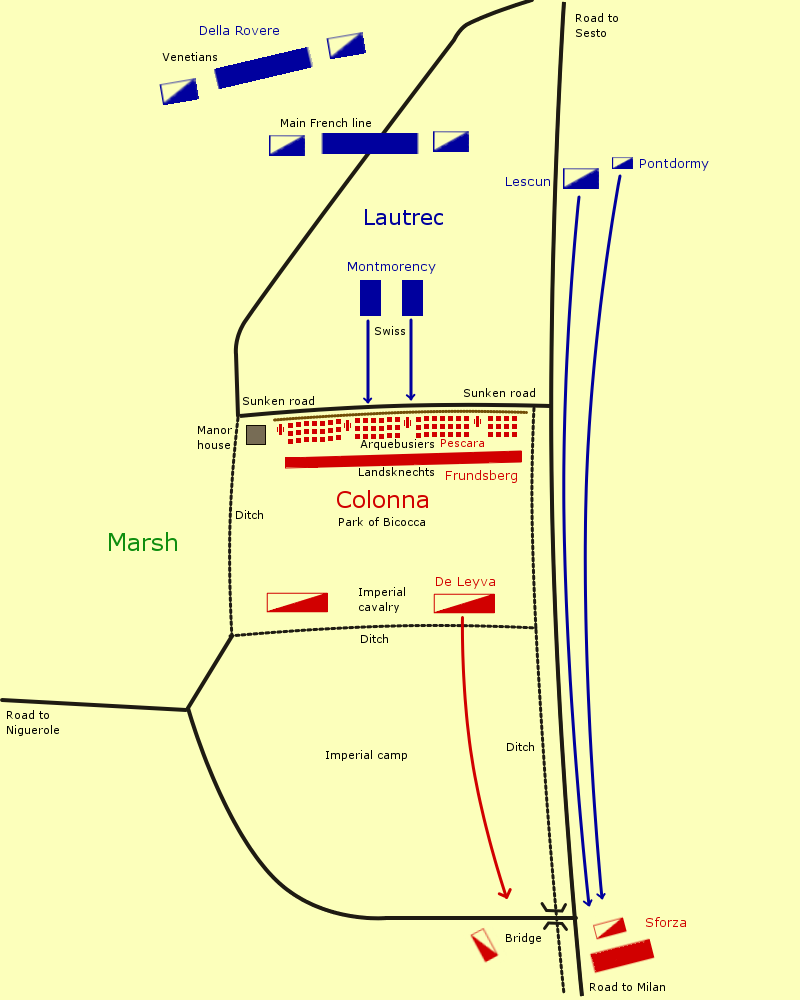

Charles’ forces in Italy were under the command of Prospero Colonna, Cordoba’s student. Francis gave command in Italy to the Vicomte of Lautrec, who hired a pile of Swiss pikemen to help him out. Colonna marched into Milan, driving the French back and restoring the Sforzas, again, to Milan. Lautrec got together even more men, raising the size of his army to 30,000 men, against Colonna’s 19,000. Colonna drew up his army in the fields of the manor of Bicocca in May of 1522, and dug in to await the French attack. Lautrec ordered the Swiss to attack the fortifications, while he led a force to Colonna’s rear to capture a bridge and cut his retreat.

Colonna, like Cordoba, massed his musketeers for a strong fire along his fortifications, backed by pikemen. He also brought up his artillery. The Lautrec had established his own artillery, but the Swiss attacked before they were in position. As the Swiss advanced, they came under heavy fire from Spanish artillery and muskets. When they reached Colonna’s rampart, they found it was taller than their pikes. Colonna’s muskets continued to fire down at the Swiss who made several attempts to climb the rampart. When the Swiss did make it to the top, the musketeers retreated, and Colonna’s pike attacked, driving them back. Eventually, the Swiss had enough, and called it a day. The rest of the French army retreated in good order, but the defeat pushed France out of Italy.

1523 was a bad year for the French. An English army approached Paris, the Duke of Bourbon rebelled, and the Spanish attacked Bayonne successfully. However, a split developed in the Imperial-English alliance, allowing Francis to take action. He got Scotland into the war, and he rallied his army, assembling 40,000 men, including 5,000 or so Gendarmes. This force drove into Bourbon territory in 1524, smashing the rebellion. Francis carried his army into Italy, where the Imperials and Spanish lacked the men to fight him, and retreated. Francis moved on the city of Pavia, which he began to besiege over the course of the fall and winter of 1524. Meanwhile, the Imperials were reinforced out of Germany, bolstering their numbers. Charles de Lannoy, the Imperial commander and student of Cordoba and Colonna, moved to break the siege of Pavia in February, 1525.

The French forces had established themselves outside the city, in the Park of Mirabella. This Park was fortified, giving the French fortifications to their rear as they faced the city. Lannoy sent his forces along this wall to the north to breach the wall, with another attack coming through the woods to the west of Francis’ forces. He also arranged for the garrison of Pavia to sally during the attack, catching Francis all around. Lannoy moved out in the night of 23-24 of February, hoping to catch Francis unawares and allowing him to breach the wall to the Park without resistance. This was successful, and Francis had to scramble to redeploy his troops.

Francis mounted his horse, and went to the head of the Gendarmes. He attacked the Imperial force coming out of the woods to the west, and drove them off with the weight of his charge. Meanwhile, his infantry formed up, and began attacking the Imperial army at the breach in the wall. However, as the French infantry moved in, they came under fire from Imperial musketeers. The French lacked any such force, and could not return fire. As their pike closed with the Imperials, French formations began to break up from the pressure of Imperial fire. When they tried to attack the muskets, the Imperial musketmen retreated, and Imperial pikemen attacked the French. Unable to overcome this agile combination of fire and melee, the French broke.

Seeing his infantry falling apart, Francis moved to reinforce with his gendarmes. However, the fire from Imperial muskets slowed the attack. As Francis rallied his men, reinforcements came to the Imperials, allowing them to deploy muskets along the flanks of the next French attack. This fire broke the attack, and the gendarmes. The Imperial infantry launched a counterattack, wading into the remains of the gendarmes, many of whom were dismounted from the fire.

Among the dismounted was Francis himself, along with many of his high nobles. Surrounded, he surrendered to Imperial forces, along with many of his gendarmes and nobles.

Francis’ capture ended French participation in this iteration of the Italian Wars. The Imperials held him prisoner, and began setting up terms for carving up large portions of France. However, fearful of Imperial strength, the Pope formed the League of Cognac, and France allied with the Ottoman Empire, to bring, pressure to bear on the Empire. However, these new alignments could not fight the new Imperial/Spanish Tercios, and the Empire rode them to victory in Italy in 1530. This didn’t end the wars of the 1500s, of course, but the next time war erupted, everyone in Europe would be either using tercio style tactics, or would be the Ottoman Empire. But, that’s a story for another time.