Ready to learn and learn fast.

Ready to learn and learn fast.Since the spread to run's rise a decade ago, the biggest evolution in that time is likely not schematic changes to that offense's base concepts, but rather the rise of running that offense through the no-huddle. Indeed, while the iconic spread teams may differ in the their base plays, they almost all employ no-huddle. Now that Ohio State's new offensive coordinator Tom Herman has made clear that Ohio State will join the ranks of no-huddle, up tempo offenses, it is worth examining why and how colleges run no-huddle.

An offensive staff goes no huddle to establish and control tempo. As offensive gurus like Homer Smith and Bill Walsh have long made clear, the offense and defense have certain advantages established bythe game's rules. While the defense always has an arithmetic advantage, the offense establishes the formation and numbers the defense must match, and controls when the play begins. The offense therefore gains an advantage when it controls and alters that tempo.

Last week I discussed altering tempo post-snap, but the offense can also alter tempo pre-snap. Enter the no-huddle. The no-huddle not only forces the defense to match tempo; for most spread teams it forces a defense to play at the offense's chosen tempo--namely fast. Coaches like Chip Kelly and Gus Malzahn's primary objective is to keep their offense relatively simple so that they can play at breakneck speed. Malzahn, for instance, wants his offense to run 80 plays per game. Their goal is to limit a defense's substitution, tire the on-field players, and eventually overwhelm the defense's capacity to adjust.

But the no-huddle is also effective for varying tempo. As Brophy discusses, the second signal teams will provide from the sideline (after whether to huddle) is the tempo. Generally, teams will go with one of two tempos. As Brophy discusses in detailing Charlie McFarland's system, the first is an up-tempo with the goal to snap the ball within five seconds of the spot.

Able is ISU's simple, no-huddle, first-sound tempo. No plays will be checked and all plays will be snapped on the first sound in the cadence.

The players will race to the ball spot, see the "Able" tempo in use, get set and receive the play call. The quarterback gives the play call twice "44.....44" (inside zone to the right) and the line will put their hand in the ground ready to play ball. The quarterback initiates the cadence, "Set.....Hit!", the ball is snapped, and the players race to the next ball spot and repeat the (sideline signal) procedure.

The second tempo (McFarland calls it "Baker") is where the offense will get to the line with a play call as above and then do a hard count cadence, but the players will then look to the sideline for the coaches check based on the defense. By this point, all college football fans are familiar with this hurry to the line and then check the sideline approach. As Brophy describes:

Rather simply, everything is the same as "ABLE" speed with the exception that the offense will review with the sideline/Offensive Coordinator before continuing the snap cadence (this is Blake Anderson's "OC" tempo). The coordinator now has the option to change the original play call or 'green light' the first call (and execute the original call).As an example, the pre-snap to snap audible would sound like;

The specialists would then look to the sideline (tight end would stand up out of stance and look to sideline). From here, the play can be checked (based on alignment, pre-snap look presented by the defense) or the original play ("indy girl") can be continued. If the former, the play would be called out and repeated by the quarterback and he would go through the cadence. If the latter, he would declare a "green" call ("green, green") and go through the cadence (running the original play called).

"Right – right – baker –baker" [ formation + tempo] called by quarterback

"8 man 8 man" [front ID] called by center

"indy girl – indy girl " [play call (iso lead to the right) ] called by quarterback

"set..... hit!" [cadence]

How is it Executed?

Now that we see the why, how is such an attack implemented? Brophy has a great rundown here, but I will try and distil his discussion down to its basics.

An offense will generally have four individuals providing signals. Here is Brophy's description.

The sideline will provide the information in this sequence:

Huddle / no huddle

The following will detail the process in which they operate this tempo. Once the ball has been whistled dead, the offensive line rushes to get set at the new ball spot. The specialists, particularly the tight end / fullback, will look to the sideline to see what personnel grouping will be included in the upcoming play. This will determine if they remain in the game, or if their particular personnel grouping dictates that they come off the field on this play. With the appropriate players in the game, the formation and motion will be signaled in. Players keep their eyes on the first signal caller (and disregard the others) until the given formation is set. Once set, the specialists will look to get the play call. Only the specialists know the play signals, the linemen only know the tempo calls (and rely on the audible call of the quarterback for the play call).

Tempo: Able/Baker/Charlie

Motion & Formation

Play Call

An offense must develop a language that both delivers this information in decipherable chunks, yet does not give information to the defense. Generally, an offense will do this with both a) a signaler and b) the play boards (that Oregon has made so infamous).

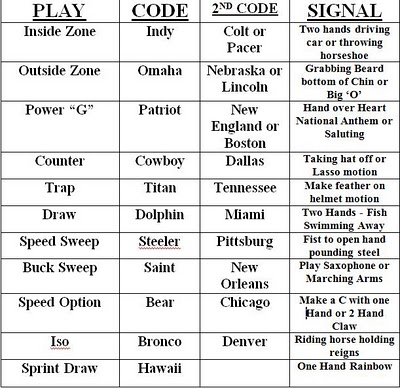

Once the formation and motion is delivered, the players will next look for a color code. The color indicates whether the board or signaler is 'hot.' The signaler is in turn tasked with run or play-action pass plays, while the board contains passing routes. The play types are generally grouped together in a common theme to help with recognition. As Brophy states, for example, runs can be coded by NFL teams, passes by college teams, etc.

For pass plays, once the board is hot, the offensive line will note the dummy call and have the pass protection delivered. The specialists, meanwhile, will look to the board. The board can either associate pass concepts by a symbol (such as Oregon), or a number tree. The board's quadrants will represent primary and secondary receiver routes. During this entire process, the Quarterback can watch the sideline and audibly deliver the information to the other offensive players. In this way, a team can effectively run a no-huddle offense with efficient coordination, with the goal to force the defense to match and respond to the offense's tempo.