Imagine crossing the finish line of a marathon. You’ve trained for months, maybe years. You’ve made it to your race day despite the numerous challenges that accompany such rigorous preparation. You’ve pushed your body to its limits, and you’ve finally accomplished your goal. What an incredible feeling.

Now imagine the race officials telling you that you’ve done something wrong. You took a wrong turn somewhere on the course which caused your time chip to malfunction. Your time cannot be recorded. In fact, you can’t even be considered a true finisher... that is, unless you opt to start all over. At mile zero.

Ohio State defensive lineman Dylan Thompson can likely relate. The 6-foot-5, 275-pound freshman was one of the nation’s top recruits joining the program this past season. He had 17 quarterback sacks as a high school senior to garnish a most impressive prep career.

He dedicated the immeasurable hard work necessary to play at the NCAA Division I level, and he was ready to contribute as a Buckeye. Marathon one. Then, in August, he fractured his left kneecap in practice. Prescription: Three months of rest. Start over.

Thompson, on the heels of the injury, was forced to redshirt his freshman year in Columbus. He opted against a surgical repair, which was a perfectly reasonable decision that’s met through open communication between the athlete and his healthcare providers weighing the risks and benefits of treatment options.

He took the prescribed rest. He supported his teammates from the sidelines as they moved through a stellar season towards the first ever College Football Playoffs. He was exceptionally patient, and finally he made his way back into practice. Marathon two completed.

Enter December. Thompson re-fractured his kneecap during practice. Start over. This time, the fracture required surgical intervention. He had the operation in early January.

Kneecap (patellar) fractures are most often caused by direct trauma to the knee. This can happen with a fall or by a hit to the knee (especially by a helmet), because the kneecap is so exposed near the surface of the skin.

This injury can be excruciatingly painful. The kneecap is attached to the quad muscles, so every time the quad muscles are activated, they tug and pull on the broken bone. Quads aren’t just used for squats and leg presses. These muscles contract with every step. The pain of trying to walk after a patellar fracture could be seen after Kyrie Irving’s recent injury during the NBA playoffs.

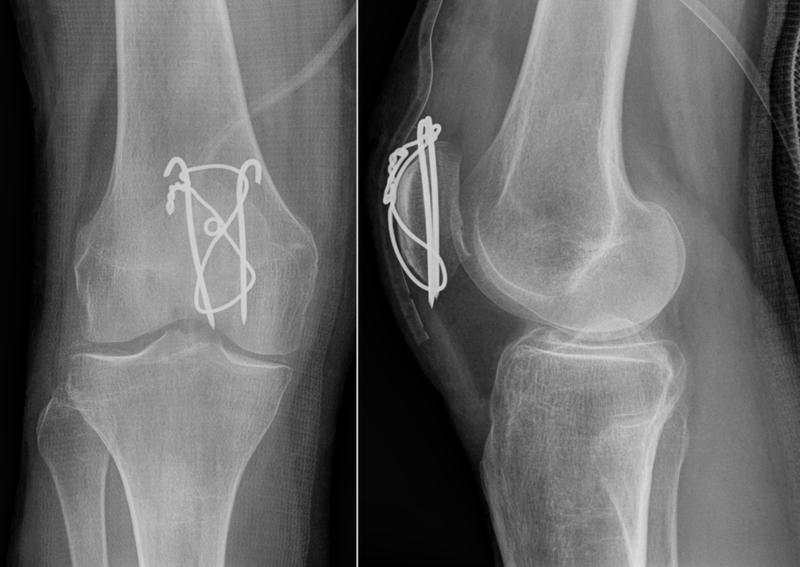

If a kneecap fracture is displaced, meaning the pieces of broken bone don’t line up well with each other, surgery is done to puzzle the bone fragments back together. Pins, tension bands, and/or wires hold the newly approximated pieces in place while the bone heals back to its normal shape and position.

After a period of rest and immobilization, rehab is used to strengthen the supporting muscles of the knee joint and restore range of motion. Weight-bearing exercises are gradually incorporated, and patients can return to full activity after medical clearance.

For his first year as a college athlete, Dylan Thompson has had more than his share of setbacks. Nonetheless, he has persevered. He turned all the way around to the starting line – two times. He overcame a discouraging diagnosis twice, and because of these obstacles, he enters the upcoming season as a resilient veteran in the realms of physical and mental stamina. We are thrilled to watch how he channels this fortitude, and we will be cheering him on for what we hope to be a healthy four-year career as a Buckeye.

References: