Gene Smith has been under scrutiny for 18 months.

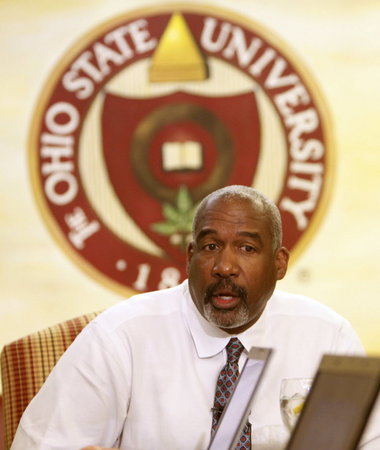

Gene Smith has been under scrutiny for 18 months. We spoke with Ohio State Athletic Director Gene Smith last week about the turmoil of the previous 18 months, facing adversity, and the state of the department both on the field and in the classroom.

It has been nearly 18 months since the first sign of distress inside the Ohio State football program. What transpired over the next year and a half – the removal of a legendary coach, the star quarterback unceremoniously leaving school, suspensions of key players, a bowl ban and enough bad publicity to fill the Library of Congress – is enough to take down the biggest of organizations, let alone a college football program.

In May, JPMorgan Chase reported a breathtaking loss of at least $2 billion in trades, the last thing a slumping and jittery world economy needed. The news came as a shock to many in the financial sector. After all, JPMorgan was viewed as the top bank in the United States captained by one of the best CEOs in the world in Jamie Dimon. Dimon even has the plaque to prove it. In 2011, Institutional Investor named him CEO of the Year.

Dimon characterized the strategy that led to the billions in losses, which dealt with the risky practice of betting on derivatives, as “flawed, complex, poorly reviewed, poorly executed, and poorly monitored.” For a company with $2 trillion in assets, this is hardly the beginning of Chase's demise, but it's a black eye that will accompany Dimon and the bank for many years to come.

In March 2011, in a hastily called press conference, Ohio State reported that its head football coach knowingly failed to notify his superiors about information he received concerning allegations of improper benefits involving two high-profile players. The revelations stunned the sports world. Jim Tressel promoted an image of integrity and accountability and athletics director Gene Smith, once considered a candidate for the top spot at the NCAA, had never dealt with major violations at Ohio State.

After Tressel’s resignation on Memorial Day, Smith characterized Ohio State’s problems as “not systemic” and “the work of one individual.” The 2011 football season didn’t ease the angst surrounding the program. The Buckeyes stumbled through their first losing season in 23 years and more violations made headlines throughout the season. Then, in December, the NCAA slapped a one-year bowl ban on Ohio State.

For a school that can call upon a successful son of Ohio to come home and lead the program, the setback looks to be a speedbump, but Smith will have to live with the ordeal forever linked to his own biography.

Much has been written by the local and national media about the past year and a half inside the athletics department at Ohio State. Very little of it has been of the positive variety. Scandal has that ability – like a car crash – to keep eyes and ears attached to the scene. While the football program’s mess garnered much of the attention, the 35 other varsity sports delivered arguably the best performance ever in an academic year. The Buckeyes finished second in the Directors’ Cup standings for the 2010-11 seasons and are locked into fourth-place in the current year’s standings.

The men's volleyball team won the 2011 national title.

The men's volleyball team won the 2011 national title.“It was a great year,” Smith told Eleven Warriors last week in an interview in his office. “It was so hard as we went through the scandal not to be able to promote the great success that our student-athletes achieved. We’d never finished second in the Directors’ Cup. It was a great accomplishment and achievement that our department wanted to celebrate. We did internally, but it was hard to really focus on that externally.”

Among the successes were national championships won by the men’s volleyball and fencing programs and the men’s basketball team’s berth in the Final Four.

“It was a great year on all measures – the conference championships, national championships,” Smith said. “We had 14 coaches win coach of the year honors. The volleyball team won the national championship, and it got some attention, but it wasn’t what it should have received. And it was their first, so you really wanted to keep that going for the kids so we had to be creative a little bit. It was unreal the success our kids had last year. The Olympic sports, anytime they accomplish something that great, we try and find a way to celebrate those moments.”

One of those moments came June 9 at the Ohio State Football Women’s Clinic. During the clinic, word spread that women’s track athlete Christina Manning won the national championship in the 100-meter hurdles. Suddenly, more than 700 women, almost all of whom had no idea who Manning was, were hooting and hollering because of her accomplishment.

“It was an amazing scene,” Smith said. “Manning is just the second female ever in our great history of women’s track to win the national title, so you want to find a way to celebrate it. Buckeyes have pride in the accomplishments of their student-athletes. Anytime any of those sports or student-athletes accomplish something, you want to pause and celebrate it because what they put into their sport is the same football and basketball players put in. It’s a lot of hard work and effort to have a chance to compete at the highest level.”

The good news wasn't limited to the playing fields, however. A school-record 548 student-athletes earned the scholar-athlete distinction this year. That goes along with 312 academic All-Big Ten honorees – the most in the conference.

This past week Ohio State’s football team was one of 11 Football Bowl Subdivision teams recognized as an Academic Progress Rate overachiever. Ironically, the University of Miami, also in hot water this past year in regards to NCAA rule breaking, joined the Buckeyes on the overachiever list.

“These teams prove that it is possible to not only balance academic and athletic commitment, as most student-athletes do; but to exceed standards and post outstanding academic scores,” NCAA President Mark Emmert said. “The drive and determination shown in the classroom and on the field by these men and women represent what it means to be an NCAA student-athlete.”

Five national championship teams from 2011 were recognized, among them the Ohio State men’s volleyball team.

“Each of Ohio State’s 36 teams continued to improve its Academic Performance Rates over the most recent four-year average (2010-11),” Ohio State Professor John P. Bruno, Ohio State faculty athletics representative, said in a statement. “This indicates our student-athletes are successfully completing the academic benchmarks associated with eligibility to compete. Moreover, five of our teams have distinguished themselves as being recently recognized by the NCAA as having APR scores in the Top 10 percent of their sports on a national level. The sports are football (within the FBS cohort), men’s and women’s tennis, and men's and women’s volleyball. This strong performance speaks to the commitment of our student-athletes to their academic progress and to the support they receive from coaches and our terrific academic support staff.”

When Smith arrived in Columbus in 2005, the student-athlete graduation rate was a paltry 62 percent. It has since risen to 81 percent, and of the 171 student-athletes who graduated in the 2011-12 academic year, over 92 percent left Ohio State with a job or went on to enroll in a master’s degree program – staggering numbers in the present floundering economy.

“The main thing we changed was how we worked with the individual student-athlete,” Smith said. “Instead of having group sessions or study halls, I required an individual academic plan. When a recruit signs with Ohio State, we get all the academic indicators, transcripts and test scores and figure out what your deficiency is. If it shows you are deficient in math performance, when you get to campus we make sure we have someone ready to work with you on that.

“We hired learning specialists and increased our tutors because I want the student-athletes to be as successful in the classroom as they are on the playing field and instill that competiveness. We built incentives for student-athletes who became 3.0s (the level to achieve scholar-athlete status). I remember we didn’t have many 3.0s in football when I first came, and that was a travesty. So we really started ratcheting up what it meant to be a 3.0. Now every student-athlete wants to be at that scholar-athlete banquet in May. We also work at the other end of the spectrum. If you’re a high achiever, how do we help you get a post-graduate scholarship? We have the largest number of post-graduate scholarships we’ve ever had – 13.”

Smith has also worked with Christine Poon, the Dean of the Fisher College of Business, to form a Dean’s Leadership Academy Cohort. Of the 144 student-athletes enrolled in the College of Business, 12 to 15 with a GPA of at least 3.3 and strong leadership traits will be admitted to the cohort.

Sitting in his office on a recent Tuesday, Smith gazed outside his 10th-floor window in the Fawcett Center across Olentangy River Road to the Woody Hayes Athletic Center. Mere months ago, a frown may have adorned Smith’s face when looking in the direction of the palatial football facility. Storm clouds may have also been seen on the horizon. But not on this splendid June day. Instead, Smith smiled as a deep blue, sunny sky offered a backdrop that could only be diminished by a sunset amid the San Gabriel Mountains at the foot of the Rose Bowl. It also offered a metaphor Smith had lived for more than a year: blue skies.

“As we were going through the scandal, there was a point in time when I realized all we had to do was get out the other side,” Smith said. “I said, ‘We have to get to blue sky.’ I knew once we got to blue skies we could begin to focus on building (the football program) back. The foundation was successful. We didn’t have a football program that was broken. We’re pretty doggone good.

“You look back at all the arrows that were shot at us, the reality is one single individual made a mistake along with some student-athletes. In the total scope, though, there were accusations against our program that were totally unfounded. So we also have to look back at the people who were attacking us and say, ‘Why?’ Why, because we were at the top of the pedestal. When you’re very successful and errors occur, the naysayers are going to jump on you. We never lost our focus. Every day we came to work, I said, ‘Do not let this distract us from our mission.’ That’s why we were successful in all the other areas.”

Criticism rained down on Smith for what fans exclaimed were a multitude of reasons, among them Tressel’s ouster, the amount of violations uncovered and for not self-imposing a bowl ban. Though there are plenty of fans who will go to their deathbed convinced Tressel forwarded the Cicero email to Smith and many more who believe he should have known a postseason ban was coming, Smith would argue that was not the case.

By the time Tressel resigned, a change was both imminent and necessary. No coach is bigger than the OSU football program, a lesson learned in 1978 when Woody Hayes was fired, and Tressel left the administration with no choice. Smith has never been tied to any of the wrongdoing that occurred in the memorabilia-for-tattoos scandal or the Bobby DiGeronimo fiasco that accused football players of being paid wages for hours they did not work. Ohio State fans and a large segment of the media believed the Buckeyes’ self-imposed scholarship reductions combined with their proactive approach with the NCAA would steer them clear of any postseason ban.

Eighteen months later, Ohio State football is the boy that fell in the mud puddle only to come out wearing new clothes.

“There are a few schools in the country that could overcome a scandal that lasted (as long as ours) and come out the other side and be in pretty good shape,” Smith said. “We were fortunate. We wanted to secure an outstanding leader to take over for the football program. That contributed to it, but also, because we have a great platform: we are strong academically, we have 500,000 living alums, and we are very cohesive; everyone has pride in the institution.”

So, what does one reflect on, living a year-long nightmare?

“You always have to keep it in perspective,” Smith said.

Just seventy-five days away from an Meyer's first game, Ohio State didn’t just weather the storm. They blew back with thunder and lightning of their own. Superior as an institution, healthier as an athletics department and stronger as a football program, Ohio State University appears better equipped than two years ago when it was in the midst of six consecutive Big Ten championships and six straight BCS games.

“We haven’t played a game yet,” Smith cautioned. “I don’t get caught up in the euphoria. You have to keep in mind that we have to get to the season and then see what we believe will happen. Then if it does happen, the euphoria will sustain itself. But what happens if there’s a bump in the road?

“But, yes, you are in a better place when you face adversity. This is what we teach our kids. You are better when you come out the other side. You’re better as an individual, better as a program, our policies and procedures are better. I don’t know if, ultimately, we’ll always have the ability to meet the expectations. I don’t think it’s realistic.”

Two days after Ohio State’s first loss to arch-rival Michigan in seven years, Meyer was hired as the Buckeyes’ head coach. Forty-eight hours was all the Wolverines had to savor a victory they’d waited what seemed like a lifetime to secure. Soon, Meyer hit the ground running and wrapped up a top-five recruiting class and there was no doubt about whether order had been restored in Columbus.

Like Chase, the Ohio State brand will rebound and endure. Dimon and Smith -- two polarizing, yet household names -- will relish getting to blue skies again.