Wide receivers aren't supposed to dominate the SEC.

But after leading the nation in catches and receiving yards, Amari Cooper more than made his mark this fall for the Crimson Tide. The junior from powerhouse high school program, Miami Northwestern was more than deserving of the SEC offensive player of the year award, as he re-wrote school and conference record books.

Even though Nick Saban and the Crimson Tide have produced elite NFL talent at the position before, no receiver has contributed so much to an Alabama offense in the illustrious history of the program. Not since Larry Fitzgerald in 2003 has a wideout been invited to the Heisman ceremony, showing the rarity of seeing someone at the position make such an impact on the national stage.

Cooper has caught 10 or more passes in five games, and eclipsed the 200-yard mark on three separate occasions this fall, showing remarkable consistency. These big numbers aren't by accident either, as he accounted for 45% of Alabama's receiving yards, the highest total of any player in Division-1. First-year offensive coordinator Lane Kiffin has made getting the ball to Cooper a priority, much the same way he did at USC two years ago when Marquise Lee put up very similar numbers.

As we look ahead to the Sugar Bowl on January 1st, it's clear that for the Buckeyes to beat the top-seeded Tide, they must slow down Cooper. Though they've faced a handful of talented receivers this fall, such as Tony Lippett of Michigan State and Leonte Caroo of Rutgers, Cooper presents a completely different challenge for the Ohio State secondary.

His unique blend of size and athleticism allows him to be a force in the screen game, where Kiffin calls countless variations to simply get him the ball in space. In the SEC title game against Missouri, Kiffin regularly packaged an inside run with a screen to Cooper, giving quarterback Blake Sims an easy way to beat the aggressive Tiger defense no matter their alignment. While Cooper may not be quite as dangerous an open field runner as Sammy Watkins was for Clemson a year ago, he's still plenty athletic enough to make multiple defenders miss.

The way Kiffin incorporates Cooper most into the game plan though is very much of an NFL style, often calling quick, three-step routes such as hitches, slants, and speed outs on first downs. While most receivers his size simply rely on their big frame to shield defenders from making plays on those routes, Cooper is an excellent route-runner. He consistently releases off the line the same fashion, as to not give his defender any hints, before exploding out of a cut to create separation.

In addition to short routes that get him the ball quickly, Kiffin and Sims regularly look for him in the play-action passing game. One of their favorite concepts is roll-out to the right off a faked outside zone handoff, looking for Cooper on a 10-12 yard comeback route.

Once the shorter routes have been established, the Tide attack cornerbacks with a myriad of double-moves, baiting defenders into a jumping a short route before taking off downfield. Here again Cooper shows his polished skills as a route-runner, making his opponent believe another hitch route is coming before breaking quickly downfield.

But double-moves aren't the only way Cooper attacks downfield. Much in the same manner the Buckeyes have found success matching up Devin Smith on safeties downfield, Kiffin looks to put Cooper in similar situations.

On his second of three touchdown catches against Auburn, Cooper releases directly toward one of the deep safeties, who are playing a Cover 2 zone. As his receiving counterpart DeAndrew White (#2) releases on a corner route to the opposite side, Cooper starts to bend his route to the outside before cutting back to a wide open middle of the field. The safety has little chance to stay on top of Cooper and bites on the outside move, leaving him all alone for an easy catch.

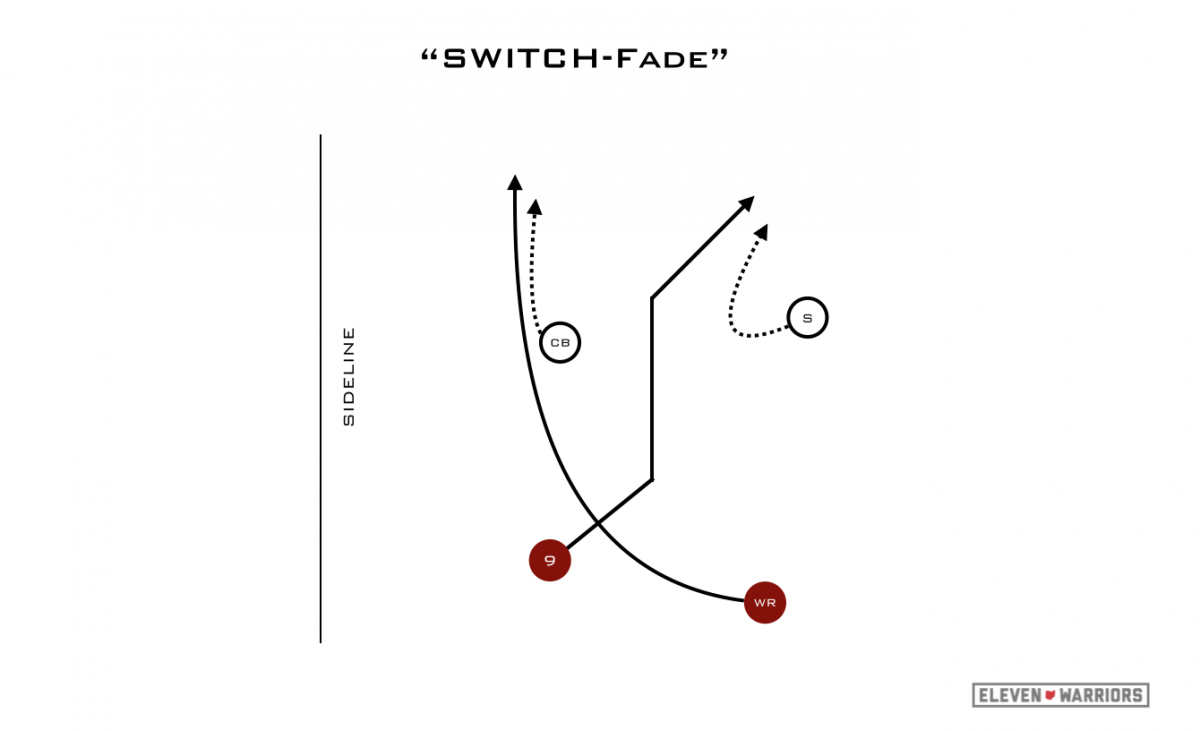

Against a defense that runs Cover 4 like the Buckeyes, Kiffin likes to run "switch" concepts that allow Cooper to line up as the outside receiver before breaking inside immediately after the snap. In this defensive scheme, the cornerback is responsible for the outside receiver while the safety takes the inside man, meaning he must account for Cooper by himself on the post route if they run the "switch-fade" concept.

When teams have tried to bump him off the line to disrupt his route and timing, Cooper hasn't been deterred. Not only is he strong enough to easily swat away the hands of his defenders, but he has now gotten his opponent off-balance and can create space even easier.

If there are any young receivers that are reading this, watch the way his helmet never moves in any direction until he makes his break. That's exactly how a five-yard dig should be run, regardless of the fact that he had to beat a defender in press coverage off the line.

In the red zone, these skills become even scarier for opponents, where Cooper has caught four touchdown passes, the most of anyone on the team. Not only is he able to easily create separation as we've seen, but his ability to track the ball in the air and catch with his hands makes him nearly unstoppable near the goal line on fade routes.

Cooper is truly a complete receiver, possessing all the tools to beat an opponent. He doesn't have any real weaknesses for an opposing coaching staff to exploit, other than an occasional lack of effort when run-blocking.

So as Ohio State prepares to face him in New Orleans, it's likely that they'll take an approach similar to the one Missouri took. While the Tigers play a slightly different base scheme of the "Tampa (Cover) 2", it's more about technique than scheme in this instance.

Knowing Cooper would run a number of short, quick routes that would be very difficult to stop on their own, they simply played off of him and ensured that the cornerback to his side maintained outside leverage. This defender always turned him back towards the middle of the field after the catch, where the rest of the Tiger defense was waiting to help make a tackle, including hustling defensive linemen.

The Tigers clearly made it a priority to know where he was lined up at all times, and if the ball went to his side, they hustled to corral him. Identifying him shouldn't be too difficult on each play, as the Crimson Tide don't substitute receivers that often, and rarely ever have more than three of them on the field at once.

From a schematic standpoint, they employed a great deal of "Man 2" defense, meaning the cornerbacks and linebackers played man-to-man coverage while the two safeties behind them played deep zones in each half of the field to help defend any deep passes. Whenever Alabama lines up with Cooper in the slot, I'd expect the Buckeyes to employ such a scheme, with Doran Grant likely taking the lead in coverage.

Though the Tigers ultimately lost the game, it wasn't because of Cooper, as even though he caught 12 passes, he only amassed 83 yards, with his biggest gain coming on a screen pass in which he broke a tackle before picking up 17 yards. Additionally, the Arkansas Razorbacks, whom Ash coached a year ago, also implemented this scheme earlier in the year and held Cooper to his season low in both receptions and yards.

However, Man 2 does leave the defense exposed to the running game, as many of the back seven defenders are focused elsewhere at the snap. Luckily, Missouri and the Buckeyes share a similar strength up front to account for this. The Tigers did a great job of getting penetration in the backfield on running plays as well as pressuring Sims and forcing him into bad throws.

Although Sims is a senior, he spent this first half of his career in Tuscaloosa playing running back, and his fundamentals can show it at times. When pass rushers get in his face, he'll often throw off his back foot or release the ball with a side-arm motion, both of which usually result in errant, incomplete passes.

Tiger defensive end Shane Ray was ejected early in the second quarter for a targeting penalty, which likely changed the game, as their best pass rusher (and probably best player overall) spent the majority of the game in the locker room. Up to that point though, the Missouri defense had forced three straight stops, keeping their offense in the game.

If the Buckeye defensive line can replicate their performance against Wisconsin, dominating in both phases and allowing the secondary to focus on containing Cooper, they'll have taken a big first step towards victory.