Today as I’m sure you all know, is the 75th anniversary of the last major air strikes of the Battle of Midway. The Battle has been covered before on 11W, by NavyBuckeye, whose post you can see here.

However, since we’re looking at the 75th anniversary, I thought it would be good to dig into the battle in some depth, as a way of remembering the struggle that ensued on the seas 75 years ago, and the men who made- and maybe changed- history.

The Opening Moves

The great Pacific War finally erupted, after much anticipation, on December 7th 1941, when the Japanese launched an attack from aircraft carriers against the main American fleet anchorage at Pearl Harbor. The reasons for this are controversial, but the short version is that the Japanese needed to seize control of the oil fields in the Dutch East Indies. However, the United States controlled the Philippines, which set astride the route through the South China Sea that the Japanese needed to control the movement of oil back to the Japanese islands. This meant that the Japanese needed to control the Philippines, and the largest obstacle to the easy conquest of the Philippines was the US Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor.

The sudden attack in Hawaii prevented any real American response to Japan’s next moves in the Pacific. A sudden offensive in the South China Sea led to the rapid conquest of the Philippines, the Dutch East Indies, Singapore, Malaya, and an entry into New Guinea. In the Central Pacific, the Japanese solidified their position by invading Wake Island and Guam, removing the American bases between Japan and their holdings throughout the Central Pacific.

Japan’s main strategic goal in all of this, other than establishing control over the oil supply it needed desperately, was to create a defense in depth across the Pacific to either the Philippines or the Japanese home islands. The Japanese planned to force the Americans to march along the island chains of the Pacific, fighting battles against the carriers and cruisers of the Japanese fleet. These battles would weaken American resolve and forces until they could be defeated in a massive, decisive battle on the shores of Japan or Manila. After that defeat, the Japanese would offer to negotiate peace on generous terms.

The Japanese, however, did not anticipate actually establishing their positions until mid 1942- and, so, when, by February, they had achieved most of their objectives, they were at something of a loss of what to do next. The Japanese decided to keep pushing forward, sending some forces into the Indian Ocean to raid British bases in India, while another force landed on New Guinea, pushing to the Owen Stanley Mountain Range.

The Americans didn’t sit on their heels for long, however. Early in 1942, the US carrier forces launched a series of raids and sweeps through the Central Pacific, attacking Japanese island bases and whatever ships they could find. However, these were expected, minor annoyances to the Japanese. However, one raid changed Japanese priorities quickly. On April 18th, 1942, a squadron of B-25 medium bombers took off from USS Hornet, who had snuck deep into Japanese waters. The B-25s attacked targets around Japan, including near the Imperial Palace in Tokyo. Fearing further attacks against the Home Islands, Japanese Admiral Isoruku Yamamoto decided to extend the perimeter held by Japanese forces to prevent further attacks. This required moving in three major directions- into the Aleutian Islands near Alaska, the capture of Midway Island, and a deep movement in the South Pacific, taking New Guinea, the Solomon Islands and New Caledonia.

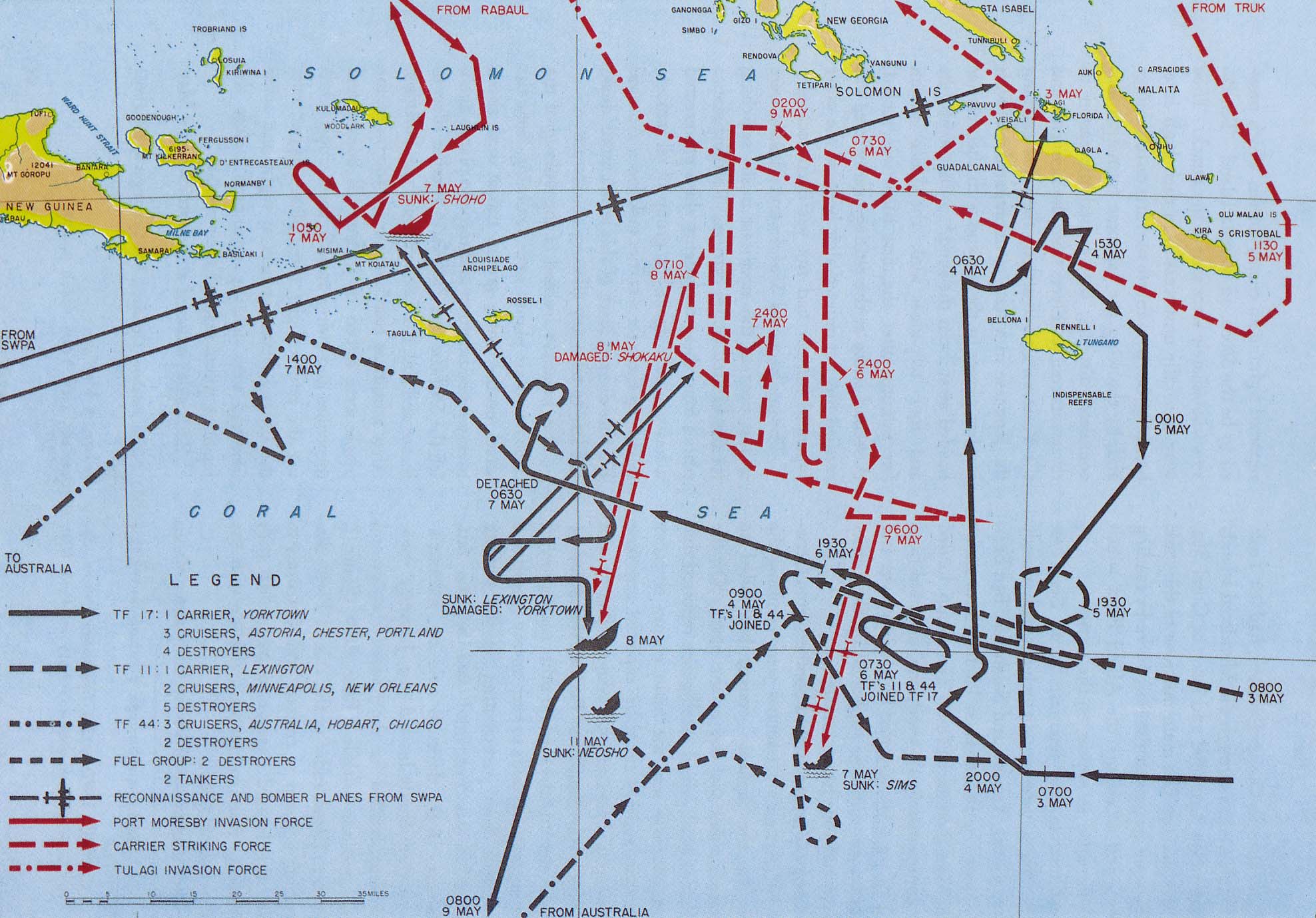

One major operation was already underway in the South Pacific to support this new plan. A pair of Japanese carriers, Shokaku and Zuikaku, sailed to support an amphibious attack across the Solomons and the Coral Sea to Port Morseby, the main Australian base on New Guinea. US intelligence, however, using broken Japanese codes, sent a carrier force to try and intercept this force. On May 7th and 8th, the Japanese carriers traded attacks with aircraft from USS Lexington and Yorktown. Over the course of the battle, the US ended up taking the worst of it- Lexington sank and Yorktown suffered extensive damage. However, Japanese aircraft losses were heavy, and their carriers also suffered serious damage. Without the striking power of the carriers, the Japanese invasion fleet turned back rather than face the land based air in Australia and Moresby.

Preparing for Midway

Even before the Port Moresby operation, Yamamoto was planning a massive operation to complete the perimeter in the North and Central Pacific, and also deliver the final blow to the US Navy at the same time. His plan was quite complex. First, a force of older battleships, light carriers and cruisers would attack Dutch Harbor, the main US base in the Aleutians. After that attack, they would move to assault the islands of Kiska and Attu, seizing them and preparing them for use as bases against US forces in the area. At the same time, the rest of the Japanese fleet would sail for Midway. The main carrier striking force, consisting of four fleet carriers, would attack and destroy the American airbase on the island, then followup with attacks against American defensive positions. With that done, another force would move in, take the island, and quickly repair the airbase to accept Japanese planes. When the American fleet scrambled to retake the islands, the Japanese would pin the American carriers between the land based air at Midway and the carriers and destroy them. Whatever was left, the Japanese battleships, which trailed behind the carrier force, would sweep in and destroy them in a massive gun battle. With the US Pacific Fleet effectively destroyed, either the US would sue for peace or the Japanese would be able to finish reinforcing their extended perimeter.

Of course, the Battle of the Coral Sea did throw a bit of a monkey wrench into this plan. With Shokaku and Zuikaku combat ineffective for the next several months, they couldn’t make the trip, However, Yamamoto knew that, when the Americans finally arrived, they would be much weaker, too. With Lexington sunk, Saratoga still being repaired from damage suffered in early 1942, and Yorktown effectively crippled at Coral Sea, he would only need to face two US Carriers- Enterprise and Hornet.

Admiral Chester Nimitz, commander of the US Pacific Theatre, had two aces up his sleeve, however. First, he still had, mostly, broken Japanese codes, and had plenty of warning that something was up. Even without the codes, his signals intelligence warned him of a major operation underway. His codebreakers figured out that the main target was Midway by a clever bit of subterfuge- they sent a false signal that Midway’s water purification plant had failed, which the Japanese radio stations that caught it sent up the chain, confirming Midway’s code designation. So, he knew the Japanese were coming, and that their target was Midway. They also had one more advantage- the yard hands of Pearl Harbor. They threw themselves into work on Yorktown, and, within 48 hours, had her capable of air operations and sailing to Midway. Of course, things weren’t quite perfect: Admiral Bill Halsey, the American carrier commander with the most experience, was sick with a skin disease, and couldn’t sail. While Jack Fletcher, the commander at Coral Sea, would be in overall command, the two strongest carriers would be under the command of Raymond Spruance, who had no experience in carrier operations.

There was only one possibility that Yamamoto’s planning team hadn’t wargamed, since they believed it too remote based on their assumptions: that three functioning American carriers would be northeast of Midway before the arrival of the Japanese forces. Of course, this was where Spruance placed his carriers in the days before the Japanese arrived in the area.

The Battle of Midway

The warning of coming action at Midway helped the Americans, in addition to moving carriers into place, beef up their defenses of the island. In particular, PBY Catalina flying boats allowed the US to have a well organized, deep, and extensive search pattern by air without using carrier or land based combat assets. This paid out on June 3rd, when they spotted the Midway Occupation Force, under Admiral Tanaka Razio, Later that day, B-17s from Midway attacked the force, but scored no hits. Still, the Japanese were coming, and US searches could intensify.

At 0430, Admiral Nagumo Chuchi opened the Battle of Midway proper, launching a strike of over 100 aircraft against the airfield at Midway. An hour later, as the strike was finishing forming up, a PBY flew over the Japanese Striking Force, detecting a pair of carriers and the incoming airstrike. It dashed off a warning to Midway and a sighting report to the US carriers. Midway’s response was to launch an immediate attack, and scramble their fighters for defense. At the same time as the air strike left the Japanese fleet, Nagumo had his cruisers launch their scout planes, in case there was an American force around. There were really too few to do the job, and so they had massive search areas to cover. One plane took off half an hour late- and, unfortunately for the Japanese, it was this plane that would have to search the area where the US carriers lay.

These proved a disaster for the American force. At 0620, the Japanese strike reached Midway. A desperate air to air engagement drew in 28 American fighters- after a few minutes fighting, however, only two would be able to fly again. The Japanese strike inflicted heavy damage to the facilities on Midway- however, it failed to damage the runway or fuel supplies, meaning the airbase could still be operated. Meanwhile, at 0720, the planes that took off from Midway found the Japanese carriers. Of the 37 planes launched from Midway, 17 were shot down by Japanese fighters and anti-aircraft guns, while inflicting zero hits.

After this first exchange, Nagumo had to make a decision. His strike commander at Midway had reported in, and advised a second strike against Midway to destroy the air base. In accordance with Japanese Carrier doctrine, Nagumo hand held about half of his aircraft back from the strike. His torpedo bombers were armed with torpedoes, in case the American fleet just happened to be around, while his dive bombers were unarmed. This way, they could be easily loaded with armor piercing bombs for ships, or contact fused bombs for land attack. Against orders, he ordered the reserve armed with bombs for a second strike on Midway at 0720. However, at 0800, Tone’s scout plane reported the unexpected- US naval forces northeast of Midway. However, they made no report of what kind of ships, and it would take them another half hour to sight and report the existence of American carriers.

At this point, Nagumo’s subordinate, Yamaguchi Tamon, recommended launching an immediate strike against the carrier, no matter how the planes were armed or prepared, so the decks could be cleared before the Midway strike force arrived and needed to land. However, Nagumo believed- correctly- that because the Japanese carriers had been busy scrambling fighters to deal with aircraft from Midway, there would not be time to raise, spot and launch the strike before the Midway planes returned. So, Nagumo decided to rearm his reserve with torpedoes while the Midway strike landed. After recovering the Midway strike, he would launch the torpedo reserve as a strong strike against the carrier, and prepare the returning planes for another strike against Midway.

Meanwhile, the Americans had their own problems to solve. The sighting report put the Japanese carrier force just outside American aircraft range. Spruance began moving his carriers closer, and estimated that at 0700 his planes would just be in attack range, and he could launch. However, he did not communicate well with Fletcher, who would not be in position to launch a strike until 0800. Also, American carrier operations were not very effective- while the Japanese could clear 100 planes from four carriers in 7 minutes, it took two American carriers an hour to achieve the same feat. Rather than have his planes form up into a coordinated strike- which they couldn’t do because of the extreme range- he ordered each squadron to fly on as it formed up, and Fletcher did the same.

Once in the air, the problems were hardly over. The commander of one of Hornet’s groups flew the wrong heading , and just wandered around the North Pacific for a bit without sighting anything. Along the way, their fighter escort ran out of fuel and ditched. John Waldron, commanding the torpedo bombers in that group, decided his commander was an idiot, and flew the proper course. Waldron’s squadron sighted the Japanese fleet at 0920, and began their attack run. All of them were promptly shot down. At 0940, another 14 Devestators made an attack, and ten were lost- and the other four failed to score a hit.

The losses were not completely in vain. The Japanese fighters providing cover to the Japanese carriers had to dive down to low altitude to catch the torpedo bombers, and expended a great deal of fuel and ammo to shoot down the attackers. The carriers also had to maneuver violently to avoid potential attacks, and could not launch aircraft during the attack- and moving aircraft and arming them was nearly impossible as well.

At 1000, the last American torpedo squadron appeared, and began forming up for an attack. The remaining Japanese fighters pounced on them, taking 10 of the 12 planes that made the attack run. However, while all this was going on, Lt, Commander Wade McKlusky, commanding a force of Dauntless dive bombers, had sighted a Japanese destroyer. This destroyer had detached from the main carrier force to attack an American submarine, and the US planes followed it right back to the carriers, arriving at 1020- just as another group of dive bombers from Yorktown arrived.

The timing was perfect. Japanese fighter cover was still on the deck, dealing with the remains of torpedo attacks. Japanese gunners were searching the wavetops. The crews on the carriers were struggling to refuel and rearm ships, Fuel hoses were strung across decks, full of gasoline. Torpedoes and bombs were stacked around the hangar during the rearming process, waiting to be returned to the magazines.

At 1025, the American dive bombers began their attack. By 1030, Yamamoto’s plan for an expanded perimeter and a crushed US Pacific Fleet would be aflame. Three squadrons attacked three Japanese carriers. Five bombs hit Kaga, lighting her deck on fire from stem to stern. Soryu took three bomb hits, lighting planes waiting for launch aflame. Only one hit Akagi, but it hit her lowered elevator, allowing the force of the explosion to rush into the hangar deck, destroying planes fueled and armed for battle. The carriers, while heavily damaged, could have been saved, if Japanese damage control was not extraordinarily poor. Had they been American ships, Akagi and perhaps Soryu would have survived- but, the fires were far too much for Japanese damage control, and they would burn for the next day.

The Japanese wasted no time in launching a counter attack from the one remaining carrier, Hiryu. This strike found a returning American squadron, and followed it back to Yorktown. They attacked immediately, at 1200, scoring three bomb hits and leaving the Yorktown dead in the water. Believing they had sunk her, the Japanese strike reported one destroyed American carrier. However, American repair crews got to work, patching the flight deck and putting the engines back online within an hour. However, just as she was back in service, the second wave of the Japanese strike arrived at 1330, putting two torpedoes into the wounded carrier. There would be no recovering from this strike- Yorktown would be taken under tow, only to be finished off by submarine attack.

The Japanese commander on Hyriu, Yamaguchi, believed that he had put two of the three American carriers out of the fight, and now it was one on one, and a race to find each other and put together one last attack. Unbeknownst to him, it was a race he had lost. Scouts from Yorktown had detected Hyriu at 1330, and an American strike was enroute even as his planes finished off Yorktown, an at 1700, 24 divebombers swarmed down onto her. They scored five hits, and Hiryu caught on fire, which soon became uncontrollable. She burned well into the night.

However, because of his need to put his planes in range of the Japanese carriers, Spruance had opened himself up to a counterattack by Japanese surface ships. Without his carriers, Nagumo ordered his cruisers and destroyers towards the location of the American fleet, hoping to catch them at night. Yamamoto ordered another force to head for Midway to bombard the island, while he sent other ships racing to support Nagumo’s effort to bring the American carriers to battle. Because of the late returning strike on Hiryu, Spruance had to stay close to Japanese forces as the sun went down, and had to sprint hard to not get caught by a surface attack. Realizing he would not catch Spruance on the night of the 4/5th of June, Yamamoto retired.

The next day, the two sides searched for each other. Spruance looked for Nagumo and Yamamoto, while they looked for him, without much success. On the night of the 5/6th, a US submarine sighted the bombardment force headed for Midway. However, the submarine commander only sent a vague report, and Spruance hustled to attack this force in case it was Yamamoto’s battleships. However, during the 6th, his air crews found a force of cruisers and destroyers, which they pounded relentlessly, sinking one heavy cruiser and severely damaging another. Yamamoto decided to withdraw that day, and Spruance, out of fuel and low on planes, returned to Pearl Harbor.

The battle had extracted a heavy toll from Japan: four fleet carriers and a heavy cruiser, along with 248 aircraft and 3,000 men. The Americans had lost one carrier, 150 planes and 307 men. The Battle of Midway allowed the US Pacific Fleet to gain carrier parity with the Japanese fleet for the first time in the war- after the battle, both sides had two carriers capable of fighting, though Saratoga and Wasp would come into service later in the year to fight in the Solomons campaign. Those battles would stretch into 1943, and would be hard fought- but, I suppose that’s a story for another day.

If you liked this bit of history, feel free to comment below. If you’d like to read more military history here on 11W, please take a look at our archive: