Well, the championships are all in the books. It’s just a matter of time before we see who shows up in the playoffs- let’s hope the stars keep aligning for the good guys.

It was also just a matter of time before the Persians would come back to Greece. However, for a variety of reasons, it wouldn’t be Darius, but his son, Xerxes, who came to subjugate the Greeks. And while, ostensibly he came to deal with Athens, the first army- and fleet- he faced would be led by Sparta.

If you found this interesting, feel free to comment below. If you'd like to take a look at some of the battles that shaped this one, feel free to look at the archive by clicking here.

The Spartans

While the Athenians were a rising power in Greece by the early 400s, the Spartans had long stood as the leading Greek city, and had been since the 700s. In that time period, most Greek cities experienced rapid population growth as climatic conditions improved. Most Greek cities solved the tensions caused by this rapid growth by sending out colonial expeditions- this is how the Ionian Greek cities were founded, for example, along with other Greek cities we’ll see later.

The Spartans solved their population crisis with war They crossed the mountains to their west, and invaded the fertile valley held by the Messenians in the 740s or so. The war raged for 20 years, but, ended with the Messenians completely at the mercy of the Spartans. The Spartans inflicted a severe tribute on Messenia, effectively turning them into a vassal state of Sparta. The wealth that came into Sparta caused a great deal of strife and turmoil in Sparta, which led to them ignoring the Messenians, who grew stronger. This led to the Messenians revolting, with the support of Argos, one of Sparta’s rivals in Greece. While the Spartans put the revolt down, the turmoil of the war, and the threat of another revolt, led to major reforms in Sparta.

By traditions, these reforms were set down by Lycurgos, though, like just about everything about Sparta, (Including everything I just said) we’re just not sure if he existed, or if things happened the way the Spartans told others they happened. No matter what, the reforms sponsored by Lycurgos created the Spartan society that survived through the next few centuries, and entered into legend.

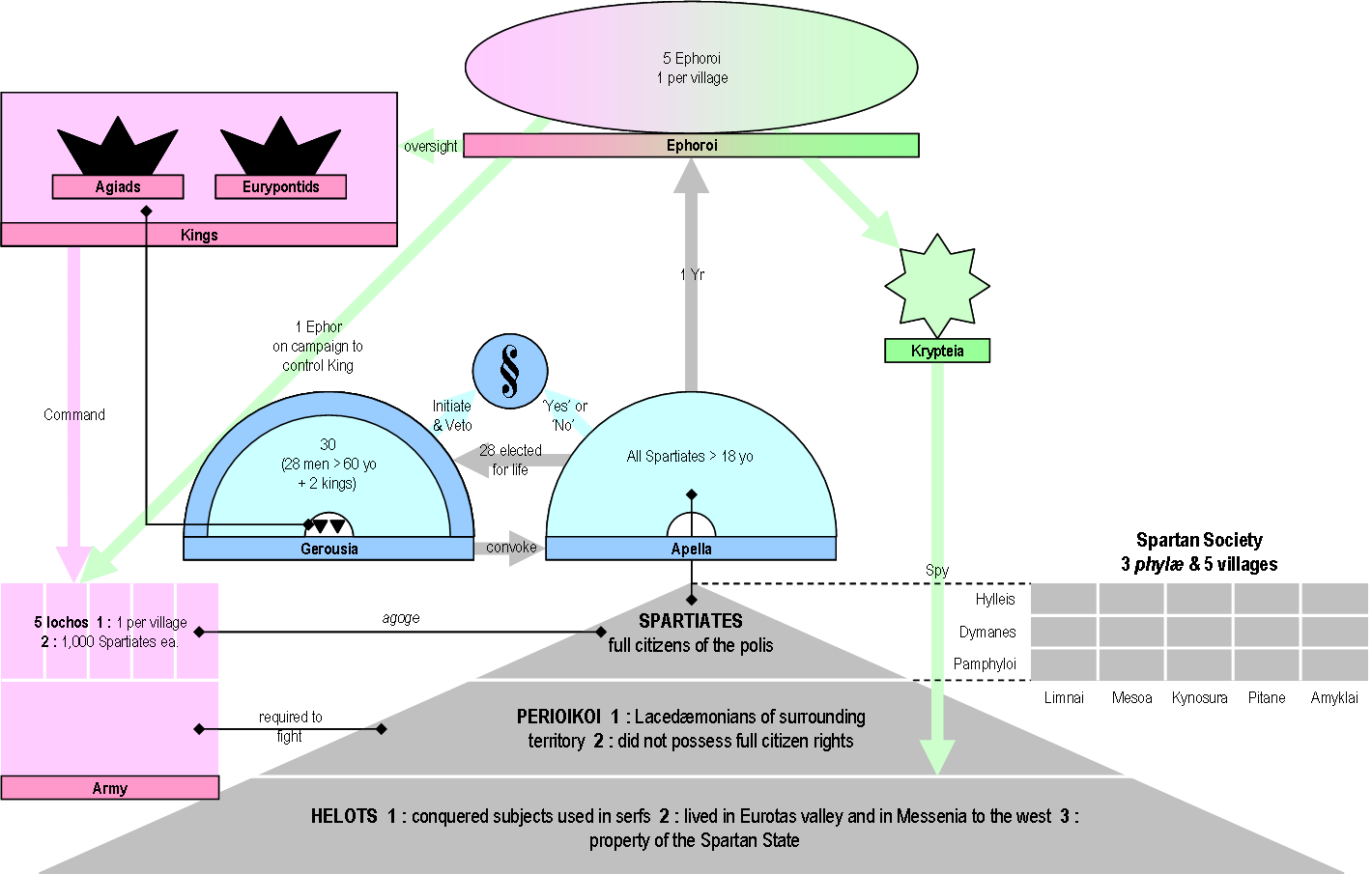

The focus of Lycurgos’ reforms were threefold: first, prevent a helot revolt, second, prevent internal strife in Sparta, and third, prevent a helot revolt. The first and third will end up being a running theme in Greek history. Lycurgos created three classes in Sparta: Spartiates, the full citizens of Sparta, the perioikoi, who were free non citizens who did much of the non-farming work in Sparta, and the helots, the descendants of the Messenians who became farming slaves owned by the Spartan state. He divided up the land and distributed it out equally to the Spartiates, along with helots to work the land. He then famously declared that the only acceptable profession for Spartans was the profession of arms, and set to create the agoge, a ten year training program for all Spartan men that started at the age of seven, and saw all boys taken from their families to be raised by the state to learn how to fight, and to be indoctrinated in Spartan culture.

Lycurgos also created a political system that, when combined with the indoctrination of the agoge and the communal mess halls, where all men ate together after graduating the agoge, reduced much of the outright political strife in Sparta- instead, it became something much more sublimated and hidden from history. He made the two royal families of Sparta co-equal, preventing conflict between them and guaranteeing that Sparta would always have at least one king, since only one of the two would be with the army at any given time. However, most of the power in the kingdom rested not with the kings, but with the five ephors, one from each of the five villages of Sparta, that held much of the day to day executive authority. While one of the kings would command the army, one of the ephors travelled with him to reign him in. The ephors were elected for one year by the Apella, the assembly of all Spartiates, and could only serve once. In addition to their executive duties, the ephors were also responsible for the krypteia, the group that kept the helots in line by arrest, executions, and the occasional war against unarmed helots. While the ephors held executive power, their short terms made it difficult for them to exert much legislative influence. That fell to the gerousia, a body of 30 men. 28 were men over the age of 60 elected by the Apella, while the other two were the kings. The Gerousia could convoke the Apella, and propose legislation and other issues to the Apella, who voted on them without debate.

Sparta’s fear of a helot revolt extended into their foreign policy. Given Argos’ support for the Messenians in their revolt in the 600s, the Spartans marked them as their main rival in the region. In the 550s, the Spartans sent troops to end a civil war in Corinth, evicting one of the factions in return for an alliance with the other. The Spartans supported the city of Elis in their bid to permanently host the Olympic Games, gaining another ally. Both Elis and Corinth were the leading cities in their area, leaving only Argos and Tegea opposing Spartan rule over the Peloponnesus.

Sparta settled accounts with Argos in 546. That year, the Argives and Spartans agreed to the Battle of the Champions, where 300 men from each side would fight to settle control of a disputed land. The last man, or men, standing, would claim victory. By the end of the fight, there were two Argives standing, who believed they had killed all the Spartans, so they left. However, one of the Spartans was only wounded, and he stood up later, building a victory trophy for the Spartans. The Spartans claimed they won, since they held the field, while the Argives claimed victory, since two of their men lived, against one Spartan. This dispute spilled over into all out war, where the Argives fought against the combined forces of Sparta, Elis and Corinth. This ended poorly for Argos, with their army crushed and their land devastated, ending them as a threat against Sparta for the time. With that settled, the Spartans moved on Tegea in 530, defeating them in a series of battles. However, rather than enslave the Tegeans, they forced them into an alliance.

This alliance- between Sparta, Corinth, Elis, Tegea and all the other cities in the Peloponnesus other than Argos, became known as the Peloponnesian League. The League was a largely defensive alliance, where the cities agreed to come to each other’s aid in wars they didn’t start, and to bring armies to fight alongside the Spartans in case of a helot revolt. This was a winning deal all around- the Spartans got manpower for fighting the helots when needed, while the other cities could rely on each other and the mighty Spartan army for their own defense. The Spartans largely controlled the alliance- all disputes in the alliance were settled by a council. However, Sparta’s vote counted for 50% of the council’s votes- Sparta plus one other town or city set league policy.

In 490, when the Spartans rejected Darius’ demand for submission, the rest of the League followed suit, and prepared for war with Persia. When the Peloponnesian League allied with Athens, the alliance became known as the Hellenic League, with the Spartans largely in charge of the war.

Meanwhile, in Athens and Persia…

The Athenians took their victory at Marathon as fundamentally decisive. They quickly turned their attention to fighting local wars to follow up their great victory. In one of these wars, Militiades, the victor of Athens, was mortally wounded. Into the void stepped two factions: the wealthier hoplites, led by Aristides, and the poorer hoplites, led by Themistocles. Political strife between the two went on for several years, and came to a head in 483-82. In 483, a new seam of silver was discovered in the Laraum mines near Athens, and debate grew about what to do about it. Aristides supported giving the silver to the hoplites of all stripes, in order for them to buy more and better armor to prepare for war in Greece and, perhaps, against the Persians if they decided to come. Themistocles argued that the money should be used for ships, both for use against local Greek rivals and, of course, the Persians. Strife between the two factions grew intense, and the assembly in Athens voted to hold an ostracism- an election where the man who got the most votes had to leave Athens for ten years. In reality, it was a referendum on the two plans to spend the silver. After the votes were counted, Aristides had the most votes, so he left the city and Themistocles took over sole leadership in the city. He began funding hundreds of ships.

Meanwhile, in Persia, the defeat of the Persian army at Marathon prompted a rebellion by the satrap of Egypt. Egypt, with its large population that refused to accept Zoroastrianism as a legitimate religion, loyalty to its satrap- whom most of the population viewed as a king- and large population and wealth supported by the Nile River, was prone to trouble. It had been one of the kingdoms that rebelled against Darius’ coup, and the defeat at Marathon spurred another rebellion against Persia. Darius had to abandon his plans for a followup campaign in Greece to march on Egypt. The campaign exacerbated his failing health, and, in 486 he died, leaving the throne to his son, Xerxes.

Xerxes faced another rebellion in Egypt, followed by a series of revolts in Babylon in the mid 480s. It wasn’t until 482 that his reign was particularly secure, and he could turn his attention to Greece once again. He ordered a complete mobilization of the Persian Empire- he hoarded enough silver for the campaign that the economy of Persia suffered from a currency shortage. He called hundreds of thousands of men across the Empire into the army- Herodotus claims over a million, even skeptical scholars place the size of his army at nearly 250,000 men- almost as many men as fought on both sides combined at the Battle of Wagram 2300 years later! His army was a mix of all sorts of troops. The Persians simply demanded men armed in the local style, so the Persians had light infantry, archers, heavy infantry, cavalry of all sorts, skirmishers, line troops- enough men to fill the field and eclipse the sun with volleys of arrows. He also built a fleet of 1300 triremes and 3000 supply ships to move the food needed to feed the army, and another 40,000 or so marines.

It would be, most likely, the largest army ever assembled until the 1800s- certainly in Europe, perhaps in the world. (Some Chinese armies might have been bigger, and the Romans would, several times, support more men under arms, but never in a unified army.)

Of course, moving such an army would not be a simple feat, and its sheer size rather dictated the campaign for the Persians. It would not be possible to move that many men by sea and repeat the Marathon campaign, so the army would have to march out of Lydia, cross the Hellespont, move through Thrace and then down the coastal mountain pass of Thermopylae into Attica, then across the Isthmus of Corinth into the Peloponnesus, and through the Gate at Tegea into Laconia. It was a long way to walk, and the army could not possibly feed itself in Greece. The 3000 cargo ships would have to shuttle food from magazines in Persia over to Greece to sustain the army.

This meant a few things for the Greeks fighting the Persians. First, they could not assemble anything like the size of the Persian Army. The Spartans could muster perhaps 10,000 men without arming the helots (Which they would eventually do, adding another 40,000 men to their army), and the rest of the Peloponnesian League could muster perhaps another 25,000. Athens had about 9,000 men under arms, with 10,000 more coming from smaller Greek cities who agreed to fight the Persians. They could muster maybe 400 triremes, about half Athenian, another 150 from the Peloponnesian League, and 50 from smaller cities. This meant that the Greeks would have to fight the Persians where the weight of numbers could not tell. Themistocles argued that the Greeks should make their stand at Thermopylae, where the army could fight on narrow terrain, and the arrangement of islands made it possible to isolate parts of the Persian fleet, and a well led Greek force could prevent the Persians from outflanking the army at sea.

The Spartans were largely resistant to this strategy. First, Thermopylae was rather far from Sparta, and if the army was that far away, and perhaps suffering defeat, the helots might well revolt. It also pulled the armies of the Peloponnesian League away from their homes, which made it most likely those men would not fight particularly hard to save Athens while their homes were under threat. The Spartans, therefore, wanted to fight at Corinth, where the land narrowed again. The Athenians, of course, opposed this- since it meant sacrificing Athens to save Sparta.

In the end, events began forcing the Spartan hand. Unsure about what to do, the Spartans consulted the Oracle at Delphi, to see what the gods suggested. They were told, “Either a King of Sparta dies, or Sparta burns.” As the Persian army approached in the summer of 480, they approached during the Olympic Peace- the Spartans, as pious as they were, refused to fight with their whole army. However, if they did not act, the Athenians might well defect without a fight. So, the Spartans compromised. They sent a force of 300 champions, under their elderly king, Leonidas, to Thermopylae. Several thousand Greeks joined them at the pass, while their seaward flank would be secured by 290 Greek ships, commanded, de facto, by Themistocles.

The Battles of Thermopylae and Artemiseum.

Since the geography can be a little confusing, we’ll start with a map.

In either early August or September of 480, the Greek army made it to Thermopylae, where they assumed control of a wall built earlier by the Phocians to control the pass. The wall wasn’t tall enough to serve as a real fortification, but would give the Greeks a place of refuge. It overlooked one of the wider parts of the pass, where the Greeks could deploy their troops in roughly equal numbers to the Persians. As units fought in the pass, both sides would be able to rotate troops in an out from their refuges on the sides of the pass. Meanwhile, the Greek fleet took up a position at Artemiseum, where the island of Euboea makes a strait with mainland Greece. Here, the Greeks could avoid being outflanked by larger Persian numbers, and prevent an amphibious landing behind the pass.

Four days before the battle began, the Persian army began to arrive at the pass. Seeing it blocked by Greeks, Xerxes sent diplomats to negotiate passage for his army. He offered the Spartans peace right on the spot.

Leonidas refused.

Xerxes offered to make the Spartans the hegemons of Greece, if they let the Persians sack Athens.

Leonidas refused.

Xerxes told the Greeks to lay down their weapons, to go in peace, and he would spare their lives.

Leonidas told him to come and take his weapons.

Xerxes, however, did not attack immediately. He sent his fleet around to Euboea, with plans to load up some of his men, sail down the Gulf of Euboea behind the pass, and take the Greeks from the rear. However, the day after his army arrived at Thermopylae, a storm came up which raged for two days. This storm cost the Persians 400 ships, wrecked along the coast, while the Greeks rode it out just fine. When the Persian fleet reached Artemisium, they found it blocked by the Greeks, and sent word to Xerxes.

He ordered a general attack the next day- both at the Greeks in the pass, and the Greeks at sea.

At Thermopylae, the Persians sent forward a force of 10,000 men in a frontal assault, supported by an equal number of archers. However, the archers fired from more than 100 yards away, and their arrows were too spent to penetrate Greek armor and shields. When the Persian assault closed, their armor was too light, and their weapons too short, to effectively fight the Greeks. The Greeks, because of the narrow nature of the pass, could fight in dense formations and rotate their men. This way, they drove off several attacks in the morning, until the Persians stopped to regroup at about noon. In the afternoon, Xerxes ordered an assault with the 10,000 Immortals, the elite heavy infantry of the Persian Empire, but the Greeks threw them back, too. Hundreds, if not thousands, of Persians lay dead, with only a few dozen Greeks to show for it.

Meanwhile, the Persian fleet, diminished by the storm, moved to attack the Greek ships. Part of the Persian fleet- about 200 ships- tried to sail around Euboea to outflank the Greeks, but ran into another storm and was lost. The Greeks, however, were still in a pickle- the were out numbers 2 to 1, at least, while their crews were ill trained and lacked sea experience. Meanwhile, the Persians not only had more ships, but better crews and ships that handled better. In order to counter this advantage, the Greeks formed a crescent formation, with the concave side of the formation facing away from the Persians. This prevented the Persians from using their superior maneuverability to isolate Greek ships. The Greeks also loaded up with marines to board Persian ships, since they couldn’t maneuver well anyway.

The Persians sailed against this crescent formation cautiously. This allowed the Greeks to, at a prearranged signal, spring out quickly and surprise the leading Persian ships. They came alongside the Persians, storming ships quickly and taking about 30 before the Persians decided to call it a day, and retreated out towards open water, where the Greeks couldn’t follow.

On the second day, Xerxes ordered renewed attacks against the Greeks- given the fierceness of the fighting, he figured, there couldn’t be too many of them left. However, the Greeks weren’t really exhausted at all, and the Persian attacks suffered the same fate as the previous day- not particularly affected by even clouds of arrows, and able to overwhelm the Persian infantry in close quarters. Meanwhile at sea, the Persians decided to lick their wounds, and not attack.

While the Greeks looked rather pretty after two days, their luck would change quickly. A Greek traitor, Ephilates, informed the Persians that a narrow pass allowed a small force to get around Thermopylae, and Xerxes jumped on it. He sent a small force- about three times the size of the Greek army- to surmount the pass, then take the Greeks in the rear. Meanwhile, at sea, the Persians formed a massive, repaired fleet and closed on the Greeks en masse.

When word came that the Persians were marching on his rear, Leonidas decided to send the bulk of his army home- there was no way to survive a double envelopment. However, he ordered the Spartans to stay behind to act as a rear guard to let the rest of the Greeks get away. The 700 Thespians present, along with 400 Theban exiles who refused to ally with the Persians, also stayed to make a suicidal last stand. The Persians surrounded this rearguard, hemming it in with infantry before bringing up archers at close range to smother the Greeks with arrows. Eventually, the Greek formation fell apart, and the Persian infantry moved in for the kill. However, the last stand forced the Persians to take a few days to clear the pass and reorganize, letting more than 3,000 Greeks escape the battle.

Meanwhile, at sea, the Persian fleet approached the Greek fleet, matching the Greek crescent formation with their own. They held tight, and closed in on the Greeks, leading to a rather well organized melee in the strait. The two fleets basically traded ship for ship, each losing about 100 ships. The Persians could afford 100 ships lost, but the Greeks could not. Once word came that the Persians held Thermopylae, Themistocles retreated back to Athens.

At the end of the day, about 2,000 Greeks lay dead at the pass, with perhaps as many as 20,000 Persians dead. 100 Greek ships were lost in action, compared to about 200 Persian ships. It was a costly victory for the Persians- but the route to Athens was open, and no army stood in the way.

While the Greeks had lost the battles, the war was well on. The Hellenic Alliance had survived its first battle, and the Spartans had shown a willingness to fight for someone other than themselves. The legend of Thermopylae would survive through the ages if the Greeks could pull off one more miracle like the one at Marathon….