The difference a single elite player can have

The difference a single elite player can haveLast week I introduced what I called a power cycle theory of college football, which was based upon a theory of international relations that explains the connection between country growth, decline, and international conflict.

Power cycle theory is based on the idea that countries undergo cycles of power (or nonlinear patterns of change) that affect their foreign policies and their propensity for internation war. College football teams similarly undergo cycles of growth and decline, especially for the traditional great powers - Texas, Florida, Ohio State, USC, Michigan, etc.

However, the analogy between power cycle theory and college football breaks down in the details. While power cycle theory argues that countries will eventually experience decelerating growth and eventually reach a peak relative power level, there's no theoretical reason why a college football team couldn't win every game each year ad infinitum.

Yet we can again use the fundamental insights from the theory to help analyze growth and decline in college football. While programs could experience that kind of sustained dominance, we have yet to see it - even the very best teams suffer bad seasons.

Football commentators and fans often painfully repeat the aphorism that these "great powers of college football don't rebuild, they reload." While that's true to some extent - some powers rarely have even mediocre seasons - we generally observe teams go through periods of success followerd by varying lengths of mediocrity (or worse).

College football theory (no that's not a thing, but it should be) lacks a theory of how programs rebuild (reload, whatever) or simply build in the first place. Besides looking on a case by case basis, it's important to have a generalizable theory of how programs like Michigan can go through a slump like they did from 2008-2010 and then seemingly recover in 2011. Is each team's experience unique or are there some commonalities when programs rise?

There are plenty of traditional football powers in various stages of the power trough - Texas, Ohio State, Florida come to mind - that would love to know how to get back to their winning ways.

To get a handle on this question I examine the rise and fall of the top teams in the B1G over the last decade. While the time window is fairly small, it is large enough to examine the power transitions between the top teams in the Big Ten.

generating the POWER CURVES

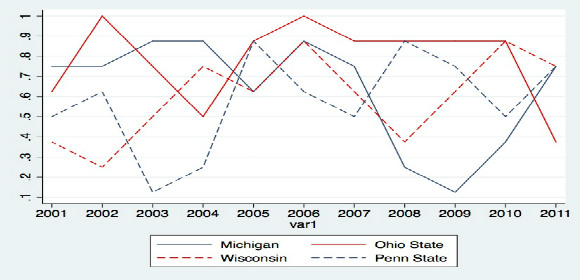

There is basic agreement that Ohio State, Michigan, Penn State, and Wisconsin are the class of the Big Ten and that everyone else is a notch or two below (or three if you're Indiana). This is supported by the fact that these four have won or co-won ten of the last eleven conference championships. The B1G's hierarchy has been relatively constant, save for Michigan State's rise over the past two years.

I then computed these four teams' winning percentages for conference games. I used conference games instead of overall record for a few reasons: 1. In order to test power cycle theory properly, I needed a measure of relative, rather than absolute power. Because there is a finite number of games in the conference schedule (8), and each win necessitates a loss from one of the other teams, it more closely approximates a measure of relative power. 2. Conference schedules are more or less consistent each year, so strength of schedule is held more or less constant.

Power cycles

A couple of things are readily apparent when looking at the rise and fall of the big four's conference winning percenatages: Ohio State is consistently at the top of the Big Ten, with Michigan close by (except for the Rich Rod years). Ohio State also has the least amount of variation. As Abe Froman asked last week, there are some commonalities between the programs over time, but Ohio State has far less variation than any other program. Wisconsin and Penn State are especially prone to multiple "rebuilding" years in a row, while Ohio State typically has one every three to five years.

Ohio State's B1G dominance is plain to see

Ohio State's B1G dominance is plain to seeIt's much harder to generalize about Michigan under Rich Rod, as the program took such a severe hit in conference winning percentage.

Ohio State had two peaks (2002 and 2006) and two troughs (2004 and 2011); Michigan had four peaks and three troughs; Wisconsin three peaks and two troughs; Penn State had three peaks and four troughs over the last decade. Just the number of peaks and troughs alone indicates a program's stability, and Ohio State dominates in that regard.

Also notable is Ohio State from 2005 to 2010: sheer dominance, with the conference winning percentage never dipping below .875.

How powers rise in the b1G

There are five instances of extreme rises in the past decade: Penn State from 2003-2005, Michigan from 2009-2011, Ohio State from 2004-2005, Wisconsin from 2003-2005, and Wisconsin from 2008-2010.

There are some commonalities to each rise, which together might form the beginnings of a theory of how programs (in the Big Ten at least) rise.

1. Win the last few games of the previous year: 2002-2004 were known as "The Dark Years" in Penn State football, and for good reason - they went 3-9 and 4-7 in '03 and '04. However, the 2004 team finished the season with rare wins over Indiana and Michigan State, which turned out to be harbingers of the excellent 2005 team, which went 11-1.

This trend applies to most of the other programs on the rise. For instance, the 2004 Buckeyes lost 3 straight in conference play only to end the year with improbable victories over #7 Michigan and Oklahoma State in the Alamo Bowl. Winning at the end of the season generally means good things for the next season.

2. Get a new head coach: Save for Penn State (which had Paterno for the whole period) and Michigan (which had Rich Rod and Gred Robinson), teams generally see improvement within two years of hiring a new head coach. A corllary for this rule is that if you're going to do well at all under a new head coach, you'll know by his second year. See: Nick Saban, Gene Chizik, Jim Tressel, Urban Meyer... the list goes on.

Wisconsin in 2006, Ohio State in 2002, and Michigan in 2011 all had brilliant seasons under first or second year head coaches. This is because new head coaches can serve as a wake up call, changing not just the offensive or defensive styles and coaching staff, but also the culture of a program.

3. Base your offense around a young hotshot: Wisconsin had PJ Hill in 2006 and John Clay in 2008-2009, Ohio State had Maurice Clarett in 2002 and Troy Smith in 2005-2006. The difference a single offensive player can is incredible, especially at quarterback or running back.

Even a single player can instill an offense with the ability to pick up consistent first downs. All of the players listed would go on to collect multiple awards and records during their careers.

In summary, build some momentum the previous year, hire a new head coach if need be, and work to sign even one special offensive player. Next week we'll take a look at the flip side - how to avoid multiple rebuilding years in the Big Ten.